This new policy brief, which synthesizes research from the Haas Institute Diversity and Democracy affiliated faculty, lifts up lessons from recent research on how to confront voter disaffection, support inclusive identities, and increase democratic participation among underrepresented groups. The brief argues that many conventions of polling, categorizing, and engaging voters in campaign outreach reinforce chronic disparities in US election turnout—disparities that are particularly stark in midterm years like 2018. If we are to work toward a voting electorate that more closely mirrors the country’s diverse citizenry, we must confront the ways the information we do or don’t collect—and the outreach we do or don’t fund—contributes to a cycle of exclusion and non-participation.

Titled “Realizing a More Inclusive Electorate: Identity, Knowledge, Mobilization,” this brief draws together salient findings from scholarship by the Diversity and Democracy cluster at UC Berkeley. It makes a series of evidence-based recommendations on how researchers, pollsters, political donors, and public officials can make their work supportive of broader and more inclusive civic participation.

In particular, the brief encourages donors and philanthropists to invest in democracy itself by supporting organizations that carry out year-round civic engagement, leadership development, and capacity building in communities and demographic groups that partisan campaigns often pass over—most notably young people age 18-29, and many communities of color. It also summarizes important new research on public distrust of media, and its relationship to declining support for democracy and increasing hostility toward religious, national, and racial "others."

Download a PDF of this brief here.

Introduction

THE UNITED STATES has grown steadily more diverse over the past decades in terms of the racial, ethnic, religious, and other identities of its citizens. To an extent, this diversity has been reflected in the composition the electorate—the total of eligible voters who cast ballots in an election. However, the latter has not nearly kept pace with the former.

In fact, in some election cycles, non-white race/ ethnicity groups actually lose ground as a share of the vote, even as they grow as a share of eligible voters.1 More broadly, it is the norm that in our representative democracy just three in five adult citizens participate; a year with two-thirds voter turnout is exceptional.

We should not be content to explain either this overall non-participation or its uneven distribution across voter sub-groups as the product of purely individual choices. A wealth of scholarship suggests instead that numerous structures and processes directly contribute to low and differential turnout. This scholarship further offers insights into how to mitigate these problems to foster broader and more inclusive voter participation.

The Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society is engaged in research and policy analysis around elections in the interest of advancing democratic principles and practices in an increasingly diverse society. We are committed to a vision of civic and political life in which all individuals and groups belong, and all participate. Our vision of belonging requires a balance: On one hand, it should never be premised on same-ness, but instead affirms a range of personal and communal identities. On the other, it strives for a broad, inclusive “we” that can push back and inoculate against the distortion of difference into othering.2 An inclusive electorate further entails that everyone enjoy equal access to representation and opportunities to meaningfully influence democratic decision-making.

The purpose of this brief is to draw together salient lessons from research by Haas Institute faculty cluster members that can move us closer to these goals. Cutting across those lessons are common themes of identity, knowledge, and mobilization—and myriad relationships between and among them. We highlight in particular research that speaks to developments in the post-2016 socio-political context, with the brief both describing findings, and exploring them for their current implications. Because most of this research actually predates the 2016 elections, we can see that it is timely without being “timebound.” That is, its lessons are current to the present moment, but should also be kept close at hand as we advance in the enduring work of realizing a truly inclusive democracy.

Knowledge Production Intervenes in the Electorate

RECENT RESEARCH by faculty cluster members demands that we consider the ways in which knowledge produced about elections and voters can itself influence voting behavior. That is, we should recognize enterprises such as election polling, forecasting, and analysis not merely as representations of the electorate, but also as interventions in it. As these forms of knowledge circulate, they shape the way voters understand their own political concerns, efficacy, and community. This can push them not only to one candidate or party over another, but also away from electoral participation altogether.

Opinion Polling

Faculty cluster member Taeku Lee has been a leader in critical research on the influence of polling on political participation and representation. In his book Mobilizing Public Opinion, he recounts the history of social surveys’ rise in the 1930s, and their transformation of the public understanding of “public opinion.” This history is one of a shift from “public opinion” conceived as an abstract and speculative matter to one subject to the authority of scientific inquiry and reducible to a grid of survey data.3

The result, Lee argues, is that pollsters and survey research centers have an undue say in determining what count as significant—and even legitimate—issues of public opinion and debate. Lee carefully makes the case that polling can propagate norms of mass opinion that limit citizens’ political imaginations of what can and should be. In presenting themselves as “mirrors of society,” opinion surveys in turn delegitimize those claims (and claimants) that lie outside those norms— contributing to their marginalization, alienation, and exclusion.

Furthermore, these marginalizing effects are distributed unevenly across socio-demographic groups. Lee points out that polls focused on the voting electorate—or what pollsters would call “high-propensity voters”—create representations of public opinion that are biased along lines of race and gender.4 So rather than a passive “mirror,” opinion polling mediates how—and indeed whether— constituents can locate themselves in electoral politics. It is an intervening institution with excessive power, argues Lee, to direct as well as disaffect democratic participation.

If opinion polling constitutes a story about what and who are politically consequential through what it asks and whose views it pursues, post-2016 surveys have done a disservice to the effort to realize a more inclusive electorate. Though overall participation was up slightly in 2016, millions who voted in 2012 did not cast ballots, along with tens of millions more eligible voters. Yet despite innumerable studies and profile pieces on Trump voters, we know remarkably little about these non-voters. Too often this group is cast ipso facto as “disengaged”—a gloss that rationalizes excluding them and their perspectives. When polling fails to examine those who did not vote, it conveys that they need not be treated as factors in future campaign strategies. In this way, its intervention is to create bases for their continuing disenfranchisement.

In Lee’s view, the undue influence of polling in politics is best countered by a reinvigoration of the public sphere. Central to this is renewing civic debate and discussion among well-informed citizens—what Lee considers the true marker of “public opinion.”5 Experimental field studies have shown that, when given opportunities to deliberate in small groups across moderate ideological differences, individuals can indeed reconcile their views and construct richer, socially legitimate expressions of public opinion.6 Widely shared “disagreement-curiosity” and openness to persuasion among the studies’ subjects are welcome findings for those looking to turn back the partisan polarization and animus prevalent in the US today. Yet that goal will undoubtedly require sustained commitments across sectors, including research, civil society, philanthropy, and government. The final section of this brief—on political discourse, deception, and distrust—offers some insights into the obstacles to reaching it.

Demographic Categories

Much of how politicians, analysts, and everyday citizens alike think about voter groups is organized around a grid of demographic categories, with race/ ethnicity (and often gender) at the center. These categories tend to dominate how election results are narrativized, as was certainly the case for the 2016 presidential election.7 On one hand, this is logical. Beyond their general social import, some familiar socio-demographic categories have in recent years become incredibly strong predictors of partisan voting.

Yet there is also reason for researchers, strategists, and funders to practice discretion about how they reinforce these categories. The work of faculty cluster member G. Cristina Mora is instructive. Mora’s research reminds us that demographic categories are neither inevitable nor passive reflections of social reality; rather, they are contingent constructs that hold significant sway in the formation of identities.8 Combining historical and social-science methods, Mora denaturalizes a group category that is today taken for granted in most understandings of US diversity: Hispanic. Mora shows how the panethnic “Hispanic” identity came together through a dynamic interaction among activists and advocates, government officials, and mass media. Despite that these actors were not motivated by a shared purpose, their common promotion and repetition of the term ensured the rise of Hispanic as a social fact.

As Mora further demonstrates, nor even did these actors have a shared definition of “Hispanic.” But in this ambiguity, she explains, was a key to the category’s success. The relatively fluid boundaries around the meaning of “Hispanic” allowed for different actors to invest the category with different interpretations, and thereby facilitated broader Hispanic identification. The patterns of its uptake also influenced what it would come to mean, showing how subjective identities and schemas for classifying people shape one another reciprocally.9

Mora’s analysis of “the making of Hispanics” is germane to the current political moment in light of the rise of a similarly ambiguous and inconsistently defined category: the white working class. This term— together with its initialism, “WWC”—is not entirely new of course, but its prevalence has increased dramatically over the past two years. Since at least March 2016, when Trump settled in as the GOP frontrunner, there has been a burgeoning cottage industry of polling, focus groups, and other studies producing knowledge on this nominal group. Knowing what we do about the role of such knowledge in forming social identities, researchers and funders should ask whether their investigations are actually propping up and intensifying the salience of the category they study. It is unlikely that this is the intent behind the considerable financial resources that have bolstered the “WWC” knowledge industry, but Mora’s account reminds us that their motivations may not matter to the outcome.

Knowledge that reinforces the idea of a discrete “white working class” threatens the building of an inclusive electorate for two reasons. The first is that it is fundamentally anchored in the construct of whiteness. As I have noted elsewhere, analyses of “the white working class” in the context of the 2016 elections vacillate between using income, educational attainment, non-urban residence, and myriad cultural factors as proxies for the amorphous notion of “class.”10 The common denominator is white identification; absent it, there would be no cogent identity of which to speak.

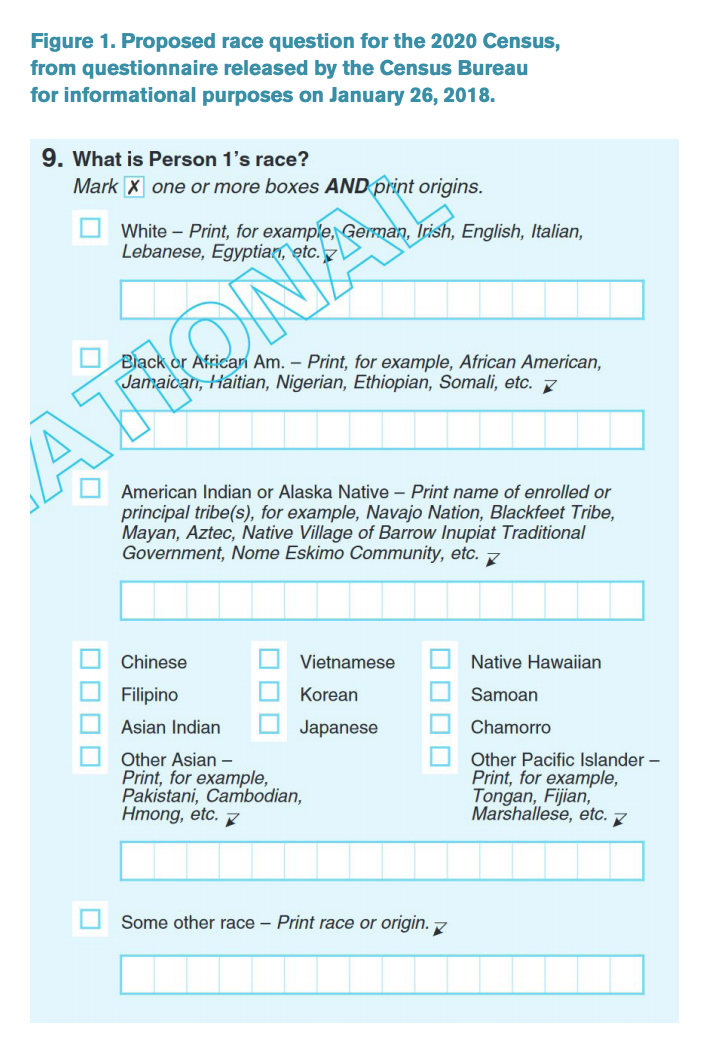

Historical and social research tell us that not all ethnoracial identities are exclusionary, but whiteness tends to be. Faculty cluster member Chris Zepeda-Millán and colleagues demonstrate, for example, that political mobilization around the Latino group identity increases participants’ sense of commonality with other marginalized groups.11 Meanwhile, recent findings from Taeku Lee and colleagues in the Voter Study Group show that strong in-group white identification closely correlates, among other things, with descentbased and religiously and linguistically exclusionary ideas about what it means to be American.12 For this and other reasons, researchers should pay close attention to the impact of changes to the question about race on the 2020 US Census. In its new formulation, the question will introduce a write-in area for white-identifying respondents to further specify their identities (see Figure 1). Unlike other changes proposed for the 2020 Census, this addition will appear without having been extensively field tested, and its purpose and effects are unknown.13

The second threat posed by knowledge that strengthens white working-class identification lies in the identity’s current articulation with far-right ethnonationalism. It is up for debate whether the interests of those represented as “the WWC” are served by mass deportation, corporate tax cuts, slashed social spending, and tariffs. But what is certain is that the WWC knowledge industry—birthed in response to Trump’s rise—feeds the narrative that “the white working class” has a linked fate with Trump, and that “it” is a natural constituency for his nativism. It also potentially offers in “WWC” a social positioning from which fringe actors and ideas can consolidate, and be launched into the mainstream, under the cover of a venerable label. This, in fact, is already happening.14

Forecasting the Electorate

Finally, based on her expertise in category construction, Mora has also had an important voice in scholarly debates on predicting the future composition of the electorate. More specifically, these debates concern how to forecast the share of the country, or the voting-eligible population, that will identify as something other than “white” by a given year. Such forecasts rely on Census Bureau data, and turn largely on models for estimating the number of persons born to one parent who is non-Hispanic white and another who is not.

Mora and her co-author Michael Rodríguez-Muñiz remind us that such (future) persons’ selfidentification patterns are not inevitable.15 Even more than other types of ethno-racial quantification, forecasts rest on fraught debates about how to assign who to which category.16 Given this, Mora and Rodríguez-Muñiz argue that we must recognize ethno-racial forecasts as themselves political and social interventions. That is, their projections into the future are tools of politics in the present. Among other things, by treating ethno-racial identities as inherited, forecasting inaccurately depicts these identities as given, timeless, and existing outside of experiences of injustice and political consciousness.17 Such a misrepresentation can end up feeding nativism and other exclusionary, “us-and-them” essentialisms. Over-emphasis on identity as inherited can also complicate solidarity efforts crucial to bridging difference for a broader, inclusive civic identity.

Empowering Communities by Improving Voter Engagement Practices

A NUMBER OF Haas Institute faculty cluster members have carried out empirical studies investigating how best to activate and mobilize voters of color, especially in lower-income communities. This research is particularly relevant in 2018—a midterm election year. Midterm contests consistently see large decreases in voter participation relative to the previous presidential elections, with drop-off rates sharpest among the young and communities of color. That is, the latter voter groups begin with somewhat lower presidential-year turnout rates than older voters and whites (overall), and then a smaller share remain in the midterm electorates (see Figures 2 and 3).

Some of these discrepancies in participation rates were evident in 2016, even if not always in the ways they were portrayed in the weeks after the election.18 For communities of color, some of the decline that year was no doubt due to the historically unpopular presidential candidates nominated by both major political parties. Also playing a role were new voter suppression laws and other exclusionary voting structures that disproportionately affect African American, Latino, young, and poor voters.19

But in 2016 and midterm years alike, we must also recognize in these uneven turnout drops a major failing on the part of political parties, campaigns, and voter-targeting operations. Here the research of some Haas Institute cluster members offers critical insights for re-activating “drop-off voters” and strengthening communities of color as constituencies that can hold candidates accountable, and thus feel that their participation does indeed matter.

Faculty cluster member Lisa García Bedolla has been at the forefront of research on civic-engagement outreach to voters of color for more than a decade. Between 2006 and 2008, she and collaborator Melissa Michelson were involved in 286 voter mobilization experiments in communities of color in California, from which they draw numerous lessons.

Mobilization to Activate Civic Identities and Participation

Overall, García Bedolla and Michelson’s work supports a model of voter engagement grounded in the establishment of meaningful relationships between outreach campaigns and targeted voters. Such a “relational” approach to Get-Out-the-Vote (GOTV) mobilization aims to meet citizens where they are, and engage them on basis of their own lived experiences, concerns, and priorities. Outreach should begin not with a staid “pitch,” but with a commitment to listening. Organizers place the focus on the prospective voter, working to draw out insights into her everyday life and what is most important to her. From there, messages about civic engagement may be framed in terms of constituents’ concerns, and a genuine exchange can ensue.20

More specifically, García Bedolla and Michelson develop a model emphasizing the importance of focusing on individual civic identity in GOTV initiatives.21 Due to myriad historical and structural conditions, many voters of color have difficulty experiencing themselves as the type of person who “counts,” and thus should be engaged, in civic and political action.22 Based on their research, García Bedolla and Michelson argue that successful voter outreach conversations are those that engage and help reformulate citizens’ personal civic selfunderstandings. That is, the canvasser should access the potential voter’s senses of political efficacy and civic duty, and work to lead her to a new cognitive orientation toward voting.23 This approach contrasts dramatically with the scripted calls, mailers, and media spots that continue to claim large shares of the funding devoted to voter outreach.

García Bedolla and Michelson’s field experiments also yield a number of other practical lessons about maximizing the impact of relational voter outreach efforts. They find evidence that GOTV is more effective when multiple contacts are made between organizers and potential voters, and spanning a longer period of time than the weeks immediately preceding an election. Who does the canvassing also makes a difference. That is, the messenger often matters as much as the message.24 García Bedolla and Michelson find that civic engagement increases more when campaigns identify, train, and empower local people to canvass, as opposed to bringing in experienced outsiders. It is also significant to employ canvassers who can address immigrant voters in their first language, a practice that affirms—through signaling—the voter’s inclusion in civic life and the electorate. Such signals are especially necessary in periods like the present in which frequent implicit and explicit messages aim to discourage and exclude certain groups from civic participation.

Mobilization to Build Community Capacity

Getting voters involved in one campaign or election cycle is not the same as building the electorate, of course. In fact, a GOTV initiative that is successful in getting people to the polls can end up being counterproductive if it does not leave behind any capacity or sustainable structures for future political participation. For this reason, it is significant to note that recent scholarship on face-to-face campaigns and relational organizing also highlights the longer-term benefits of these approaches in target communities.

A major longer-term dividend of campaign approaches like those García Bedolla and Michelson study is the capacity vested in local individuals who participate in canvassing. On one hand, this capacity comes from the training and experience community members receive. Learning to listen to constituents and steer people with very different interest levels and attitudes toward civic engagement are valuable skills for local political power-building. They are “social capital” that stays in the community, outliving any particular campaign.

But beyond tangible training and skills, local canvassing initiatives also build capacity by increasing the political agency and commitments of canvassers. Going door to door for a campaign requires courage and confidence, the exercise of which can be a transformative experience. This is one of the takeaways of research by UC Berkeley sociologist Elizabeth McKenna and Hahrie Han.25 McKenna and Han further stress the importance of giving campaign volunteers meaningful roles and opportunities to increase their responsibilities. By doing so, a campaign cultivates these individuals’ capacity for leadership, and ideally their future ability to effectively broker or make demands upon campaigns on behalf of their communities. This is part of how communities—especially those routinely cast as undependable voters, or otherwise left out—are grown as constituencies. Again, this end goal is distinct from that of winning an election. Existing research attests that it merits a model that diverges from the convention of spending heavily on mass-media advertising, mailers, and other less-personal and nonplace-based campaign tactics.26

Exclusionary Government as Demobilizing

Finally, a small but important set of recent studies have begun to investigate how the exclusionary policies and practices of government actors might impact civic participation and inclusion. Faculty cluster member Bertrall Ross has written on how the US Supreme Court’s recent jurisprudence withdraws support for congressional enhancements to the equal protection rights of minorities. Ross argues that this is part of a broad philosophical shift on the Court—a turn away from a pluralist view that, in a democracy, the law should defend advances toward greater inclusion.27

Zepeda-Millán and colleagues have studied another judicial dynamic with potentially demobilizing effects— the expansion of deportations. Specifically, they investigated how knowledge of mass deportation under the Obama administration affected young Latinos’ attitudes about the Democratic Party.28 These researchers found that once young US-born Latinos were informed that President Obama presided over more deportations than his predecessor, they were significantly less likely to rate the Democrats as “welcoming” to Latinos.29\ Street, Zepeda-Millán, and Jones-Correa note that most young Latinos are either “weak partisans” or independents, making such a change in attitude significant. At the same time, only 9 percent of their study’s respondents saw Republicans as “welcoming” to Latinos. Given this, it could be that policies that present the Democrats as “unwelcoming” still may not push US-born Latinos to the GOP. Rather, they might instead weaken their faith in government in general, among other things alienating them from the electorate altogether.

Cluster member Irene Bloemraad has also studied political engagement among young US-born Latinos in the context of mass deportation. In a recent publication, she and co-authors report that, among the Bay Area Latino teenagers they interviewed, those whose parents live in the US without authorization are no less likely to be politically active than those whose parents are citizens.30 Many of these daughters and sons of unauthorized residents participate in community organizing and political action for immigrant rights. Nonetheless, Bloemraad, Sarabia, and Fillingim explain that these young people feel a countervailing demand on their activism: to “stay out of trouble,” and avoid exposing themselves (or family) to unnecessary risks or attention. Together, this suggests that family members’ exposure to the threat of deportation inspires political mobilization, but it also carries restraints around the exercise of rights—a kind of “ripple” chilling effect.

There is a need for more focused research on the role of governing practices in mobilizing and demobilizing different subgroups of eligible voters. We know from post-2016 election surveys that the belief is widespread that “politics” or “the system” is rigged, and it spans primary-candidate and party preferences.31 Such signs of declining faith in democracy should concern us all. But at a time when policy stances from the White House paint the “we” of our representative government ever more narrowly, there is an even stronger imperative to ensure that those who are excluded may find reliable outlets and vehicles for political participation. For example, if certain identities are being picked out for marginalization, opposition political actors will only contribute to alienating and disillusioning those who are targeted if they run away from talk about said identities. Such segmented alienation has corrosive effects that extend beyond government into wider social relations; in short, it is bad for us all.

Civic Deliberation, Deception, and Public Trust

MORE THAN MIDWAY through 2018, we are still far from grasping all the ways in which the 2016 election was impacted by personal data breaches, the spread of intentionally false news stories, and other manipulation and distortion of information. While it is important to ask how much these phenomena hurt which candidate(s), more important are questions about how they compromise the longer-term health of our democracy. Election cycles are meant to provide voters with opportunities for meaningful debate and choice, grounded in a relatively shared understanding of the basic facts and stakes involved. This shared base of understanding is crucial if voters are to make choices informed by dialogue with fellow citizens—not as isolates, but with a sense of the public interest. As faculty cluster member Sarah Song reminds us, deliberation is a crucial democratic activity that depends on good-faith commitments to listening to, understanding, and seeking common ground with one another in a diverse society.32

Inclusive, constructive civic debate is not stymied by voters having very different ideas about what they want33 —about what ought to be. But it will not thrive where there are dramatically different notions of what is and who “we” are. Recent research by faculty cluster affiliates explains some of the major trends and beliefs currently straining our capacity for inclusive democratic deliberation.

Dog-Whistle Politics: Deceit and Division

Haas Institute senior fellow and Berkeley Law professor Ian Haney López has extensively analyzed one particularly long-standing tactic of deception and division: dog-whistle politics. A form of political discourse, dog-whistle politics involves the use of coded messages to appeal to constituents’ racial anxieties and stereotypes, but while avoiding overtly racial language that might put off many voters. Indeed, the racial content of such messages is meant to be perceptible only to responsive audiences, hence the term “dog whistle.” Dog whistling plays on these audiences’ latent racist beliefs and prevalent racial narratives, stimulating fears that can, at the same time, be plausibly explained away in alternative, non-racial terms.34

Haney López is clear that dog whistling has historically been deployed purely for calculated political gain—to net as many votes as possible. It may or may not in reality reflect an earnest racism or white-favoring policy agenda on the part of the politicians who use the tactic. In fact, Haney López emphasizes that dogwhistle politics has tended to be about racializing social programs to stoke anti-tax and anti-government sentiments that will ultimately benefit corporate interests and the politicians who champion them.35 By enabling a candidate to convey different commitments to different constituencies, dog-whistle politics is a form of deception. Its logic is an attack on inclusive civic deliberation because it intentionally diminishes voters’ capacity for informed discourse and choice.

Even more harmful however is that dog-whistle politics activates, stirs, and stokes racial animus. Irrespective of its narrower strategic goals, politicians’ dog-whistle messages strengthen and embolden the racist beliefs and narratives they covertly affirm. Haney López argues that countering these divisive scripts requires exposing them for what they are, as well as spreading alternative narratives that “fashion an inclusive sense of linked fate.”36

The current political moment would seem to present us with new questions about the relationship between “dog-whistling” and increasingly prevalent racial “bullhorns.” Do the latter compromise the former by exposing their underlying meanings? Or do they make dog whistles even less perceptible by contrast? What does the rise of bullhorns mean for Haney López’s point that dog-whistle politics is grounded in the need to obscure racist meanings? These are questions that will need to be answered if we are to know how to build bridges for a shared civic identity that both transcends and embraces the diversity of the country.

Distrust of Media and Civic Debate

Another major barrier to constructive public deliberation in the United States is the sharp disagreement over what are credible sources of information. A forthcoming research brief by Taeku Lee, Jessica Mahone, and Joe Goldman shows that distrust in “mainstream media” is common and widespread. The December 2016 wave of these researchers’ Voter Study Group survey panel found 72 percent of respondents saying they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that “You can’t believe much of what you hear from mainstream media.”37 As the authors note, this is consistent with a growing body of evidence that trust in media is in decline, and attitudes about the legitimacy of national news ever more polarized.

US voters thus increasingly operate politically without shared authorities on “the facts,” and presumably divergent bases for understanding key social and political issues. Distrust of media is particularly damaging to prospects for fruitful public debate given the prevalence of misinformation and disinformation on online platforms, and their ability to spread rapidly on social media. It means that mainstream outlets cannot effectively serve a fact-checking role; existing research suggests that alternative, “crowdsourced” fact-checking has been unable to fill the void.38

Lee, Mahone, and Goldman further find that among those who express distrust of mainstream media, support for democracy as a political system is markedly lower. This is likely due in part to the fact that distrust in media correlates strongly with other forms of skepticism. These include reluctance about trusting “most people,” the government, and “experts and intellectuals,” as well as the belief that the political system is “rigged.”39 Given this type of wide-ranging distrust, why would someone consider democracy necessarily and “always preferable to other political systems?”

Distrust, Exclusionary Views, and Alienation

The brief by Lee and his co-authors also shows that distrust in mainstream media has a major influence on support for exclusionary policies. Of all the variables tested in their regression models—including income, ideology, and MSNBC and Fox News viewership— Lee, Mahone, and Goldman show that media distrust has the strongest predictive relationship to support for a Muslim travel ban and opposition to a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Distrust of mainstream media is also among the strongest predictors of opposition to affirmative action and the belief that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against African Americans.40 The ties between media distrust and more generalized cynicism pose a formidable challenge for those committed to an inclusive electorate. They indicate, first, a retreat from the kind of civic solidarity needed to carry out constructive dialogue among people of different opinions. Without this basic foundation, spaces of participation and belonging will be distributed unevenly—and very likely stingily. The picture becomes even bleaker in light of the correlations between distrust and myriad groupbased exclusionary views. Here any effort to bridge across social difference, or even to reduce the force of othering inevitably runs up against the additional hurdle of an audience disposed to fundamentally distrust those with whom they do not already agree.

Here again, it is not clear that social media is serving as a conduit for more inclusive dialogue and civic participation. On one hand, there is evidence that popular talk of “echo chambers” and “information cocoons” is exaggerated, and that social media do in fact increase most people’s exposure to a diversity of views.41 On the other, a significant volume of information shared on Facebook and Twitter comes from hyperpartisan platforms that—together with intentionally false news—are often designed to provoke outrage, animus, and division. These affective responses in turn lead to more online “shares,” spreading exposure to hyperpartisan, uncivil debate.42 Such exposure is not only polarizing; it can also further alienate those who are already excluded and pessimistic about whether political participation has the potential to improve their lives.

The road map for addressing these problems, in the short or the long term, is not as well researched as some of the other issues discussed here. This is in part due to the relative novelty of the technologies that drive, subdivide, and channel information to different audiences—including information telling us that we should not trust one another. Policymakers in many cases lack sufficient knowledge about how these technologies work, and there is also still too little research on the nature of users’ relationships with the technologies. What is clear is that we are living a period of significant fragmentation and cynicism about public life. There is an urgent need for compelling and culturally salient counternarratives that support inclusive conceptions of civic debate and solidarity, and inoculate against the worst forms of division.

Concluding Recommendations

THE PRECEDING SECTIONS have synthesized recent research identifying some historical barriers and ongoing threats to achieving an electorate that truly represents the country. This research brings forward evidence of structures and processes that stoke division and deter political participation, making clear that chronic turnout gaps are about much more than individual choices. On one hand, this makes problems of disengagement and disaffection appear much more daunting and entrenched. On the other, it spotlights them as issues of social—and in many cases, racial— justice. Such issues always involve deep historical and structural components, but this has never been a reason to run from them.

From the research profiled in this brief, a number of recommendations emerge. These recommendations speak not only to public officials and policymakers, but also to researchers, analysts, advocates, donors, and philanthropists—especially those committed to raising voter participation levels among the most under-represented voter groups.

For researchers, pollsters, journalists, and other public knowledge-makers

+Carry out regular and concerted efforts to collect and disseminate information on the views and dispositions of inconsistent or “drop-off” voters, as well as non-voters.

+Make changes to public opinion polling methodology to (1) catch up with the degree of demographic changes that have taken place in the country, and (2) correct for race, gender, and consistent-voter biases.

+Design research and dissemination strategies to lift up examples of civic-engagement programs and practices that have been successful in activating the most hard-to-reach voter groups.

+Exercise critical discretion in the adoption and reproduction of social identity categories. Review in particular any use of identity terms where said terms were not a part of data collection, such as labeling those who reported not having attained a Bachelor’s degree as “working class.”

+Design and carry out studies to understand what impact the changes to the 2020 Census’s race question have on identity and self-identification patterns.

+Practice greater discretion, and provide necessary caveats and contextualization, when using demographic forecasts and projections in relation to the future electorate.

+Design and carry out research on the social and political effects of racial and xenophobic “bullhorn” messages, and on how these messages function in relation to decades-old dog-whistle tactics.

For donors and philanthropists

+Invest in organizational capacity and infrastructure of groups doing relational, yearround organizing and civic engagement with communities of color and young people.

+Redirect giving from one-off Get-Out-the-Vote canvasses to longer-term projects that make multiple contacts with target voters.

+Invest in projects that train and cultivate local leaders who will remain in their communities as skilled resources, organizers, and possible future elected representatives.

+Partner with projects that are developing and testing narrative frames that bridge across existing social identities and formulate an inclusive civic identity.

+Support arts and cultural strategists working to engage hard-to-reach populations in civic life.

+Examine the ways funded projects, including research, might be strengthening identity categories that are imposed or contested, or that foment social exclusion or exclusionary forms of self-identification.

For policymakers and public officials

+Evaluate, as through commissioned studies, how existing public policies impact voter participation. This evaluation should not be limited to electoral policies alone, but also the wider panoply of policies related to social inclusion or exclusion, civic engagement or alienation.

+Do not ignore, but instead effectively counter, divisive racial or other exclusionary narratives emanating from public figures. Failure to speak to questions of identity— both the differentiating and the unifying “we” components in our society—is alienating to those who have long been excluded, and bad for social trust and confidence in public officials in general.

+Commit to expose and denounce coded racist messaging, even when it comes from fellow members of one’s own party or agency.

+Abstain from adding or altering official ethnoracial identity categories where the changes have not been broadly advocated by civic groups, studied by impartial researchers, and field tested across multiple sites.

+Abstain from, and commit to countering, efforts to delegitimize nonpartisan news media. Criticism of media outlets’ coverage of events is constructive; discrediting and vilifying news media in general is harmful.

- 1Joshua Clark, “What Didn’t Happen? Breaking Down the Results of the 2016 Presidential Election,” Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, November 2017.

- 2john a. powell and Stephen Menendian, “The Problem of Othering: Towards Inclusiveness and Belonging,” Othering & Belonging 1(1): 14-39 (2016).

- 3Taeku Lee, Mobilizing Public Opinion: Black Insurgency and Racial Attitudes in the Civil Rights Era, The University of Chicago Press, 2002. See Chapter 3.

- 4Ibid., p. 90

- 5Sina Odugbemi and Taeku Lee, “Taking Direct Accountability Seriously,” in Sina Odugbemi and Taeku Lee, eds., Accountability through Public Opinion: From Inertia to Public Action, The World Bank, 2011.

- 6Kevin M. Esterling, Archon Fung, and Taeku Lee, “How Much Disagreement is Good for Democratic Deliberation?” Political Communication 32(4): 529-551 (2015); and Kevin M. Esterling, Archon Fung, and Taeku Lee, “Modeling Persuasion within Small Groups, with an Application to a Deliberative Field Experiment on U.S. Fiscal Policy,” working paper on file with the author.

- 7Clark, “What Didn’t Happen?”

- 8G. Cristina Mora, Making Hispanics: How Activists, Bureaucrats and Media Constructed a New American, The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- 9Even so, we should not downplay the potency of certain institutional events—such as the US Census Bureau’s choice to collect data on people as “Hispanic origin”—in cementing a category’s social significance.

- 10Furthermore, many analyses conflate these, cover up their own conflations, and thereby contribute to reifying and naturalizing the “WWC” they purport only to investigate. Clark, “What Didn’t Happen?”

- 11Michael Jones-Correa, Sophia J. Wallace, and Chris Zepeda-Millán, “The Impact of Large-Scale Collective Action on Latino Perceptions of Commonality and Competition with African Americans,” Social Science Quarterly 97(2): 458-475 (2016).

- 12Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, Insights from the 2016 VOTER Survey, at www.voterstudygroup.org/publications/2016- elections.

- 13By way of contrast, the proposal to add a separate “Middle Eastern or North African” category to the 2020 Census form had been pushed by a broad network of advocacy groups and thoroughly researched over many years. Nonetheless, it was recently scuttled.

- 14Consider, for example, the man who founded an organization to stage heavily armed protests against the “Islamicization of America” outside mosques in Texas. Profiled in The Washington Post, he applauded the media and public attention to “working-class whites,” which he felt made him part of something both powerful, and importantly, not “fringe.” “It’s not like I’m Joe Blow anymore,” he said. “I have a name, and people would listen.” That name—the one that made him feel like “more than a man with a Facebook account, a passion and a gun,” as the Post reporter put it—is “white working class.” Robert Samuels, “A showdown over Sharia,” The Washington Post, September 22, 2017.

- 15G. Cristina Mora and Michael Rodríguez-Muñiz, “Latinos, Race, and the American Future: A Response to Richard Alba’s ‘The Likely Persistence of a White Majority’,” New Labor Forum 26(2): 40-46 (2017).

- 16Faculty cluster member Michael Omi has written a number of widely cited critical analyses of the socio-historical contingency of ethno-racial categories in US official statistics. See for example, Michael Omi, “Racial Identity and the State: The Dilemmas of Classification,” Law and Inequality 15(1): 7-23 (1997).

- 17In contrast, Taeku Lee proposes that social scientists consider an alternative system of ethno-racial self-identification wherein survey respondents may allocate “points” across a range of identity categories. This would make projects to measure identity better reflect identity’s conceptualization in social theory as multiple and fluid. Taeku Lee, “Between Social Theory and Social Science Practice: Toward a New Approach to the Survey Measurement of ‘Race’,” in Rawi Abdelal, Yoshiko M. Herrera, Alastair Iain Johnston, and Rose McDermott, eds., Measuring Identity: A Guide for Social Scientists, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- 18Clark, “What Didn’t Happen?,” pp. 9-12.

- 19Joshua Clark, “Widening the Lens on Voter Suppression: From Calculating Lost Votes to Fighting for Effective Voting Rights,” Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, July 2018.

- 20Lisa García Bedolla and Melissa R. Michelson, Mobilizing Inclusion: Transforming the Electorate through Get-Out-the-Vote Campaigns, Yale University Press, 2012.

- 21Ibid.

- 22Among the notable structural conditions are racial and partisan gerrymandering, and the position of money in politics, both of which distort campaigns’ and politicians’ incentives to court, represent, and be held accountable by certain segments of their constituencies. Restrictive voting laws that blatantly target groups like African Americans, Latinos, or young people also foster or strengthen cynicism about political participation among those affected. See further, Clark, “Widening the Lens on Voter Suppression.

- 23García Bedolla and Michelson, Mobilizing Inclusion

- 24For an example, see García Bedolla and Michelson’s discussion of a successful door-to-door experiment in which new and non-citizen Latinos canvassed among Latino “infrequent voters.” Ibid., pp. 118- 119.

- 25Elizabeth McKenna and Hahrie Han, Groundbreakers: How Obama’s 2.2 Million Volunteers Transformed Campaigning in America, Oxford University Press (2015).

- 26Ibid.

- 27Bertrall L. Ross, “Democracy and Renewed Distrust: Equal Protection and the Evolving Judicial Conception of Politics,” California Law Review 101(6): 1565-1640 (2013)

- 28Alex Street, Chris Zepeda-Millán, and Michael Jones-Correa, “Mass Deportations and the Future of Latino Partisanship,” Social Science Quarterly 96(2): 540-552.

- 29\Ibid.

- 30Irene Bloemraad, Heidy Sarabia, and Angela E. Fillingim, “‘Staying out of Trouble’ and Doing What Is ‘Right’: Citizenship Acts, Citizenship Ideals, and the Effects of Legal Status on SecondGeneration Youth,” American Behavioral Scientist 60(13): 1534- 1552 (2016).

- 31Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, Insights from the 2016 VOTER Survey

- 32Sarah Song, “What does it mean to be an American?” Dædalus 138(2): 31-40 (2009).

- 33Esterling, Fung, and Lee, “How Much Disagreement is Good for Democratic Deliberation?”

- 34Ian Haney López, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class, Oxford University Press, 2014

- 35Ibid.; and Ian Haney López, “California Dog Whistling,” Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley, April 2018.

- 36Haney López, “California Dog Whistling.”

- 37Taeku Lee, Jessica Mahone, and Joe Goldman, “Public Trust of Mainstream Media,” Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, forthcoming in 2018.

- 38Data scientists at Facebook find that users’ efforts to fact check false or dubious information shared on their platform tend not to be able to keep up with the information’s ease and speed of proliferation. Adrien Friggeri, Lada A. Adamic, Dean Eckles, and Justin Cheng, “Rumor Cascades,” Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 101-110 (2014).

- 39Lee, Mahone, and Goldman, “Public Trust of Mainstream Media.”

- 40Ibid.

- 41Andrew Guess, Brendan Nyhan, Benjamin Lyons, and Jason Reifler, “Avoiding the Echo Chamber about Echo Chambers: Why Selective Exposure to Like-Minded Political News is Less Prevalent than You Think,” Knight Foundation, 2018.

- 42A. Hasell and Brian E. Weeks, “Partisan Provocation: The Role of Partisan News Use and Emotional Responses in Political Information Sharing in Social Media,” Human Communication Research 42(4): 641-661 (2016).