WHAT DO PURINA DOG FOOD, CHEERIOS, DORITOS, AND AQUAFINA ALL HAVE IN COMMON?

They’re all owned by Nestle. While Nestle is most famous for its chocolate and coffee, it actually owns over 2,000 product brands in various industries, from cosmetics (L’Oreal and Maybelline) to high-end fashion (Armani and Ralph Lauren) to baby food (Gerber’s).

Over 2,000 brands. And that’s just one corporation.

In reality, there are a handful of transnational corporations, including Nestle, that control our global food supply. These corporations have the power to manipulate every aspect of the system—everything from production and distribution to labor conditions and lobbying governments and legislatures.

To have so much power and capital in the hands of so few... well, it’s a recipe for disaster.

This spring, we partnered with Elsadig Elsheikh (Haas Institute’s Global Justice Program at UC Berkeley) to create an illustrated video for the Shahidi Project. The Shahidi Project is an online investigative database that illuminates the concentration of power between the 10 largest food and agriculture corporations in the world.

The Shahidi Project reveals important truths about power, corruption, and inequity in our food system.

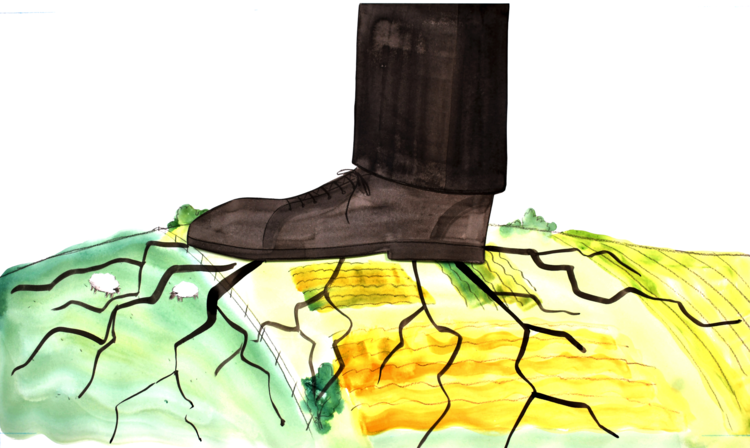

THE SCOPE OF CORPORATE POWER IS DANGEROUS

Corporations rely on industrial agriculture to control global food production and consumption. Industrial agriculture produces food on a massive scale, but its effects are devastating—it’s one of the leading causes of global warming and environmental degradation. It also ruins the local economies of small and mid-sized farmers.

While you might think the point of industrial agriculture is to feed the global population, the truth is more complicated. There is more than enough food to go around, but the world’s poorest continue to suffer from hunger and food insecurity due to high prices and inadequate access. Solving this problem is possible, but presumably it’s not profitable enough for corporations to pursue.

At the end of the day, these giant food conglomerates prioritize profits. Not marginalized communities, or the environment, or labor rights. So the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer (and hungrier).

Sounds like the plot of a dystopian novel, doesn’t it?

“BUSINESS AS USUAL”

Obviously, not every consumer has the time or energy to research all the mergers, acquisitions, lobbying, lawsuits, and backdoor deals that compose our current food system. Even if they did, these corporations hide their dirty laundry very, very well. They make their paper trails purposefully entangled and complex, disguising corruption as “business as usual.”

In other words, it’s a hot, convoluted mess.

THE SHAHIDI PROJECT EXPOSES HIDDEN POWER STRUCTURES

In Swahili, “shahidi” means “to bear witness,” and that’s just what the Shahidi Project does. Through simple visuals and accessible language, the Shahidi Project demystifies how these corporations influence (and operate) the global food system.

Reading through the Shahidi Project website feels like reading a top-secret government document. Did you know that in 2017, PepsiCo and Nestle were accused of illegally destroying rain forests in Indonesia to create palm oil plantations? Or that Monsanto has been linked to over 300,000 suicides of small farmers in India since the mid 1990s?

True to its name, the Shahidi Project lays the truth bare. From the start, we knew this was an important story to share with the world. The Shahidi Project has pushed us to think critically about who produces food, who profits from consumption, and (most importantly) who gets left behind.

To learn more, visit the Shahidi Project website here.

Editor's note: The ideas expressed in this blog post are not necessarily those of the Haas Institute or UC Berkeley, but belong to the author.

This blog post was originally published on the website of RogueMark Studios here.