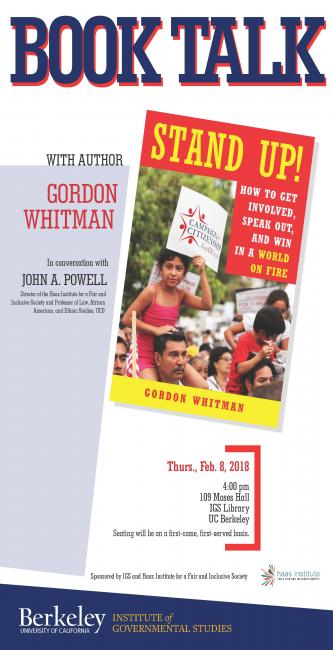

Gordon Whitman, the deputy director of the PICO National Network, soon to be called "Faith in Action," visits UC Berkeley for a chat with Haas Institute Director john a. powell on February 8.

The event, which discussed Whitman's new book, titled Stand Up! How to Get Involved, Speak Out, and Win in a World on Fire, was co-sponsored by the Haas Institute and the Institute for Governmental Studies.

The book is available in English and Spanish. To learn more about it, visit https://standupbook.org/

Transcript

john a. powell: Okay, so we're going to get started. We're starting a little late. So, first of all, thank all of you for coming, and those of you who don't me, you're out of luck.

Gordon Whitman: It's impossible.

john a. powell: My name is john powell. I'm Director of the Haas Institute, and in my family, I'm known as, six of nine, because there are nine kids, and I'm number six. Today, we're talking about Gordon Whitman's new book, Stand Up. Those of you who don't know Gordon, you're really out of luck. All of you know him or you wouldn't be here.

I've known Gordon for years as the head of, I guess, research and activity at PICO. I've worked with PICO for many years, and worked with Gordon for many years, and learned a lot, and shared a lot. I think we're better, meaning the researchers at Haas, because of PICO, and hopefully we've offered something there but more importantly, whatever we do here in the university in the research institute, we don't have, as they say, I hate the expression, "boots on the ground," because it's too militaristic, but we do need people who are actually engaged in community, and that's PICO.

Also, PICO's gone through a lot of transformation. To start off, I think, fairly orthodox, narrow focus ... And I'll talk about this in a minute because I think it ... then, they broke out of that, really stretching, having new alliances, having a new foundation, thinking more about spirituality, more about faith, which shows up in the book. It's interesting because PICO's a faith-based organization and like a lot of, PICO, [Camellia 00:01:57], [inaudible 00:01:59] foundation, they all come out of that tradition, but it's not central, I think, in terms of their practice.

So, the organizers are not, from my perspective, deeply animated by faith. I think my sense of Gordon and the work of PICO in last 10 years is that it's moved more in terms of that direction, and it shows up some in the book in some interesting ways. I'm just going to make a few comments, and then have a conversation with Gordon, and then hopefully, at the end, invite you into the conversation as well. I have a bunch of notes, most of which I'm going to ignore.

One of the things, when I was reading the book, and this is my second time reading it ... I read a early draft of it and then re-read it again. Those of you who know, Gordon talks about these conversations, and he takes us through, I think, the five conversations that are necessary for organizing, and building power, and face-to-face, and getting in touch with your emotions.

I must say, the overall gestalt of the book, and what he's doing, and when I think about the audience, I think it's a must read, and it's completely powerful. On the other hand, I think it, in some ways, still hems a little bit too close to what I would think of as the "Alinsky model." I think there's some tensions in there. For example, I'll give you one of the tensions. There's one, the intentionality of both a conversation and figuring out what your purpose is, and then when he talks about emotions and gets a little bit into the mind science, and sort of acknowledging that we actually don't have complete access to who we are, that who are is not immediately available to us. He talks about that more explicitly when he talks about our experiences.

He talks about our experience being mediated through stories, which I think is quite right, and quite powerful, and somewhat counterintuitive because a lot of times we talk about our experiences as if they're immediate, and that's the foundation of everything we do. So, there's a nice tension there. It's not resolved completely in the book. I was glad to see it there. I think that plays out in a number of different ways. Another tension I saw, again, I thought the grounding in contextual history, the chapter on inequality, was really wonderful. Especially because Americans, including organizing on the left, is incredibly ahistoric. We actually don't know about the GI Bill. We don't know about redlining. We don't know about these patterns, these structures, and I thought you did a really nice job of laying those out.

I think Gordon, from my perspective, avoided a classical mistake on the white left that is of privilege and class, over race, but he slips a little bit because you talk a little about how economic divide actually pushes into racial fragmentation, which is true often, but not always. It actually moves in both directions. There's a lot of literature suggesting that it is sometime the divide of race or ethnicity that actually causes economic divide, so it doesn't move in a single direction. You're going to respond to all of these things-

Gordon Whitman: Yes, [crosstalk 00:05:29].

john a. powell: ... when I give you the floor. The other thing I felt is that, the book, in some ways, privileged not only organizing but a certain kind of organizing. When I was reading the book again, I was thinking about, "Well, there actually is a revolution going on in the country right now. It's called, 'Trump,'" and Trump had a different model. He didn't do one-on-ones. He didn't do base building in the way that you described in the book. In some ways, I think what he did is he ... There's a book by Karen Stenner that I'd recommend to you called Authoritarian Dynamic. Her assertion is that a third of people across the globe are latent authoritarian, and it's latent, and it becomes active, interactive with our environment, and to use Gordon's term, very primed, and then it explodes. So, she says it's easy to activate and easy to de-activate, but it's not activated necessarily on one-on-ones.

There's a whole other process that can be activated and de-activated. One of the things I was thinking about is that the model for me is incredibly powerful, but it's a model, not the model. I would like to, either today or at some point, talk to Gordon more about what some other models are, and how we learn from them. Then, the last thing I'll say is that ... Well, two things, one the incompleteness of the organizing movement. In the sense that we've had a lot of victories, and Gordon talks to us about the miners, and about Fannie Lou Hamer, and [inaudible 00:07:14] but they're all incomplete. I would even say radically incomplete. I think in the book is, the way I'm reading it at least, you're calling for something more radical, and you're calling for not just a deeper movement. You're calling for what I call a [inaudible 00:07:32] movement. You're calling for a new self, a new we.

In that new we, I think we have to situate whiteness in a very critical role, not white people but whiteness. I think there's a phrase you use, which you basically say, "As long as there's inequality and a sense of scarcity, there will be fights around these different categories of whiteness in others." I think that's right, although I would frame it differently. I would say, the very concept of whiteness and dominance already has equipped into it inequality. That flows naturally from inequality, and Heather McGhee, actually I think, is one of your supporters in the book, talks about, if you have a position of privilege, unearned or not, then equality seems like an attack.

There are these tensions that are quite deep that you suggest in the book ... I was thinking along the book ... but you don't fully develop. Then, the last thing, and then I will turn over to Gordon, I really appreciated the personal stories and the story about his son, the story about his own growth and path. I think he made the book come alive, and I think there are lessons in it for all of us, even those of us who don't live our life day to day being organizers. So, let me stop there and have you come in, and we'll have a conversation back and forth.

Gordon Whitman: Great. Hi, everyone, how are you doing? It's great to be with john. We've been in dialogue for years, as john said. His imprint on both me, and the book, and on PICO, which is soon to be Faith in Action, speaking to your point about embracing faith and spirituality ... I also just want to recognize Father John Baumann, who founded PICO, soon to be Faith in Action, 45 years ago and works out of Oakland and started in Oakland. So, it's great to have you here, john.

I think the starting point place to sort of respond is I do feel like we are in a struggle. It's almost like a race against time, but I think humanity is getting better. I think there is something happening around, and I look at my own kids, and their friends, and just sort of what's moving in the spirit. I think there is a greater sense of connectedness of ... You know, in some ways climate change, I think, brings it to a really sharp point that we're in this. We're in this very small, little planet spinning through the universe, and the idea that we're sort of on our own individually responsible for somehow creating good lives or creating a better world just makes less and less sense. I think there is a sense that ... I feel like we are getting better at the same time that we're facing up against a set of vicious cycles that are driving our politics, and inequality, climate change, migration, racial anxiety. So, I think most I'm trying to write into that tension.

When I wrote the book, I had this idea, and I've been arguing with people in the publishing business from the beginning that I kind of wanted the book to be in the self-help section. I don't know about your book stores, but where I live in Arlington, Virginia, my Barnes & Noble, there's like a quarter of a shelf says current affairs, and it's got Rules for Radicals by Saul Alinsky, who's not mentioned in the book at all anywhere, by the way, but obviously the tradition is certainly in there. Then, there's like a wall of living your best life. Right?

I was really interested in not writing for an intellectual audience but really writing to the end of action, of engagement. My sense is, through my work as an organizer and just being alive right now, that there are so many people out there who are frustrated and angry about what's happening. You see it on their face [inaudible 00:12:25]. They see it in their own lives. They're experiencing it personally, whether it's, "I'm worried that my child can't go to college or afford college," or, "I'm afraid that a family is going to be deported," or, "I have a criminal record." A third of Americans have a criminal record, and there are so many barriers to getting work and finding housing, so personally, and then in the media and what we see in our friends and community, but aren't quite sure what they can do about it.

And john, you said, and it certainly stuck with me a lot, that most people, something like 90% of people, think there's too much money in our political system and that it's corrupted the political system. The problem is most of them don't think anything can be do about it. So, do we spend our time trying to persuade the last 10% of people that there's too much money in our politics, or do we figure out how we can begin to do something about it? You look at what's happened in Seattle and Portland, where you had local ballot measures ... because it's really hard to change the political rules through the political system ... ballot measures that passed and created finance systems that give people vouchers. So, you live in Seattle, you get four $25 vouchers, and if you're running for office, you can aggregate those if you participate in the system, and it really goes from a system where a tiny number of people are financing campaigns to, "Here's another way you can participate beyond voting."

So, it takes a long time, but that's the sort of vision of ... We've got to start there, and it's sort of the history of American politics. We have a constitution written in so many different ways by primarily white male slave owners to keep the status quo in place, and we're still living with that constitution that we revere but makes change very difficult in Washington. So, we complain about Congress, but it's a long history complaining about Congress being an entity that doesn't do much, but it's designed that way. So, the history of starting local really matters, but people have to believe not only that change is possible in a society that's so built on individualism and you can't fight city hall.

So, even in our organizations, even people who think they're progressive, I think, we still assimilate this notion that we're pretty much on our own. I talk about in the book that one of my formative political experiences was living in Chile in 1990 at the very end of the Pinochet dictatorship, and you know, one thing going to meetings where you realize that people were ... it's life and death, right? That was helpful to think about what politics means and that you have to trust people. But the level of political consciousness was incredible and formed over generations of political parties and organizing that prepared people to be political. And I think one of the biggest challenges we have right now is not being political enough as a society. So, we're facing this incredibly well-organized and scary attack on democracy and attack on basic rights. You've got leaders of the immigrant rights movement in this country who are being detained and deported solely because of their political beliefs as one tip of the iceberg of what happens when you speak out and get involved with change.

So, we're facing a very serious political moment with a society that's fairly de-politicized. The question of how you do this on scale is, I think, a big question. The organizing tradition I come out of has ... faith-based organizing usually is how it's identified. Organizing more broadly, what attracted me to it, I was on my way. I went to law school, and I was on my way to being a lawyer for community organizations. That's what I thought I would do. Then, I went to Chile, and I saw a social movement, and I thought, "Oh, what is that in this country?" How many people have lived outside of the United States and experienced a level of social movement activity or a different kind of politics than our political expectations?

Audience: Raise your hand.

Gordon Whitman: And it shapes how you look at the world. So, I came back, "Where do you find that in the United States?" The closest thing I could find was faith-based community organizing, but as I was taught it, it was a tradition that said, "Do multi-racial work, but don't talk about race or too much about race because you'll make it harder to bring people together." In fact, I think it made it harder to actually build trust. Then, if you're not fighting both race ...

You know, we were doing this big campaign in Pennsylvania to create a fair funding formula for the state. It's one of four states that doesn't have any school funding formula, so the politicians just decide where the money goes. And there's a whole infrastructure built to create equity across school districts. That campaign never did a racial analysis of what would happen if you eliminated the economic disparities. Our organization Power, which has built into it a racial consciousness and an understanding, "Whatever issue we're going to work on, we're both working to expand the pie, create opportunity but also close racial disparities," said, "Well, why don't we look at, in addition to economic disparities, what about race?" Even if you eliminate all the economic differences, there's still a curve based on the percentage of African-American students in the school district and how much money they get from the state. But that's not how I was brought up in organizing.

We also had tradition pretty much focused on self-interest. john has worked us, and this is a little aside that I think if anybody is in the university world asking, "How do you make a difference?" john is such a great example of the ability to do it all at some level, not everything, but to both be deeply embedded in social movement organizations. I've seen people who know john just not, "I'm going to go speak somewhere or do research with a group," but like a lifetime commitment to walking with organizations. john's investment in PICO, Faith in Action, the larger movement just is ... People can send something that we're working on, like a statement. "john, can you take a look at this and see if we can word it differently so we're really not reinforcing bad narratives?"

So, that level of commitment to being in solidarity with and in partnership with a movement, and both give to and receive from so tremendous a, I think, role model of what it means to be a public intellectual. And one of the things john's worked with us on is, "Well, self-interest's important. Organizing's really based on it. If we're going to build movements that people are part of, they need to see themselves in it." It needs to ... What I say about PICO or Faith in Action, we're successful if people can say, "My involvement made a difference in my life." So, my participation in this organization, open community organizations, or PICO California, or ISAIAH in Minnesota, "I can see something better in my life as a result. Might have helped someone else, but I can identify something in my own life that's better, and I look at myself and the world differently." If we can hit that sweet spot, then we're really adding some value.

We can be involved in lots of things that make life better for other people. We can be involved in things perhaps that are better for ourselves, but are they transformative? We're trying to create experiences that really transform people. So, self-interest's important, and I've been baked, this has been baked into me over the last decade, in large part helped by john. You know, we're really motivated by our emotions, by our search for purpose and meaning, connection, and I think we've become much more expansive about the kind of organizations we build, what we do in rooms together. We really should be doing some organizing in this room. We sort of started off without doing it. But we're really trying to create emotional spaces where people feel valued, and their voices matter, and their stories matter, and that that's the foundation in building more humane organizations.

The question is, can you do that at scale? I think that's where we have not answered. Can you build social movements that are people centered at scale that are large enough to go up against the Amazons and the other multinational, global institutions that really are increasingly running our politics? I don't think we've really answered that question. But I was really trying to write a book that was less about a set of ideas and more about a set of practice.

But embedded in it is a theory that says that people don't learn politics and become politically conscious because somebody tells them about what's wrong in the world. People don't feel powerful because somebody tells them they're powerful. It's through experience embedded in meaningful activity with other people, and the people we think how the world works and become political. Our organizations need to be racially conscious. They can't segregate that work of this organization does anti-racism work; this organization works to raise wages. We've got to see those as interconnected fights. It's helpful to think about, as much as we head there, the segregation of the activity is so deeply embedded in American society and in our social movements that it still lives on. You feel like you kill it, and it comes back up.

Then, these organizations need to be more humane. The tradition, that Alinsky tradition, the tradition of treating people as ends and not means, of experiencing somebody somewhere saying, "I organized an event; I need you to come to it," or, "Would you sign a petition?" I'm re-reading ... How many people have read No Shortcuts by Jane McAlevey? Okay, so this is a book to read. So, after you read Stand Up, there's one book, this is one book that I'd read next to it would be Jane's book No Shortcuts. It's really a deep, deep critique of the labor movement. As much as labor movement is suffering from external attacks, the abandonment of organizing, of working with workers to build their capacity to go on strike, to withdraw their labor, is like a lost art in the labor movement. There's lots of shortcuts and lots of things you can do, but fundamentally, peoples' capacity to live a decent life and to negotiate at their workplace depends on their ability to successfully collectively withdraw their labor. She's got some great, very practical stories about how organizing can happen in a way that people build that capacity to use their labor to negotiate what they need.

One of the things she says about community organizers, you can never say thank you at the end of a visit. So, organizer visits a worker at their home and is trying to challenge them to become part of a union organizing campaign. The good locals trained their organizers, "You may never say thank you," because you don't want to create the union as a third party to a negotiation, which is what most workers experience. "I have an employer, and I have a union, and then there's me." Really, it's, "There's an employer, and then there's a union, and I am the union."

So, that's sort of the spirit we're trying to teach, but doing that at scale. The last thing I'll say is that part of our challenge is that even among organizers ... So, [inaudible 00:25:24] is a colleague deeply influential in my thinking, did research among labor organizers, and a fraction of the time that labor organizers are spending during the week is with workers. We probably ... I don't know the number. We might have 50,000 people who are paid to advance social justice in this country, and the question I was asked is, "How many of them are talking to people who aren't also being paid?" So, we've really professionalized the sector, but we haven't really built a movement, so I have a ... What I find is like quantity over quality in some ways.

We really need to democratize political activity and make it much more part of normal life as much as anything, and that's really part of the story of the book. What I'm excited ... We put it out in Spanish, too, so that it's really sort of trying to get it out there into the world. So, there's my response. I think I answered every challenge.

john a. powell: I have one more round, and then we'll have you respond, and then we'll open it up to you. A couple things. I was very ... First, I was reading the book, and I would go read it again at least a third time, maybe a fourth time. At one point, I was feeling like the organizing in the book was organized for outsiders. So, in that sense, it was talking about ... It was interesting to me because it was like powers that be, like city managers or heads of banks, which I don't think is really very powerful. I think they're transactional. You know anything about banks, banks are actually being driven by hedge funds. They don't actually make decisions themselves, and no one meets with hedge funds.

So, in a sense, the one-on-one meetings with people in power, I felt like, "Those aren't people in power." They're actually ... But anyway. At the end of the book, you get to this because like who made the rules? Most organizing ... Again, you do get to it at the end of the book; I probably would have put it a little earlier ... is actually changing the rules. You talk about a chess game and changing the environment. We're seeing that now but a deliberate strategy to change the rules, not the strategy to win by the rules, but to actually change the rules, and that's, to me, much more transformational. So, I'd like you to comment on that.

Next week, I'm going to Oregon. Some of you may know, [Derrick Bale 00:27:56] was the dean of-

Gordon Whitman: He was my teacher.

john a. powell: He was the dean of Oregon, and he got canned, essentially, because he pushed too hard for bringing black faculty to the University of Oregon in Eugene. It's interesting, an interesting story. Derrick was a good friend of mine, although we didn't agree on everything. I'll come back to that in a minute. But he was being considered, he was being vetted for, a MacArthur Genius Award, and everything is secret. They swear you to confidentiality. So, they called me about Derrick and said, "You know, he's done all these incredible things, but when we talk to people at Oregon, they said he was kind of a ... he fought them too hard." And I said, "Yeah, that's not the issue. What was he fighting for?" He was fighting to bring more people of color and women there, and he lost that fight. But now he's being penalized 10 years later like, "He came here and caused trouble." So, I'm going up to Oregon, and they're still fighting the same fight.

But one of the things that I'm on record for disagreeing or challenging Derrick about is he talked about interest conversion. That's one of his things that he loved with critical race theory. The [inaudible 00:29:00] interest conversion from our perspective as Derrick talked about, and to some extent our organizer talked about it, that Gordon's already prefigured, is that interest is seen as given. Interest is actually situational. Our interests actually change. You change a person's situation, you change their interests. I can give you a concrete example. Think of the work around janitors in Los Angeles, and what the union finally figured out was that if they brought undocumented workers into the union, the union no longer opposed undocumented workers. So, on one hand, it's like you're now analyzing this, but you're analyzing it on a set of conditions. You change those conditions, and your interests actually change. So, interest is actually not that stable.

Again, going I was glad to see in the book, just sort of suggested, the multi-faceted nature of who we are. We're not stable people. To some extent, that's an incredibly radical thing that if you could hold onto it, I think it moves us in some interesting ways. Two more things, two more other points. One is when I was reading the book, and I don't know exactly why, but death came up a lot. To paraphrase Mark Twain and Reverend Doctor King, they both say something like, "If you don't know what you're living for or want to live, if you don't know what you'll die for, you have nothing to live for." Somehow, that just ... For some reason, the book reminded me of that. I don't know why exactly.

So, I think there's these deep tributories in the book that actually radically change the way we think about organizing. One of my favorite writers, Roberto Unger, he says, "A good life, you only have to die once." I mean, we all have to die, but we don't have to die every two days. So, part of dying once is having something to live for and being in deep relationship, being part of something. Those of you who have heard of me have heard me talk about my dad many times. My dad is 97 years old, and he's been ready to die for years. We have a deeply connected, interconnected family. About 12 years ago, my dad was diagnosed with this life-threatening tumor. He called the family together because we make decisions collectively, and he said, "I'm not going to do anything. At this point, I'm 85 years old. My wife has passed. All the kids are grown. I'm ready to go." You know, announcing it, but also gently asking for permission.

By the way, five years earlier he had a similar episode, and he was in the hospital, and he said at that time to my mother, "This is too painful. This operation's too much. You know, all the kids are grown. I'm ready to go." And my mother said, "No." He asked her permission to go, and she said, "No." Next, he said, "No, honestly, this is so painful, I can't stand it." She said, "Stop being a big baby. You ain't going nowhere." This time we didn't have that kind of cache as my mother, so we couldn't say that, but what I did is I did some research and found out that the tumor he had could actually explode and not kill him but completely incapacitate him and leave him in deep pain. So, he said, "Okay, I'll have the tumor removed."

But the point is is that it was a collective decision. For him, there was no reason to stay here. His life was complete, and he believed ... He's a Christian minister ... he believed that God keeps us here for a purpose. I said, "Okay, dad. You're 86, 87," at that point. "What do you think God's keeping you here for?" He said, "I think I'm here now to teach the kids how to care for other people." His whole is ... And I'd like to think my life, too ... is about deep connections with others, and so the spiritual grounding, whether it's a relationship to God, or to others, or to community, and I think being deeply connected to my family and larger community, the fear of death is largely non-present. I'm not saying it's completely gone.

Last story on this. My daughter had a daughter, so I have a granddaughter, and my daughter's very close. Some people accuse her of being her father's daughter. But when my granddaughter was born, I told my daughter, I said I felt like the circle is complete. You know, I'm not trying to leave here, but it's okay now. My daughter said, "Not okay. You got to stay." My point is is that all those things are part of the book, and I guess the last challenge I want to make to you, Gordon, and to all of us, is that when you read Karen Stenner, she argues that authoritarian values and liberal values are almost an exact opposite. Authoritarian values are about obedience. They're about obeying the law. She has three, and the last one is sanctity, which is cleanliness. They don't believe in equality. They believe in equality. They believe in social dominance. So, a lot of things that we think people organize around, they don't.

Up until 10 years ago, only 15% of the population consciously identified with the social dominance. 85% of the population identified with some form of equality. That number has shifted now. They're now 30%, almost all white, now believe in social dominance. So, they believe that whites are supposed to dominate. So, I guess one question is how do we actually ... And the number's probably growing. Like you suggested in terms of priming, we'd like to shift that. But how do we talk to people who start off by believing, "I have a right to dominate women. I have a right to dominate gays. I have a right to dominate blacks. I have a right to dominate"? The question of connection, the inner connection is fine, as long as one white person to another white person. "Okay, we can connect, but I don't want to connect with immigrants. I don't want to connect with gays. I'm willing to connect with women, but only within a subservient role." How do you think about ... I mean, do we just write those people off? Because 30% is a lot, and they're well organized. So, Gordon.

Gordon Whitman: Yeah. I've been reading a little bit about the Russia post-Soviet Union collapse, and there's a lot of polling of the rise of authoritarian thinking over time. So, clearly, it's something that's being done to us and that we're fighting against. I believe we can overcome implicit bias and authoritarian thinking through relational work, but can we do it at scale is a question that Joseph McKeller and Ben McBride, who lead PICO's work in California, have been traveling around the state. They just became the co-directors, and they've been traveling around the state talking to grassroots leaders, and the question they've been asking people is, "Well, if you put aside what we should do, what do we want to become, and what do we want to be?" I think that's in the spirit of sometimes we don't ask the right questions about ...

I think the left and progressive group, and the people striving for social justice, probably are spending too much time asking the question of, "Well, what's the right strategy? What's the issue we should work on?" We're not actually creating a movement that people can say, "Now, I want to be a part of this because it's meaningful to my life, and I can see myself in it." I've been in California now probably nine times over the last two years, and I've spent almost all my time in the Central Valley, so I've been in Fresno, and Merced, and Bakersfield, and PICO's had five organizations in the Central Valley for the past probably, I don't know, john, 20 years or so. john probably, you probably created them at some level, in Stockton, Modesto, Fresno, and they're great organizations.

The Fresno group has been in this tremendous fight over creating a housing policy in the city of Fresno, so really good fights at a city level, but when you look at the Central Valley and how it's organized, the ag industry, realtors, transportation, the people with the institutions that run the valley, and I guess you're saying there's, behind that, a set of forces of capital that are financing and are all organized at a regional level. The challenge has been for human beings who've been invested in their local organizations, how do you create something that has a regional vision, that has regional power, that can ... The air quality board basically runs the Central Valley at some level, or through the air quality board, economic forces run the Central Valley. How do you ... And it's really the opposite. It should be called the bad quality, a bad air, because it's all organized to basically facilitate pollution. How do you organize at the regional level? We've been through this big process of ... We actually ... All five organizations decided to merge into one Faith in the Valley organization and then create chapters.

So, you talk about death. What I've learned from organizing is that a lot of times, an organization has to die for something new to be filled up, and it's very hard. It's why we're full of organizations that have lost their way and their mission because it's almost impossible to kill an organization. In fact, I think sometimes the less effective it is, the more likely it is to succeed.

But we've been through this interesting process of developing a regional vision for the Central Valley and a vision of what it would mean to be one valley and create. Essentially what people have said is that the biggest narrative question is, "Can something be different?" Is it possible for the Central Valley to be different, or does it have to be this way? Then, there's the question, "Is it the air quality? Is it getting control of the county governments because that's really where the power is?" So, there's a lot of practical questions, but it's been amazing to me the willingness of people from Bakersfield to drive all the way up to Stockton every two months or so for a region-wide meeting and that the Central Valley has an identity.

So, as an organizer, it's easy to go to the theoretical questions, but practically, how do you do that? How do you create an identity that's a new identity that has a political significance? Because if people don't feel like they live in the Central Valley, but the forces that are operating and reshaping their environment are operating at that level, it's such an asymmetrical question. I think a lot about, is organizing enough? I think it's an element, and I think we need to do it better. We need to operate at so many different levels. So, that's it, but I appreciate the challenges. I think it's incredible.

john a. powell: I'm going to open up questions, and as I do so, I want to acknowledge Olivia, who does our California work around narrative. We just did a survey. Is it open to the public now?

Jeff: It can be. If you reach out to me, I'd be happy to share.

john a. powell: Okay.

Jeff: It'll be published in the [crosstalk 00:41:11].

john a. powell: It look at the Central Valley. It's looking at who Californians think they are, and what's the divides. One of the things they found, the survey, if I'm not mistaken, is that the economic divide was much smaller than the racial and immigration divide, which also tells us where we need to do work, what's actually separating people. Just one other footnote, we did a study that the state adopted for housing statewide, and Wiener actually has a bill in the Senate now to build more affordable housing and mixed-income housing along transit stops, and not to let cities and counties override that rule.

The progressive mayor of Berkeley said that this proposed bill was war. The point I'm making, Gordon has said, he was saying cities have a right to control their own destiny, so this sort of fragmentation. So, every city should have a right to say, "Not in my city." So, where do you build housing? And he's coming off as this progressive mayor. It's like, "We're going to fight this to the death." It's like, "Really?" Just in the Bay Area ... Those of you who live in the Bay Area, most of you probably do ... in the last two years, the Bay Area has created almost 500,000 jobs, and we've built 50,000 units of housing.

So, the growth of the area and people coming in come in with more money than people already here. The dynamics is that that's going to keep driving up the cost of housing. Then, we have this progressive mayor saying, "The city has to control its own city," as opposed to, "This is a state problem. This is a regional problem." You know, anyway. Let me open up for your questions and comments now, and tell us who you are.

Jeff: Jeff [inaudible 00:42:56]. Bill Moyer, Building Democracy. I didn't see ... Oh, you've never heard of it?

Gordon Whitman: No, Bill Moyer, I think all of us ... Or, I won't speak for john, but the tradition of democracy ... I know the court system's important. I thought what we're trying to do is recapture democracy, and some of that is in the life of organizations so people have the experience-

Jeff: So, my question is about chapter four. It's about activists' self-sabotage. I've just never seen anything so spot on, unless you've seen Monty Python Life of Brian, but I mean, it's so spot on and what happens in self-sabotage, and I'm wondering ... I don't think I saw that in your book, and do you think it's relevant, or ... Do you know what I'm talking about?

john a. powell: Just a little bit of context for those people who haven't seen it, what's in it that you're asking? Because a lot of people haven't seen it, so they won't understand the question.

Jeff: Self-sabotage?

john a. powell: Yeah, what do you mean by that?

Jeff: What do I mean self-sabotage?

john a. powell: No, we know self-sabotage, but what's an example? What do you [crosstalk 00:44:16]?

Jeff: So, what I mean by self-sabotage is everybody is so certain that we live in a sue-happy society, and the number of lawsuits is climbing, but the number of filing fees is down so dramatically that all the California libraries funded by them are going bankrupt. It's down like 40% in six years. So, why is nobody in the activist community ... They're just completely, as the [inaudible 00:44:43] movie documents, they're misinformed. They're stigmatized. It's worse than misinformed because they believe what [crosstalk 00:44:51].

Gordon Whitman: We had a chance to talk beforehand, and I think just to share with other people, right? So, the question that we at least talked about before is are we using the court system adequately to advance justice, or are people discounting what can be accomplished in the court system? As a lawyer turned community organizer, I think it's a fair question. I mean, we need a mixed media strategy to social change, and I would say, from our field, we probably underestimated the ability to use the legal system to accomplish goals, but I think in part because, as a former legal service lawyer, I think that set of institutions, whether it's law schools, or legal service, or civil rights organizations haven't always been prepared to partner. I think there's a question there about how we do a better job partnering between advocacy groups, legal groups, organizing groups. Not everybody coming from law schools has such an embedded relationship with the organizing movement. Other ... Yeah.

Audience: I just wanted to comment on that. One of the organizations that-

john a. powell: Tell us who you are.

Lisa: Think of ... Oh, I'm sorry. My name is Lisa [inaudible 00:46:06], and I'm a retired judge. The League of Women Voters just had a huge success in Pennsylvania, and in Kansas what they're doing is they're partnering with the prison system when parolees are getting out, and educating them about their right to vote and how they implement it. So, they're doing things that you might not associate with the League, but they're open to partnerships.

Gordon Whitman: In Florida, we're partnering ... Faith in Florida, our Florida organization, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, which is led by formerly incarcerated returning citizens ... partnering League of Women Voters, ACLU, other groups. They have now put on the ballot in 2018 a constitutional amendment that would re-enfranchise somewhere north of 1.5 million Florida residents who are prohibited from voting. One out of 10 people in Florida can't vote because they have a criminal record, one in four African-Americans, tremendous. It's interesting because ... john's done some consulting on it ... we have to persuade 60% of Florida voters to re-enfranchise 1.5 million people. The polling and the focus groups are fascinating, and I think they point to what the path forward is.

The original messaging framework for the campaign was about voting rights and about democracy. So, it was actually incorporated as Floridians for Fair Democracy. Then, we went out, and we talked to people with the eye towards you have to persuade 60% of people who vote to say yes on this amendment. What became really clear was that you could not get to 60% of the vote if it was a conversation about politics. You were just going to be 50-50. But if you talked about second chances, redemption, you get to 65, 70%.

john a. powell: You even got Trump.

Gordon Whitman: You even get Trump, right. Trump's talked about it. So, [inaudible 00:48:10] I think you can start to tap into the business side of the sort of, "Well, we might end up going to jail ourselves, and these regulations are too strict." I almost feel like these governors who are about to go to jail suddenly become very firm against the death penalty. They have this last-minute conversion about criminal justice reform. We know the Koch brothers are a big financier of ending mass incarceration because they have a set of agendas around decriminalizing corporate activity.

But it's an interesting sort of like ... I think what that points to is both the structural questions of we have to fight for democracy. I say to people inside of our organization that if you're at a meeting, you've got to ask three questions if you're doing strategy. One, "What are we doing that would deliver real benefit to the people that are in the room and that are our base?" We can't lose touch with what our people need. Two, "How are we changing the rules to make it easier to fight the next fight?" Are we going to same-day registration for voter registration or re-enfranchising formerly incarcerated? Are we opening up more voting sites? All the things that make democracy work. Three, "What the story we're telling?" Olivia's helping us with in California. How are we telling a story that people want to be a part of? It's easy, I think, and we're built in so many issue silos to not do the second two.

john a. powell: So, we'll take two questions. Well, I see three hands, so I'll you three ask questions, but I ask Gordon to wait until all questions [crosstalk 00:49:48]. Then, you'll answer those questions and make closing comments, and then we'll let you go. If you need to leave before then, that's fine. So, I saw one, two, three.

Adena: You first. No. [inaudible 00:49:59]. Me? Oh, okay. She's letting me go first. I'm Adena, I'm president of the League of Women Voters of Berkeley Albany, Emeryville. Something that I really struggle with when I've done organizing and as I do organizing is what is my issue? What am I allowed to work on in some ways? The League is kind of easy because, you know, voter registration, democracy, that's very broad. I think that affects everyone. But something I struggle with as an individual is kind of saying, "I want to be part of this issue. I think it's really important, but it doesn't affect me." I want to support but not be in a space that it's not my area of expertise and put myself into a space that might not want me. Besides the obvious of asking and seeing how you can support, do you have any thoughts on that? That's my question.

john a. powell: Okay. Next question.

Audience: Is it me?

john a. powell: Yeah. I think it was you.

Audience: Okay. Another League of Women Voters person here, and one of the things that I'm concerned about is the way we express things is very abstract. We don't tell stories, and that makes this topic hard for us to connect with people because it's too school bookish. That, plus the fact that we're not sufficiently racially diverse, a lot of our leagues. It varies, so we try and partner with more diverse organizations, including [inaudible 00:51:29] right here in Berkeley. But it's a real dilemma for us when we want to really change the League from white suffragists from actually 1911 in California to a much broader palate of all of us.

john a. powell: Yes.

Audience: Hello, I'm Dax Vivid, and I'm interested in that question of scalability and your thoughts on new media, or social media, and the Internet as a ... if that's even a useful tool or if really in person is the way to go.

Gordon Whitman: Yeah, so in some ways, they're all connected questions really. I don't want to generalize, and I've been doing a lot of radio interviews as part of this book tour promoting the book, and I think there is a challenge on the left of being too issue focused, too lecturing, too much talking at people and not with people. So, I think we need, given the stakes, we need to build organizations differently, so the racial consciousness and just building it in, and the sort of [inaudible 00:52:47] in places and listen in proximity. I feel like we are all obligated to build better organizations that are more humane, just like this simple thing. This is the first book event that I've done where I haven't spent the first 10 minutes asking people to turn to each other and share their story. I felt bad about that right now.

But I really think simple things that shift the emotional state of the room and the world ... I really have a big ... increasingly a believer in our capacity to create a different emotional environment with our own being and our willingness to ask questions and take risks. I think the risk taking, like we are not taking big enough interpersonal risks across difference because we're much more connected. I think we can ... I love Facebook. This helps me connect to people that are so far away that are important to me.

I think it's more the content than the methods and that we can create different kinds of more humane content. I guess my ... I'll talk a second about the book, but I think one like, if there's over the next couple of weeks a meeting you can go to that you haven't been to, or if you're in something, is there something that you could do to either take on more responsibility or to create a more humane environment in the organization you're in? I'm really a believer in small steps and ripples, I would say.

And then, just on a really practical note, basically Berrett-Koehler, which is open-based publisher, published the book in English, and then the California Endowment helped support the translation into Spanish, and that I self-published. They're both available in ... Well, the English book, it's available in book stores, less so the Spanish one. They're both available on Amazon, and then I'm selling them back in the back of the room with cash or credit cards for either the Spanish or the English one. The Spanish one's $8 because it doesn't have a middle man. The English one is $12, which is basically the cost. There's also an audio version on Audible, and there's a website www.standupbook.org because nothing can happen without a website. Yeah, I really appreciate being here.

john a. powell: So, in closing, let me say two things. One, I thought about what you said, Gordon, which is how to organize the room, which we didn't do, in part because we started late. So, I'm going to suggest that as you leave, after you buy the book, you can grab someone just on the way out, and what Gordon talks about in the book is about emotional connection. See if you can emotionally connect with someone by telling them a little about yourself, what's important to you, but also listening. So, just say five minutes, do that.

Just as an ending by saying I really have felt really a great privilege to part of the relationship with PICO in general, but Gordon specifically. Gordon talks about trust, and for me, there's genuine caring and love for Gordon and his life's struggle but also a tremendous trust. So, even if we don't agree on everything, which we almost do, I really trust just the basic openness and integrity that you bring to the table, so I want to thank you for sharing with us. Hopefully, you can buy the book. I'm sorry. I have to run. I have another appointment at 5:30, so I won't stick around, but thank you for coming and thank Gordon.

Gordon Whitman: Thanks, john.

Gordon Whitman has worked as a community organizer and social change strategist and coach for the past twenty-five years. He first learned organizing in Santiago, Chile, and helped found successful grassroots organizing groups in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Flint, Michigan. As the deputy director of PICO National Network, the county’s largest faith-based community organizing network, he has coached hundreds of organizers, clergy, and grassroots leaders. He’s been responsible for PICO's expansion program, helping people of faith and clergy build some of the most effective new multi-racial community organizing groups in the United States over the past decade. Gordon has led national organizing campaigns on children’s health coverage, national health reform, and stopping of foreclosures. Before becoming an organizer, he worked as a legal services and civil rights lawyer in Philadelphia. He has also been the associate director of the Temple University Center for Public Policy. He’s written dozens of policy reports and articles on social change and regularly blogs on Huff Post. He has a law degree from Harvard Law School and an undergraduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania in history and urban studies.