Sandy Storyline, photo by Josh van Pragg

To clarify; we are not asking artists to solve a global crisis of climate forced displacement. We also do not expect artists to formulate ‘plug-and-play’ solutions for use by organizations, lawyers, activists or others. This said, artists are essential to addressing the many problems entangled with this issue. But what role will artists play?

The larger point that the Artist Circle addresses is how artists work can help numerous sectors rethink, shift and expand practices. Artists will continue to inspire and compel action. This remains an important part of our work and often the basis of our praxis. But the methods, skills and analysis developed through artistic practice are unique and, like so many movements before, will play a key role in the future of this work. With a bit of flexible thinking and willingness to connect the dots, artists can contribute greatly to broader, multi-sector efforts to address climate-forced displacement.

For example, artists’ inquiry processes are frequently roving, porous and emergent, which helps us note new arrangements, think about the interconnection of histories and events, and create meaning through multiple registers of witness that reflect the totality of life (affect, material, spiritual, quantitative, symbolic…). In the Artists Circle, this meant that we restlessly returned to discussions on the many roots of climate forced displacement, its varied effects - whether direct or as ripples, and what is lost or gained in the different framings. It compelled us to think about the interplay of issues and elements related to climate displacement such that we were not only discussing making work about “climate forced displacement”. Instead, the group is making work about interspecies communication, supply chains, community-led redevelopment, the histories of sugarcane plantations, healing justice and more. When we only discuss climate forced displacement as an issue of people being forced to move due to climatic events and changes, we lose many things, not least is an understanding of the total picture of what we lose through displacement, which is crucial for understanding necessary resources for rebuilding, adaptation and resilience, and the ability to identify pressure points in creating larger systemic change.

Another example: the members of the Artists Circle have strong principles and ethics tied to storytelling; Why are we telling a story? Who is telling the story? Who benefits or loses from telling the story? Who has the right to a story? What are the dynamics of power in the distribution of a story? How does the story’s form change how we understand the story? In discussing legal approaches to creating a climate refugee status, numerous questions surfaced out of our experiences in storytelling. Refugee status is largely individualized and must be proven; in effect it is a story told for the legal validation of experience. This can be retraumatizing, and its effect may have nothing to do with addressing the root drivers of climate forced displacement. The artists recognize that this may have a specific desired impact in the way that individualized stories often do. But they also remind us of the shortcomings of recreating victim/savior dynamics. Why are we telling the story of an individual forced to leave and not the story of the oil company or lobbyists who created the conditions for that displacement? Puck Lo’s aesthetic decisions in (Almost) Freedom, a short documentary film about detained migrants preyed on by a private ankle-monitoring company is one example of how to invert this lens; they decided the protagonist of the film would be the ankle monitor not the person wearing it. What solutions would arise from applying a similar storytelling ethic in art and in law?

But the methods, skills and analysis developed through artistic practice are unique and, like so many movements before, will play a key role in the future of this work.

Or in the case of numerous other projects by the artists in the circle, what happens if you create an infrastructure for democratizing the practice of storytelling? If you shift authorship? How might people use this democratic platform in ways that couldn’t have been imagined at the outset? This was the case with Rachel Falcone and Michael Premo’s project Sandy Storyline. When they created an open-source story platform for people to share stories of the impact of Hurricane Sandy, they had not imagined that it would be used, as it was, in court proceedings for people fighting against evictions after the storm. This principle is embedded in the structure and activities of the Another Gulf is Possible collaborative (of which Jayeesha Dutta is part), a grass-roots, woman-of-color-led group that centers cultural organizing, arts-based healing, direct action, advocacy, transformative justice, education, and locally-led capacity-building training.

While the broader field of artistic work focused on climate forced displacement is still at an early stage of output, our Artist Circle provided insight into a variety of roles that artists can play within.

One helpful theme for thinking about the potential role of artists related to climate forced displacement is that of home. Climate displacement ultimately winds its way back to the question of home, which is something that the artists have extensive experience in making work about. Climate displacement works on this theme at both the level of our specific place-based homes and the larger existential home; planet earth. At the smaller scale of home, the artists raised questions of who we are, memory, relationships, livelihood, safety and opportunity. These questions surface in a time-period that is witness to the largest human migrations ever. At the larger planetary scale, home raises questions about the very livability of humans on Earth.

If the complexity of this issue is confounding for legal experts, politicians, researchers and organizers, there is similarly not a single role that artists can inhabit. Rather, in our discussions on the issue, our own work and the work of other artists, different approaches specific to artistic practice emerged as relevant to the complexity of this issue. Their varied impacts were not necessarily planned ahead of time, but emerged through the skillfulness and contingencies of their work. The goal of categorizing these impacts and effects here is to reflect the unique roles and skills that artists bring to this issue. This can help funders, artists, organizations and interested partners think about how resources, opportunities and connections can more precisely be made available for artists.

The goal of categorizing these impacts and effects here is to reflect the unique roles and skills that artists bring to this issue. This can help funders, artists, organizations and interested partners think about how resources, opportunities and connections can more precisely be made available for artists.

Within the Artist Circle discussions, we never settled on a single frame for understanding climate forced displacement. Perhaps this is the privilege of artistic inquiry, but it also reflects the ways that analysis of the issue shifts and changes based on local context and the boundaries of one’s perspective. In presenting their film After/Life on the intersection of U.S. military rehearsal theaters in the US desert and migrants crossing that same landscape by foot, Puck Lo compelled us to think about militarization and border security in both propelling the climate crisis and acting as a xenophobic and nationalist solution to climate forced-migration. Alia Farid’s catalyst project about interspecies communication between herders and buffalo in the war-trampled marshes of Southern Iraq raises questions about the broader relationships of place, livelihood and culture that are erased during displacement. In discussing Molly Crabapple’s collaboration with Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, we are reminded of the potential in futurist thinking to compel new action today. And in discussing climate displacement in Northern Africa with Hamza Hamouchene we were reminded that a longer tail of historical analysis reframes climate displacement as one of the lasting effects of European colonialism and the inheritance of a post-colonial development/progress mindset. Each of these examples - a reflection of the unique inquiry processes of artists - open our frame of analysis in important ways, shading at radical opportunities for change and helping us to not stumble into false solutions.

Thinking through the different levels of home presents an opportunity and a reminder of the necessity to bridge across issues, places and scales. We know that climate displacement is a global issue, with no one safe from its potential impacts. But we also cannot erase the differences in drivers, impacts and opportunities to recover or adapt that exist in different places and within places. By connecting textured stories across place and home, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of root drivers and opportunities for action. This translocal approach requires authentic and nuanced stories, not archetypes and stereotypes. It also requires creating the infrastructure for sharing stories across places. Lizania Cruz’s project We the News does this in large part through the tool of the story circle, creating opportunities for Black immigrants and first-generation Black Americans to tell their different stories in a shared space. Cruz’s mobile newsstand becomes the opportunity for a public resharing of these stories, both complicating identity and experience, and creating opportunities for a broader analysis and political identity. Cruz buttresses the potential for action out of these stories through her partnership with the Black Alliance for Just Immigration. Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi’s catalyst project for the Artist Circle will involve screening his new film We Still Here/Nos Tenemos in communities dealing with climate displacement. The outreach strategy for the film builds on his experience with another initiative (Cine Solar Rodante) he conceptualized with Defend Puerto Rico; a mobile, solar-powered cinema that screened films across the island in the months after Hurricane Maria when there was no power. Jacobs-Fantauzzi and Dutta also collaborated to bring Cine Solar to Gulf Coast communities. Each of these efforts reflects the nimble and skillful way that artists create opportunities for bridging points through careful storytelling and democratized, autonomous platforms for engagement.

There is, and will continue to be a massive need for healing, to address the trauma, grief and loss caused by climate forced displacement. As a multiplier of existing poverty, instability, and violence, climate forced displacement further disconnects people from place, community and resources that can be essential for a sense of self, relationality and cultural sovereignty that are foundations for healing practices. This may include access to medicinal plants, food sources that maintain traditions, gathering spaces for religious, spiritual or ritual practices or even the ‘weak-tie’ connections (acquaintances) of routine day-to-day life that are a highly protective health factor. Within the metaphorical clearcutting caused by climate disruption and displacement, artists frequently are the first to repopulate the forest and bring new life. In some places, people are going so far as to call artists “first responders.” Cine Solar Rodante is one example of this (mentioned above). Popping up immediately in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, Sandy Storyline created an open source infrastructure for people to document their own stories (they are archiving this project as part of their work in the Artist Circle). Importantly, this work was closely tied to mutual aid efforts that sprang up in communities where city government and Red Cross were inadequate, slow or unwilling to respond. And out of her years of experience in organizing and art-making around the climate crisis in the Gulf Coast, Dutta is now moving towards addressing the question of healing head on through the establishment of a bath house and arts center. She reminds us of the need to care for ourselves and each other in doing this work both for sustainability and as a praxis of creating the world we want to be in. Similarly, her catalyst project centers on a day of community arts based healing for Gulf South residents directly impacted by climate displacement.

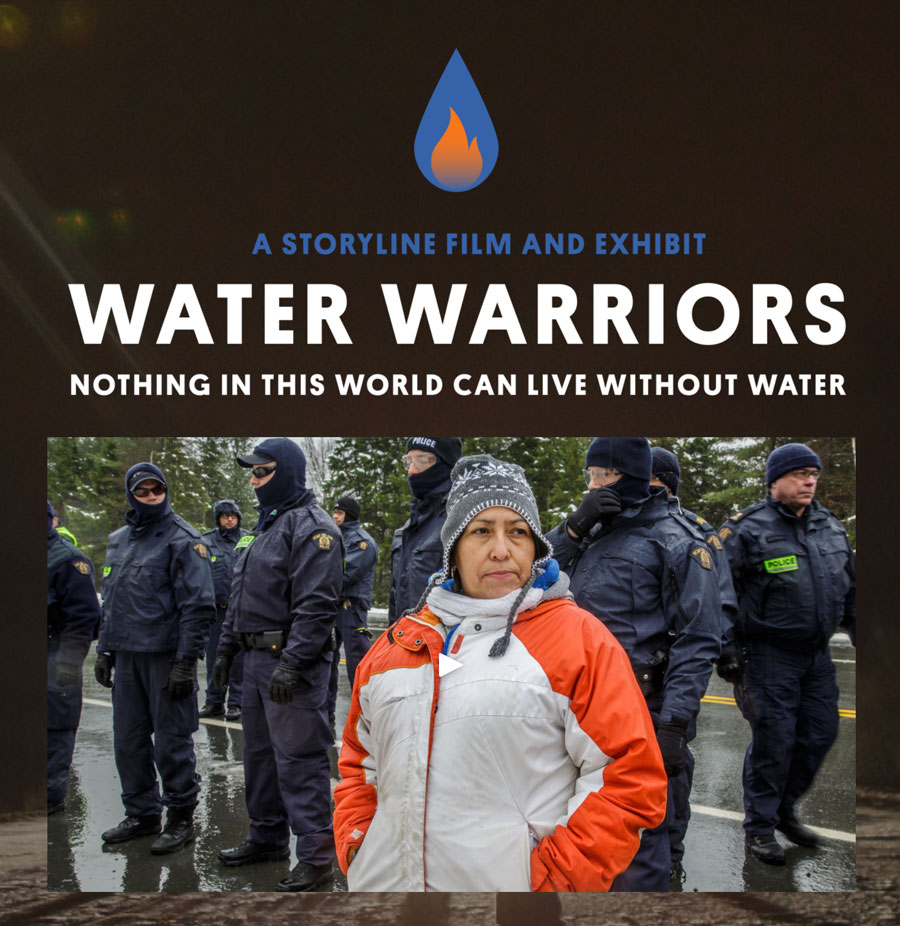

The majority of artists we chose to work with engage in explicit partnerships and collaborations with organizing groups and broader movements. As the climate crisis and displacement is very much a live issue, the artists have found ways their work can contribute to power-building and strategy sharing. Jacobs-Fantauzzi refers to his documentary practice as “living documentary,” a reflexive approach that recognizes that the making of the film plays a part in shaping the story it is telling. His inclusion of his own laughter or exclamations from behind the camera, participation in direct action, and training people who are “subjects” in the film to use cameras to shape the films (and create their own work) reflect this practice he has honed over many projects. Another project by Falcone and Premo, Water Warriors, demonstrates the longer tail that artists work can have in building power and strategy sharing. Their decision to make a short (23 min) film that visualized blockade strategies of fracking companies, reflected a diverse and unlikely coalition and was shot almost entirely from the perspective of people at the frontlines of the protest (including cell phone footage), giving an urgency and concreteness to the actions of the water protectors. The film, which predates Standing Rock, has continued to find resonance within Native and First Nations water protectors and is shown in school settings in the region. Finally, the series of short films Paradises of the Earth, produced by guest speaker Hamza Hamouchene is a direct documentation of translocal power-building. The series of four short films (directed by Nadir Bouhmouch) follow a solidarity caravan of activists from North Africa who visit four locations in southern Tunisia dealing with the environmental impacts of extractive development and different forms of organizing and resistance to this extraction. As Bouhmouch has written, the films reflect the principle that, “We refuse to wait to tell our stories. We will tell them now.” And within this telling the films capture nuanced discussions that took place on buses, beaches and offices about the conflicts between labor and environment, the future and the present, collective and individual that will be central to any future efforts to address the climate crisis in Tunisia and North Africa. These films document and amplify the understanding that, as Robin D.G. Kelley has written, “Social movements generate new knowledge, new theories, new questions.” 1

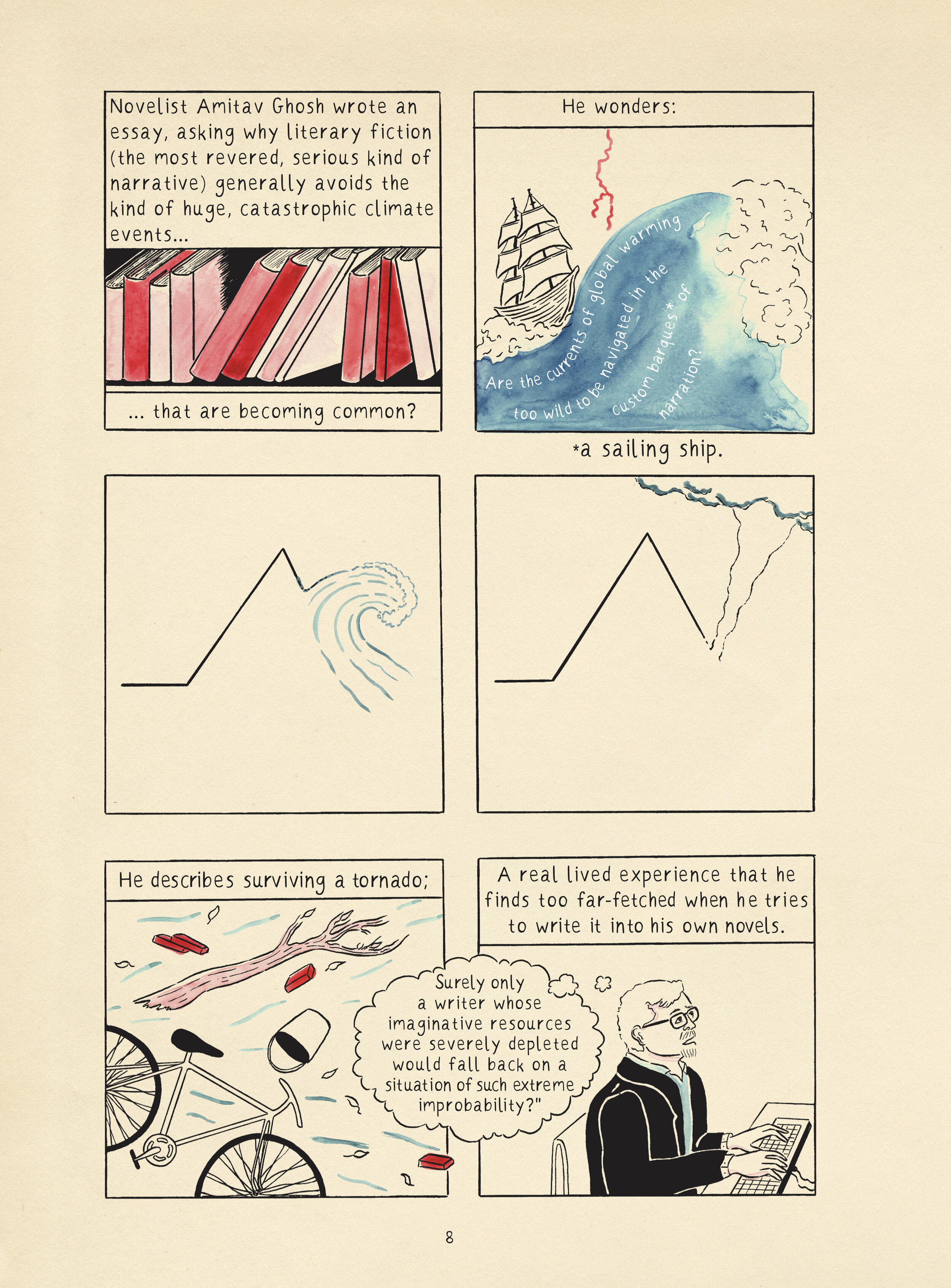

The climate crisis has provoked an unanswerable anxiety about the future of human life on earth. Climate displacement further exacerbates this anxiety. This doesn’t fit particularly well with the dominant story form in the United States (and by hegemonic extension, much of the world). Generally, even with cataclysmic war, the dominant story form moves from conflict to resolution. There is some type of progress, no matter the horror. This type of “linear progress” thinking shapes not only dominant stories, but as anthropologist Anna Tsing points out, in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World, it also shapes dominant approaches to science, economics and history. But what if there is no resolution? What if the conflict continues to unfold in an increasing chain of intensity (as it has with fire season in California) instead of acting as a singular event in history? The artists in the Circle were already consciously disrupting the traditional “progress” story form, recognizing its limitations derived from a Western theological tradition and reliance on the hero myth. Alia Farid’s non-linear films documenting ritual practices in Iraq and Lo’s non-humans as the protagonists of films are examples of this. Lo explores this further in their essay on making art in the apocalypse, questioning the depth to which the limits of our ability to tell varied types of stories challenges our ability to respond to the climate crisis, relying instead on main characters like Elon Musk or Tony Stark. The essay comes back to a simple and powerful conclusion, that requires us to re-engage our technologies of noticing what is, our relationships to what is around us and living into this rather than a nostalgia for purity or resolution. The artist's ability to find beauty amidst a constantly changing and violent world might just be the skill we need to radically engage the present. These works remind us of the urgent need to disrupt this dominant story way of thinking, which constrains our imagination and limits our actions. Pulling lessons from the prison abolition movement, Robin D.G. Kelley expands on this point, “we on the Left are saddled by a theological tradition of prefiguation that imagines a liberated future as the fulfillment of a radical practice. My great friend Ruth Wilson Gilmore knows better; for her, abolition is not the end of history, but life in rehearsal, rich with lessons and contingencies.”2. Artists play a central role in building this muscle, not only through what stories are told, but also how they are told.

In thinking through the Artist Circle, the coordinators (Mina and Evan) often discussed and drew inspiration from comparative movements where art and culture sparked broader public shifts towards expanded belonging. One that we often thought through is the dramatic shift in narratives about and by incarcerated people and the broader understanding of the prison industrial complex. Decades of creative and cultural output (alongside organizing, journalism and more) about the prison industrial complex have complicated public understanding of incarcerated people and the many factors that have led to such an expansion of mass incarceration in the U.S. Perhaps most importantly, this has created a common sense about the systemic racism that undergirds prisons and policing in the U.S. This has created the space for numerous, if also at times imperfect, reforms. In broad strokes, these efforts moved the organizing and advocacy away from individualized responses that relied on the reformed or cleaned up individual (although these still exist). One example policy that was quickly copycatted around the country is “ban the box”, which prevents asking about prior conviction before offering someone a job. This created a blanket protection for a larger group of impacted people rather than leaving the individual to ‘prove’ themself. In large part, this was possible because of a commonplace understanding of the injustice and impacts of incarceration; the many barriers to employment once convicted, the disproportionate way that people of color and poor people are incarcerated and how those barriers contribute to return to incarceration. This more complex understanding of incarceration and its shift of the acceptability of systemic reforms (vs individualized ones) could provide a useful template for how artists and storytellers might seed a climate of belonging for the treatment of the climate displaced.

As the undeniability of climate displacement grows, more and more work will be made about it. But what kind of work? Will it seed more fear (even unintentionally) or help us to transform society? It is our responsibility at this stage to carefully reflect and learn from the skills and methods of experienced artists who can guide how we tell stories and what stories we tell about climate displacement - from the streets to courtrooms, from government to the UN.

1 - Robin DG Kelley. Freedom dreams: The black radical imagination. (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2002).

2 - Elleza Kelley, Robin D.G. Kelley, "Imagining the Immeasurable," Deem: Envisioning Equity, no. 3 (2021); 59.