Collectively, across international humanitarian law, human rights law, refugee law, and other bodies of law, protections for climate-induced displaced persons forced to cross international borders are limited, piecemeal, and not legally binding. This report argues that a comprehensive framework for climate-induced displaced persons forced to cross international borders— “climate refugees”—is necessary and that it needs to be applicable to two specific situations:

- persons moving across internationally recognized state borders as a consequence of sudden-onset or slow-onset disasters; and

- persons permanently leaving states no longer habitable (including “sinking island states”) as a consequence of sudden-onset or slow-onset disasters.267

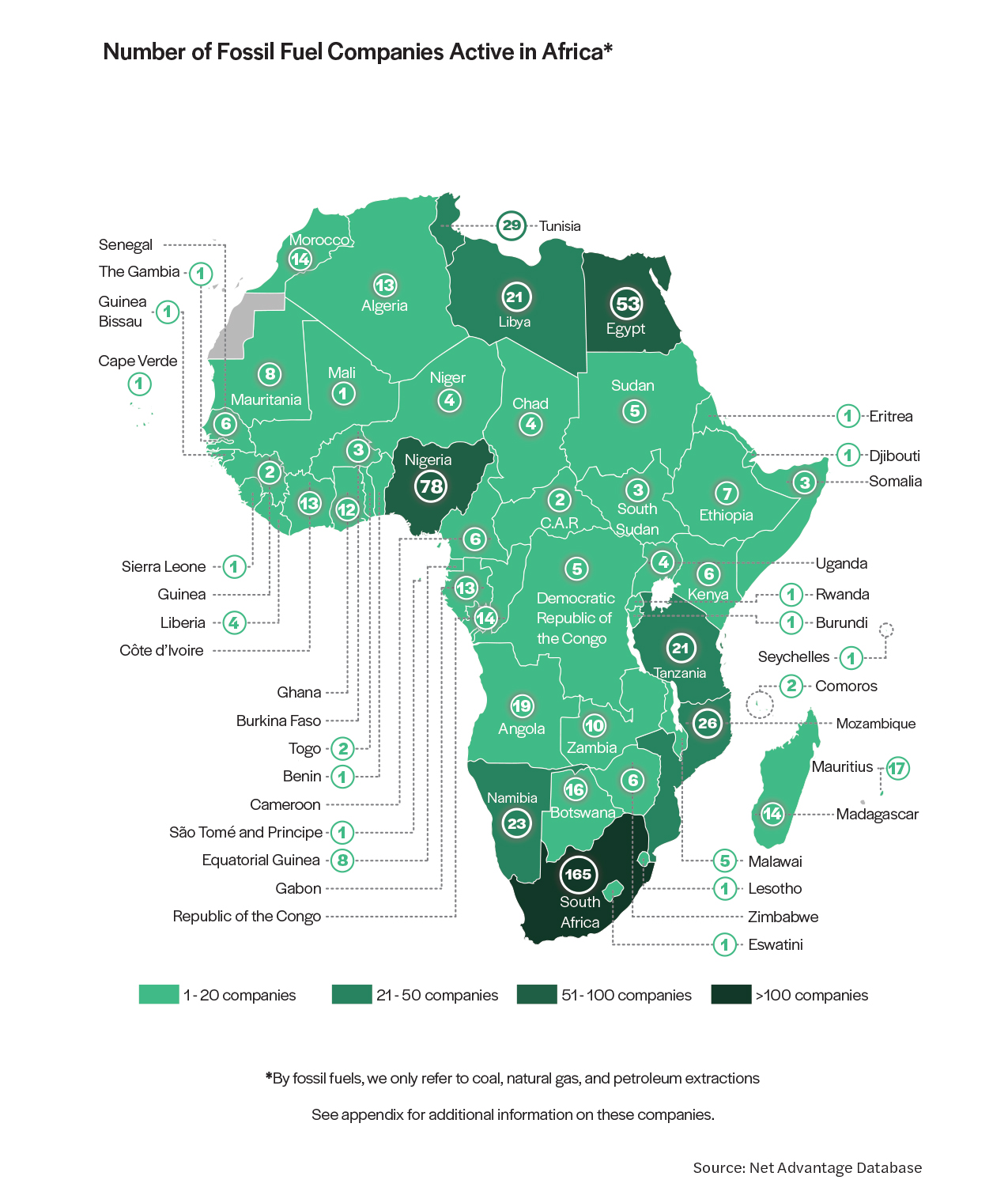

This report targets a key condition for refugee status: “persecution.” Specifically, this report advances a new deterritorialized understanding of “persecution” under the climate crisis, which accounts for the ability of one to survive and avail themselves of a sufficient degree of protection within their country of origin. It does so while recognizing that the “actors” of persecution and the respective climate crisis impacts are fundamentally indeterminable. Although the climate is changing due to a number of sources, this report focuses on the “persecution” that is built into our global dependence upon petroleum, coal, natural gas, and other fossil fuels, and the global investment patterns behind this dependence. In short, the focus is on “petro-persecution,” which operates across the world economic system and regional, national, and local levels.

The Climate Crisis and the World Economy

COAL, OIL, NATURAL GAS, and other fossil fuels are the primary source of energy today and have long fueled global economic development. Yet the burning of fossil fuels for energy and the dependence of entire industries and industrial processes upon such fossil fuels (e.g., industrial agriculture, steel production, and other manufacturing) has produced catastrophic changes in the earth’s climate, putting the world’s most vulnerable communities at risk.

This section recounts the importance of fossil fuels to the strengthening of corporations and capitalist nations in particular, attending to the subservience of the latter to the former. It includes the global significance of such developments and addresses how, following such histories and the consolidation of the resolutely capital world economy, every nation—regardless of their political system and ideology—is subject to the global economic dependence on fossil fuels. It looks at two ways this global dependence on fossil fuels has been sustained, imbricating capitalist and noncapitalist nations alike: firstly, US efforts to maintain the US dollar as the reserve currency for key international commodities, especially oil, and secondly, the investment priorities of the world’s largest banks.

Fossil Fuels and the Rise of State and Corporate Power

The concentration of energy within centralized stocks of fossil fuels, such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas, was a boon to the growing capitalist economies of Europe, the United States, and elsewhere, ultimately transforming cities and towns from energy-scarce sites into locations of energy superabundance as the limits to growth were contained. Although capitalist economic growth did not begin with fossil fuels, fossil fuels were critical to the labor control and exploitation that capitalism demanded as part of such growth.

Specifically, capitalism first ran on renewable energy—namely, solar and hydropower—and even when the transition to coal took off in the 1830s, a vast majority of hydropower remained relatively untapped and inexpensive. When rivers ran low and factories closed, bosses expected workers to return whenever there was sufficient water, demanding excessively long working hours. As a result, the first and foremost demand of the emerging labor movement was the fight for the “working day.” The 1833 Factory Act, for example, was an attempt to establish a regular working day in textile manufacturing.

Coal solved such early labor issues for capitalists by allowing production to take place anywhere and anytime. Aiding their counterattacks against such workers demanding fairer working conditions, factories with coal-powered steam engines could be placed in towns, where unemployment and state crackdowns on labor movements weakened workers’ resistance to the demands of capitalism. Together, across the capitalist economies of Europe and its extensions elsewhere, coal was not only essential to empowering state and corporate actors but also securing the state’s largely subservient role to capital.268

The mid-twentieth century’s development of cheap and abundant energy from oil only intensified the paired rise of state and corporate power across Europe, the United States, and elsewhere. This was especially clear in the United States. The first massive corporations in the United States were railroad companies, which used coal and the steam engine as they aided the development of the United States from the industrial revolution in the Northeast (1810–1850) to the settlement in the West (1850–1890). Yet, as political theorist Timothy Mitchell argues, the material composition of oil, the requirements of exploration, and the production process were a boon to the US government and oil companies alike, for these features of oil allowed for the concentration of expertise in the hands of select engineers, scientists, and capitalists.269 Case in point: the rise of Standard Oil and its command of capital and state power.

Established in 1870 by John D. Rockefeller and Henry Flagler, Standard Oil dominated the oil products market initially through horizontal integration in the refining sector, then in later years, vertical integration—acquiring pipelines, railroad tank cars, terminal facilities, and barrel manufacturing factories. The company was also an innovator in developing the business trust, where the stockholders of Standard’s group of companies transferred their shares to a single set of trustees who controlled all of the companies. The Standard Oil trust streamlined production and logistics, lowered costs, and used aggressive pricing to destroy competitors in production, distribution, and retail. In 1904, Standard Oil controlled 91 percent of oil production and 85 percent of final sales in the United States.270

In 1911, the US Supreme Court ruled, in a landmark case, that Standard Oil was an illegal monopoly, necessitating the dissolution of its trust into 34 smaller companies. Yet, the processes that defined Standard Oil’s ascendance are still commonplace. Integration downstream, including acquiring retail networks of gas stations, and integrating upstream, such as the buying of oil- and gas-producing fields and exploration leases, are defining features of corporate power in the United States and other capitalist nations. These dynamics ramped up again in the 1970s and 1980s. With mega-mergers in the 1990s and 2000s creating major corporations like ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil, Standard Oil’s successors are still among the companies that generate the largest profits worldwide.271

As before, their growth did not happen without state support. Despite the dissolution of Standard Oil, in the past 100 years, the federal government has put more than $470 billion into the oil and gas industry in the form of generous, never-expiring tax breaks. As early as the 1920s, oil and gas subsidies were averaging $1.9 billion a year in today’s dollars. Taxpayers currently subsidize the oil industry by as much as $4.8 billion a year, with about half of that going to five major oil companies—ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, BP, and ConocoPhillips—which get an average tax break of $3.34 on every barrel of domestic crude oil they produce.272

Fossil Fuel Dependency and the World Economy

Capitalism as a mode of organizing social and economic life began in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in northwestern Europe, especially in the Netherlands (Dutch Republic) and England. Yet from the beginning, it involved outward expansion, encompassing ever-larger areas of the world in a network of material exchanges and extraction. Over the following centuries, this network of exchange and extraction developed into a world market for goods and services, and an international division of labor. The process took place neither peacefully nor equitably, but instead through colonial and imperial expansion. By the end of the nineteenth century, the project of a single “capitalist world economy” had been completed. The grid of such exchange relationships now covered practically all peoples and parts of the world.

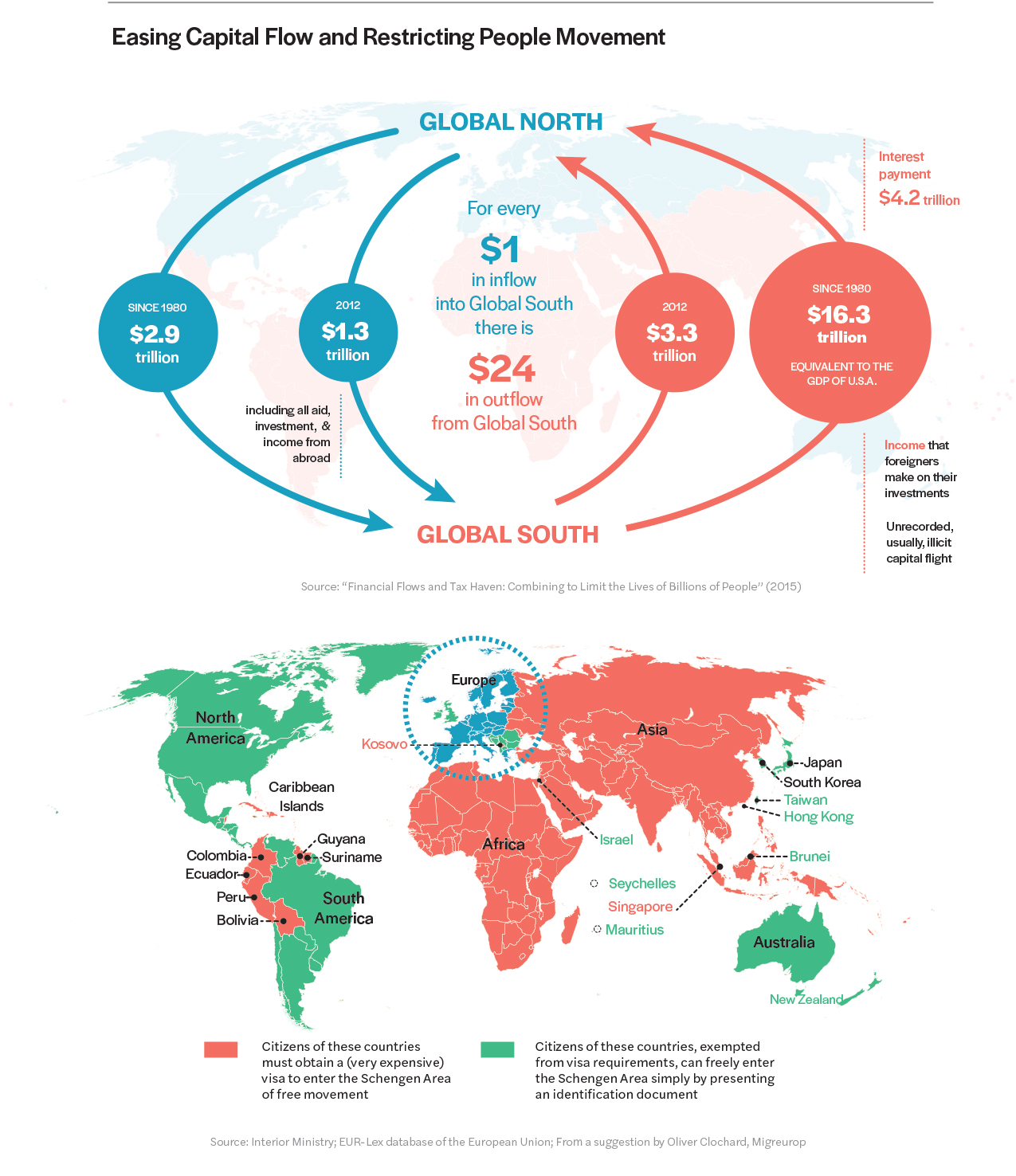

The development of this world economy involved a fundamental and lasting rift within and between parts of the world. More recently, this rift has been understood as one between the Global North and Global South. These terms—traditionally used within intergovernmental development organizations to refer to economically “advantaged” nation-states such as the United States and the European nations, and “disadvantaged” nation-states such as those across Latin America, Africa, and Asia—describes the colonial and postcolonial exploitation of the latter that has underpinned the global dominance of the former. Yet the Global South can also refer to the geography of capitalism’s externalities and subjugated peoples both within and beyond the borders of wealthier countries such as the United States and European nations.273

Fossil fuels were a boon to capitalist nations and corporate entities long after modern nations and capitalism had their start, as part of this world economy consolidated under the United States and European nations. Now every nation—capitalist or not—is forced to reckon with the global economic dependence on fossil fuels.274 Attempts by nations and international bodies to assert independence from this global regime have gone against US and European geopolitical interests and helped motivate economic and military responses. Such confrontations have taken place around the US dollar as the reserve currency for key international commodities, especially oil.

Saddam Hussein’s regime, for example, had increasingly traded Iraq’s oil in the euro, enhancing its value as an international currency competing with the US dollar. Likewise, Muammar Qaddafi had proposed the possibility of a common currency in the African Union.275 Although the 1990 US-led invasion of Iraq was premised on Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and the 2003 invasion was based on false claims that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction and links to Al-Qaida, and although the 2011 assault on Libya was based on that regime’s repression of civilians, the threats both leaders posed to the United States and its massive multinational fossil fuel corporations were motivating factors for the conflicts intended to depose them.

In 2019, the US Treasury Secretary, Steven Mnuchin, warned European nations to abide by US sanctions on Iran—targeting Iran’s oil exports following the 2018 US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—or they will be banned from using the dollar system for international transactions. Thus, against such threats to US and European states and corporate power and the fossil fuel-dependent capitalist world economy more broadly, the world has seen intensification of war by financial and other nonmilitary means.

Our capitalist world economy and dependence on fossil fuels have also been sustained, in part, by the business practices of the major banks of Europe and North America. A 2019 report released by Rainforest Action Network, BankTrack, Indigenous Environmental Network, Oil Change International, Sierra Club, and Honor the Earth reveals that 33 global banks have provided $1.9 trillion to fossil fuel companies since the adoption of the Paris Agreement at the end of 2015. The amount of financing has risen in each of the past two years. Of this $1.9 trillion total, $600 billion went to 100 companies that are most aggressively expanding fossil fuels extraction, refining, and distribution.

The four biggest global bankers of fossil fuels are all US banks—JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citibank, and Bank of America. Barclays of England, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group of Japan, and RBC Royal Bank of Canada are also massive funders in this sector. Notably, JPMorgan Chase is by far the largest banker of fossil fuels extraction and expansion—and therefore the world’s worst banker financing the climate crisis. Since the Paris Agreement, JPMorgan Chase has provided $196 billion in finance for fossil fuels, nearly 10 percent of all fossil fuel finance from the 33 major global banks.276

US Disengagement in Climate Crisis Mitigation and Adaptation

The predominantly US-led bankrolling and state-led militarized protection of fossil fuel interests has gone hand in hand with the United States’ disengagement from international efforts to challenge the global dependence upon fossil fuels. In 2015, after two decades of talks, 195 countries agreed to curb greenhouse gas emissions, adapt to the adverse impacts of the climate crisis, and foster and finance climate-resilient development starting in the year 2020. The Paris Agreement sets out to enhance the implementation of the UNFCCC and push countries to set targets beyond previously set mitigation, adaptation, and finance targets.

Yet in June 2017, President Donald Trump announced that the United States—the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases after China, with the European Union a distant third—would withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Justifying his decision, President Trump stated that the agreement is “less about the climate and more about other countries gaining a financial advantage over the United States”—highlighting the concern that a meaningful curb on emissions would affect the profits, power, and reach of US multinational corporations.277

The United States’ resistance to the Paris Agreement has not been limited to the current administration. During the September 2016 ratification, then-US secretary of state John Kerry stated that “[e]ach day the planet is on this course, it becomes more dangerous.…[I]f anyone doubted the science, all they have to do is watch, sense, feel what is happening in the world today. High temperatures are already having consequences, people are dying in the heat, people lack water, we already have climate refugees.”

After US negotiators demanded the exclusion of language that could allow the agreement to be used to claim legal liability for the climate crisis, critics said the agreement would still condemn hundreds of millions of people living in low-lying coastal areas and small islands to a precarious future. These announcements undermine ongoing efforts toward climate mitigation, adaptation, and finance, within and outside the agreement. Further, they undermine more expansive accounts of the climate crisis itself that had begun to surface in recent years, including acknowledging its effects with regard to mass migration.

Because of the federal-level disengagement with climate mitigation and adaptation, and decarbonization—including the Paris Agreement, one of the strongest displays of global willingness to take urgent action—various communities and public and private actors have instead made some ground. As Christiana Figueres, the former UN climate chief who delivered the Paris Agreement, remarked, “[s]tates, cities, corporations, [and] investors have been moving [toward climate mitigation and adaptation] for several years and the dropping prices of renewables versus high cost of health impacts from fossil fuels, guarantees the continuation of the transition.”

Such has been the case within the United States itself, where states have already pushed back on Trump’s decision and vowed to adhere to the principles of the Paris Agreement. For example, only one week after President Trump’s announcement, Hawaii became the first state to enact legislation aligning with the Paris Agreement. The bills signed by Hawaii Governor David Ige were SB 559 (Act 032) and HB 1578 (Act 033). HB 1578 establishes a Carbon Farming Task Force, and SB 559 expanded “strategies and mechanisms” to cut greenhouse gas emissions across the state “in alignment with the principles and goals adopted” in the Paris Agreement.

“Petro-Persecution,” Migration, and the Fossil Fuel-Dependent World Economy

EVEN ABSENT THE CLIMATE CRISIS, “persecution” from sources outside one’s country of origin is a fundamental feature of our capitalist world economic system. As stated, the nation-states of the Global North include the United States and European nations, and the nation-states of the Global South include those across Latin America, Africa, and Asia, with the colonial and postcolonial exploitation of the latter underpinning the global dominance of the former. Ultimately, the structural vulnerability and mass expulsions that have followed from exploitation of the Global South by the Global North have been met with militarized borders, criminalization of migration, fewer resettlements, and limited refugee protections.278 The ultimate goal: to secure wealth from the Global South and inhibit its redistribution back to the Global South via subsequent migration of workers and remittances, among other means.279

Under the climate crisis, these features of the world economic system and its dependence on fossil fuels become much clearer. It is evident in the exploitation of the most marginalized communities in the extraction, refining, and distribution of fossil fuels and in the impacts of the crisis on impoverished communities that derive the majority of their incomes from agriculture, fishing, and wildlife. State- and corporate-backed dependence on fossil fuels belabors the deterritorialized “persecution” that many communities will continue to face from sources within and outside their own country of origin, especially when climate refugees from the Global South seek resettlement in the Global North. In 2018, for example, the Internal Australian Defence Force predicted the military may be forced to increase patrols in Australia’s northern waters to deal with “sea-borne migration” sparked by rising sea levels in the Indo-Pacific region.

This section argues that two dynamics—neoliberalization and securitization—describe deterritorialized “persecution” inherent to the present-day capitalist world economy and “petro-persecution” under the climate crisis in particular. It explores governing the relatively unhindered flow of wealth and resources from the Global South in conjunction with efforts to stem subsequent migration and resettlement.

“Petro-Persecution” and Neoliberalization

The first dynamic of transnational “persecution” specific to the present-day system of a capitalist world economy is neoliberalization. The term describes the late-twentieth century reinterpretation and exercise of state and political power modeled on market-based economy values and the expulsions, displacements, and exclusions that follow therefrom.280 Within migration research, the dynamic of neoliberalization and its effects on migration have been effectively accounted for when placed within a Global North-Global South frame, offering some coherence to patterns of displacement and the reluctant, provisional, and seemingly arbitrary nature of resettlement today.

While it is a global phenomenon, neoliberalization since the 1970s has affected the Global North and the Global South in different ways, shaping contemporary removals, exclusions, and mobilities within and across each. As David Lloyd and Patrick Wolfe argue, in the Global North, neoliberalism has manifested in cuts to, and the privatization of, state-furnished public services, from public utilities, education, and health care, to social welfare, public space, and other services (i.e., “austerity”). The rationale is clear: to the neoliberal state, these public goods represent vast storehouses of capital, resources, services, and infrastructure and, thus, targets for expropriation and exploitation.281

These enclosures have been devastating for the general public in countries within the Global North, with unemployment, out-migration, foreclosures, poverty, imprisonment, and higher suicide rates having become central features of this transformation. These outcomes can be understood as their own displacements of sorts, such as displacement from one’s home and neighborhood vis-à-vis the foreclosure and real estate crises of the 2000s, and from society more broadly vis-à-vis the exponential growth of the prison population in recent decades.282

Like the Global North’s experience of austerity, the Global South has experienced its own version of neoliberalization. The imposition of debt repayment priorities and the opening of markets to powerful foreign firms weakened states throughout the Global South. Such measures ultimately impoverished the middle class and undermined local manufacturing, which could not compete with large mass-market foreign firms.283 These acquisitions were made possible by the explicit goals and unintended outcomes of International Monetary Fund and World Bank restructuring programs implemented in much of the Global South in the 1970s, as well as the demands of the World Trade Organization from its inception in the 1990s and onward. Saskia Sassen, sociologist of globalization and migration, argues the resulting mix of constraints and demands “had the effect of disciplining governments not yet fully integrated into the regime of free trade and open borders, and led to sharp shrinkage in government funds for education, health, and infrastructure.”284

Like austerity in the Global North, these dynamics across the Global South have precipitated their own removals, exclusions, and limits on mobility. Specifically, neoliberalization across the Global South has produced and exacerbated local, national, and regional resource and power conflicts. Oftentimes taking the form of war, disease, and famine, these conflicts are significant proximate causes of displacement.285

The links between the climate crisis, climate-induced migration, and neoliberalization are apparent in the effects that deregulation and privatization of state sectors and industries have had on the Global South in the late 1970s. These measures have contributed to the long-standing underdevelopment of national economies and industries, thus helping decrease resilience to the climate crisis. Specifically, they have not only helped increase poverty and undermine the development of adequate infrastructure that might help communities cope. They have also reentrenched NorthSouth relations of dependency that have forced many such countries into deriving a relatively large percentage of their GDP from agriculture, forestry, and fishing, which are by nature more vulnerable to a changing climate.286

As of 2015, an estimated 79 percent of those experiencing poverty live in rural areas, with most rural people relying on activities within food systems—most prominently primary production—for their livelihoods.287 As such, a large majority of the world’s poor depend on moderate seasonal changes to produce their food. Yet with strengthened natural disasters and unpredictable weather patterns— hotter days, drier seasons, more flooding, and shorter growing seasons—such communities are losing one of their few assets, knowing when to sow and harvest.288

Neoliberalization has exacerbated the pressure of the climate crisis on already-fragile low-income rural economies.289 Current trends of climate-induced displacement and the challenges of resettlement can only be expected to worsen. For example, Somalis have temporarily resettled in Kenya and Ethiopia; citizens of island states, such as Tuvalu, Nauru, and Kiribati, have tried to relocate to Australia and New Zealand; and Bangladeshis have resettled in India and Nepal.290 All of these migrants are not granted legal status and are either eventually deported or remain as undocumented immigrants.

Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that internal migration due to the climate crisis may ultimately create more economic and political refugees. The former UN high commissioner for refugees, Antonio Gutierrez, stated that “climate refugees can exacerbate the competition for resources—water, food, grazing lands—and that competition can trigger conflict.”291 Hence, climate crisis migration can cause population pressures, landlessness, rapid urbanization, and unemployment, which put refugees in danger of backlash and worsen existing urban struggles.

“Petro-Persecution” and Securitization

The second dynamic of transnational “persecution” specific to the present-day system of a capitalist world economy is securitization, which is intimately linked with the first dynamic of neoliberalization. During the past several decades, the role of the state has been redrawn to furnish a conduit for the more rapid distribution of what were once “public goods” into the hands of corporations and other private interests.292 Such demands that capital has placed upon states within both the Global North and the Global South have led to security concerns and the need for the state-led management of such concerns.293 Specifically, neoliberalization has brought with it not only austerity in the Global North and debt in the Global South, but also the paired dynamic of “securitization”—new strategies and efforts by states to manage the expulsions, and resource and power conflicts that have followed therefrom.

Like neoliberalization, the dynamic of securitization has developed across the Global North and the Global South in different ways, shaping contemporary removals, exclusions, and limits on mobility within and across each. And like neoliberalization, the dynamic of securitization offers some coherence to the reluctant, provisional, and seemingly arbitrary nature of resettlement today.

Across each hemisphere there has been no shortage of examples of the pairing of neoliberalism’s austerity and debt regimes, and new security concerns and claims on mobility to deal with the expulsions born of such regimes: Greece’s financial crisis and the disputes over polices pushed for from the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, alongside what Human Rights Watch has described as the growing crisis of xenophobic violence toward immigrants and political refugees across the country; the British austerity narrative promoted by the Conservatives, alongside policies and bills preventing terrorism, such as the government’s Draft Investigatory Power Bill; and the growing use of force by state actors, such as deploying housing eviction officers, and growing control of citizen participation initiatives, such as neighborhood renewal partnerships in the United Kingdom and the United States, or citizen security programs across Latin America where police are key partners.294

The links between the climate crisis, climate-induced migration, and securitization are apparent in that military institutions have been playing an increasingly prominent part in the governing of environmental concerns and that the climate crisis is being used by the military, researchers, politicians, and others to prop up the national security state. For example, on July 27, 2008, the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), alongside the US military, scientific institutes, public policy institutes, private corporations, national funding agencies, and news agencies, carried out a two-day, new type of military exercise called the “Climate Change War Game.” The exercise was intended “to explore the national security consequences of climate change.” The CNAS was perhaps the first in a growing number of “homeland security” institutions involved in environmental changes and the conflicts and displacements that have followed.295

More recently, a January 2019 US Department of Defense report, entitled “Report on Effects of a Changing Climate to the Department of Defense,” found that the climate crisis threatens a majority of mission-critical military bases. In its assessment of those 79 installations—which included Army, Air Force, and Navy installations—36 are threatened by wildfires, 43 are threatened by drought, and 53 are threatened by flooding. The report ultimately found that the effects of a changing climate pose a national security issue with potential impacts to Department of Defense missions, operational plans, and installations.296

Concerns of destabilized national borders, cascading violence, and mass migrations brought by the climate crisis, and the effects of the climate crisis on US military infrastructure, have been used to prop up US extraterritorial sovereignty. Such concerns are also driving the intranational contraction of US political subjects and spaces through increasingly militarized borders, fewer resettlements, criminalization of immigration, and limited refugee protections fueled by anxieties that more of those displaced peoples will reach the United States.297 For example, the Department of Defense’s “Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap 2014” states these concerns in detail:

“The impacts of climate change may cause instability in other countries by impairing access to food and water, damaging infrastructure, spreading disease, uprooting and displacing large numbers of people, compelling mass migration, interrupting commercial activity, or restricting electricity availability. These developments could undermine already-fragile governments that are unable to respond effectively or challenge stable governments, as well as increasing competition and tension between countries vying for limited resources. These gaps in governance can create an avenue for extremist ideologies and conditions that foster terrorism.”

The report continues, stating, “Here in the US, state and local governments responding to the effects of extreme weather may seek increased Defense Support to Civil Authorities”—the process by which US military assets and personnel can be used to assist in missions normally carried out by civil authorities. Thus, as the climate crisis affects the availability of food and water, human migration, and competition for natural resources, the report states that the “Department’s unique capability to provide logistical, material, and security assistance on a massive scale or in rapid fashion may be called upon with increasing frequency”—domestically and abroad.298

This drive for a resilient and prepared military presence in response to natural disasters and long-term environmental change goes hand in hand with an already-escalating presence on the border. For example, as of 2019, the Pentagon has been preparing to loosen rules that bar troops from interacting with migrants entering the United States, expanding the military’s involvement in migration from across the southern border. Specifically, senior defense officials have recommended that acting defense secretary Patrick Shanahan approve a new request from the Department of Homeland Security to provide military lawyers, cooks, and drivers to assist with handling a surge of migrants along the border.299

This drive for a resilient and prepared military presence in response to natural disasters and long-term environmental change goes together with lasting integration between border enforcement and military forces. For example, through its Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) branch, the Department of Homeland Security is the primary agency responsible for the security vetting of refugee applicants.300 USCIS makes the final determination on whether to approve resettlement applications, and its security review uses the resources and databases of numerous other national security agencies, including the National Counterterrorism Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Defense, and multiple US intelligence agencies.

- 267 Kälin, “Displacement Caused by the Effects of Climate Change.”

- 268 While centralized stocks of energy in coal fostered the labor control and exploitation that capitalism demanded, coal also empowered labor and allowed for a democratic mass politics to emerge. According to Timothy Mitchell, in the era of coal, “expertise” was at least in the hands of coal miners themselves, and governments became vulnerable for the first time to mass demands for democracy. Yet even this positive valuation of early fossil fuel exploitation falls through under the midtwentieth century development of cheap and abundant energy from oil. Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil, (London, UK: Verso, 2013), 42.

- 269 Mitchell, Carbon Democracy, 192–93

- 270 Jeff Desjardins, “The Evolution of Standard Oil,” Visual Capitalist, (November 24, 2017), https://www.visualcapitalist.com/chart-evolution-standard-oil/.

- 271Maria Kielmas, “Stages of Vertical Integration in the US Oil Industry,” Chron.com, accessed September 11, 2019, https://smallbusiness.chron.com/stages-vertical-integration-oil-industr….

- 272Alex Park et al., “A Brief History of Tax Breaks for Oil Companies,” Mother Jones (blog), (April 14, 2014), https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/04/oil-subsidies-energy-timel…

- 273Ankie Hoogvelt, “The History of Capitalist Expansion,” in Globalisation and the Postcolonial World: The New Political Economy of Development, ed. Ankie Hoogvelt (London, UK: Macmillan Company, 1997), 14–28, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-25671-6_1.

- 274 For example, although socialist states represent the intentional logics of socialism, much as labor unions and workers’ parties do, and although there has long been some coherence to transnational socialist movements and organizing, they have not been able to successfully create a fully institutionalized and global socialist socioeconomic system because the forces of the capitalist world-economy have shaped even socialist states so that they now play a functional role in the reproduction of capitalism. Christopher K. Chase-Dunn, “Socialist States in the Capitalist World-Economy,” Social Problems 27, No. 5 (June 1, 1980): 505–25: 1.

- 275Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2019), 198, https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520296640/ empires-tracks.

- 276 “Banking on Climate Change: 2019” (San Francisco, CA: Rainforest Action Network, March 19, 2019), https://www.ran.org/bankingonclimatechange2019/.

- 277“Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord,” The White House: Briefings and Statements, (June 1, 2017), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-tru…

- 278David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- 279In 2012, the last year of recorded data, nations in the Global South received a total of $1.3 trillion (including all aid, investment, and income) from the Global North. Yet, that same year, roughly $3.3 trillion left these nations—a net loss of $2 trillion to nations within the Global North. Since 1980, these net outflows have totaled $16.3 trillion, contradicting the widely held belief that the Global South merely drains the resources of the Global North through various sorts of aid. It is also worth noting that the greatest outflows have to do with unrecorded capital flight, with countries in the Global South having lost a total of $13.4 trillion since 1980. Dev Kar and Guttorm Schjelderup, “New Report on Unrecorded Capital Flight Finds Developing Countries Are Net-Creditors to the Rest of the World,” (Washington, DC: Global Financial Integrity, December 5, 2016).

- 280Wendy Brown, “Neoliberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy,” Theory & Event 7, No. 1 (2003), https:// muse.jhu.edu/article/48659/summary; Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014).

- 281 David Lloyd and Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonial Logics and the Neoliberal Regime,” Settler Colonial Studies, 2015, 1–3, https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2015.1035361.c

- 282Sassen, Expulsions, 55.

- 283Sassen, Expulsions, 88.

- 284Sassen, Expulsions, 84-85

- 285Sassen, Expulsions, 55.

- 286 “Nansen Conference on Climate Change and Displacement in the 21st Century” (Oslo, June 6–7, 2011).

- 287 David Suttie, “Rural Poverty in Developing Countries: Issues, Policies, and Challenges” (Rome, Italy: International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2019), https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/20… IFAD-overview.pdf; “Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle” (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018).

- 288“Nansen Conference on Climate Change and Displacement in the 21st Century” (Oslo, June 6–7, 2011).

- 289Boyer and McKinnon, “Development and Displacement Risks.”

- 290Norman Myers and Jennifer Kent, Environmental Exodus: An Emergent Crisis in the Global Arena (Washington, DC: Climate Institute, 1995).

- 291Fleming, “Climate Change.”

- 292 Lloyd and Wolfe, “Settler Colonial Logics,” 1.

- 293 Lloyd and Wolfe, “Settler Colonial Logics,” 7.

- 294 Elsadig Elsheikh and Hossein Ayazi, “Moving Targets: An Analysis of Global Forced Migration” (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2017)

- 295Robert P. Marzec, Militarizing the Environment: Climate Change and the Security State (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 1.

- 296 “Report on Effects of a Changing Climate to the Department of Defense” (Washington, DC: US Department of Defense, January 2019), https://media. defense.gov/2019/Jan/29/2002084200/-1/-1/1/CLIMATE-CHANGE-REPORT-2019.PDF.

- 297 Domestically, the Department of Defense provides disaster assistance at the request of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other federal departments and agencies. The Department of Defense always operates in support of civil authorities and is not the lead federal agency for domestic disaster relief missions, unless so designated by the president.

- 298 “2014 Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap” (Washington, DC: US Department of Defense, 2014), https://www.acq.osd.mil/eie/downloads/CCARprint_wForward_e.pdf.

- 299 Nick Miroff, Shane Harris, and Josh Dawsey, “Under Trump, Immigration Enforcement Dominates Homeland Security Mission,” Washington Post, (April 17, 2019), sec. Immigration, https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/under-trump-immigration-enfo… 6-5f8f-11e9-9ff2-abc984dc9eec_story.html.

- 300 “Refugee Processing and Security Screening,” US Citizenship and Immigration Services, (August 31, 2018), https://www.uscis.gov/refugeescreening.