Still from "Water Warriors", Storyline

The terms we use about the intersection between climate catastrophe and displacement has been of constant discussion in the Artist Circle. Overall, available terms feel inadequate in addressing the complexity of this issue, which ultimately finds its roots in the legacies of colonialism and capitalism. We also saw how important terms are for framing different understandings of root causes, driving legal, political and economic action, and signaling the othering and belonging of groups.

Many of the terms surrounding this issue require subjective interpretation and analysis. We relate to them differently. We may have different intentions for them that we have neither the time nor the capacity to fully communicate. This can have unintended consequences of which we must be aware. This doesn’t even begin to address the questions of translation for a global issue.

We began this project building on research from the Othering & Belonging Institute about climate refugees. In our Circle discussions, we quickly pinpointed the ways in which the term “refugee” can be victimizing and individualizing, how it can be used to stir up xenophobic — particularly racist — reactionary policy, and how it can shift our analysis away from an individual’s “right to stay.” On the other hand, we were reminded by Yumna Kamel of Earth Refuge (the first legal think tank dedicated to climate displacement) that ‘climate refugee’ is both a legal strategy and a term that can push its way upstream to impact larger structures. “Refugee” status requires a named persecutor. By extension, if “climate refugee” becomes a legal tool within the UN framework, it requires us to name and identify accountable parties - governments and transnational corporations who have, so far, not been held accountable for their environmental destruction.

The discussion around the term ‘refugee’ demonstrated that there are different spheres of language where terms gain, lose or shift value and meaning. We have to be reflexive and transparent about which spheres we inhabit when we use these terms and how terms change in meaning when they are used across these various spheres. Our discussions have touched on at least four spheres of language. There is an intellectual sphere that seeks to capture nuance and complexity. There is a policy and legal sphere that works within its own logic system and strategy. There is a popular or cultural sphere related to the way we understand these issues in the context of our respective lived experiences and worldviews. There is also a poetic sphere, which may prove to be essential in cultivating the energy, imagination and sustainability to address this subject.

Perhaps most of all, we were reminded of the need for humility in communication. Things change. Terms shift. New language is constantly invented or discarded. Being curious about the way we use words and where they’ll be useful is a dynamic and essential part of this work. As a result, the set of key terms below is not meant to be comprehensive or definitive. Instead, it is meant to be transparent, a reflection of our sustained dialogue with these concepts, strategic uses of them and their surrounding contexts.

Why Refugee is a legal status that affords protection for people in some countries under the UN Refugee charter of 1951. As of 2022, there is no international refugee status for people who have had to move due to climate events; only for political or identity-based persecution. Refugee is also a loaded term that is deployed on one hand as a scare-mongering tactic and on the other as a sympathy tactic. Typically these revolve around a racialized and stereotyped image.

Who doesn’t use itSome people who have had to move due to climate events, some organizers and researchers.

Why As a legal status, it doesn’t exist and is technically incorrect. It also holds a lot of symbolic baggage and is seen as victimizing and easily used to stir up xenophobic responses.

Who uses it Legal advocates, some people who have had to move due to climate events, newsmedia, politicians

Who uses it Journalists, centrist policy advocates or politicians.

Why Situates movement of people across and within borders as a natural process without naming root drivers. Can be read as acknowledging the agency of those who are moving.

Who doesn’t use it Organizers, polarized politicians.

Why Doesn’t name or focus on root drivers and powers that contribute to this movement. “Naturalizes” the process of migration within a human-induced event.

Who uses it Advocates, organizers, storytellers, directly impacted people.

Why Indicates that someone has been forced to move against their will, with climate as the primary cause. Shows directionality and acknowledges people’s desire to stay. Calls up other movements and emotional connections to other forms of displacement as related to inequality and injustice.

Who doesn’t use it Directly impacted people, centrist politicians, some scholars or journalists.

Why Indicates potential of perpetrators and therefore potentially more politically contentious. May not capture people’s description of why they have moved (ex. In North Africa people generally see the reasons as economic or political, even if they are closely tied to climate impacts). May not align with people’s analysis of climate change as a root cause of displacement.

WHY IT'S USED Names responsible parties in the establishment of a refugee case (currently under UN convention, definable only via identity or political persecution) or lawsuit.

Why it's not used So far, corporations have not been identified as persecutors as related to refugee status despite documented lobbying and intervention in political processes. There remains a lack of public consensus around who is responsible (due in part to extensive lobbying and communications strategies) for which impacts and because climate events often happen within a chain, they make it harder to pinpoint who exactly is responsible.

Global Elite Global ruling class (government and corporate) that drives and profits from the economic system accelerating the climate crisis. Not necessarily aligned in politics, geography or stance on climate crisis. Often in competition with one another (ex. US and Chinese geopolitical interests in East Africa).

COLONIAL ELITE Ruling class (government and corporate) that facilitates neocolonial economic relations between global elite and post-colonial nations. The role of colonial elites was discussed in our look at just transition efforts in North Africa and the way that development has substituted for colonialism, while still benefiting the very few.

OTHERING describes the process of designating a social group as ‘the other’. Nature itself is also othered through its modern or post-European Enlightenment categorization and definition in opposition to humans. This othering creates the foundation for extraction, domination, erasure and violence. This mechanism of group-based marginalization works across a range of differences including race, age, gender, class, disability, sexual orientation, religion and so forth. This fuels the climate crisis through the creation of sacrifice zones and disposable communities. Othering also shapes political responses to climate migrants.

BELONGING is a primary resource distributed in society that stretches from the felt to the structural. Belonging entails the presence of love, power, responsibility, agency and co-creation. This means that belonging is also about process (co-creation) and outcome (co-ownership) in creating the structures and norms to which we belong.

Michael Premo reminded us that the phrase ‘climate change’ was pushed by a conservative strategist in the second Bush administration to make what is happening with our planet seem slower and less consequential than it really is (the memo in full emphasizes emotion and story in particular). The Othering & Belonging Institute prefers to use the term climate crisis instead. Others prefer catastrophe for its immediacy, while some share that we are already overwhelmed with the largeness of this issue without calling it a catastrophe. Fossil fuel companies have recently mounted a narrative campaign that isn’t about denying climate change, but instead showing that they are engaged in social justice related to climate change (“greenwashing”). This is a way to slow calls to action and minimize the scale of response needed. It also reflects the way that language can be manipulated to establish credibility and commitment.

Within the circle, we struggled with the term migration because it leaves so much out of the conversation. It doesn’t address history (including histories of forced migration via the reservation system or enslavement of African and African-descended people), root causes, or power dynamics. It also describes phenomena in the natural world that occur among non-human species. For example, after watching a film by Alia Farid, we had a lengthy conversation about the way that a specific ritual dance has moved along migration routes that stretch between West Africa, the Arabian Gulf and the Americas. Some of this “migration” was trade-based, some of it religious, and some of it was through forced bondage. Migration as a term doesn’t capture this complexity, even as this example revolves around the evolution of a linked cultural practice. As Michael Premo shared, if the term migration was a painting, it would feel like a part of the composition is just missing. Puck Lo offered the term displacement instead, which resonates and connects to other popular organizing and narrative struggles around housing and home. Rachel Falcone reflected on how this frequently connotes something that has already happened, in the past tense. As a frame for mobilizing support for people’s ability to stay in place and address the climate crisis, in this way it seems like starting with your weight on your heels.

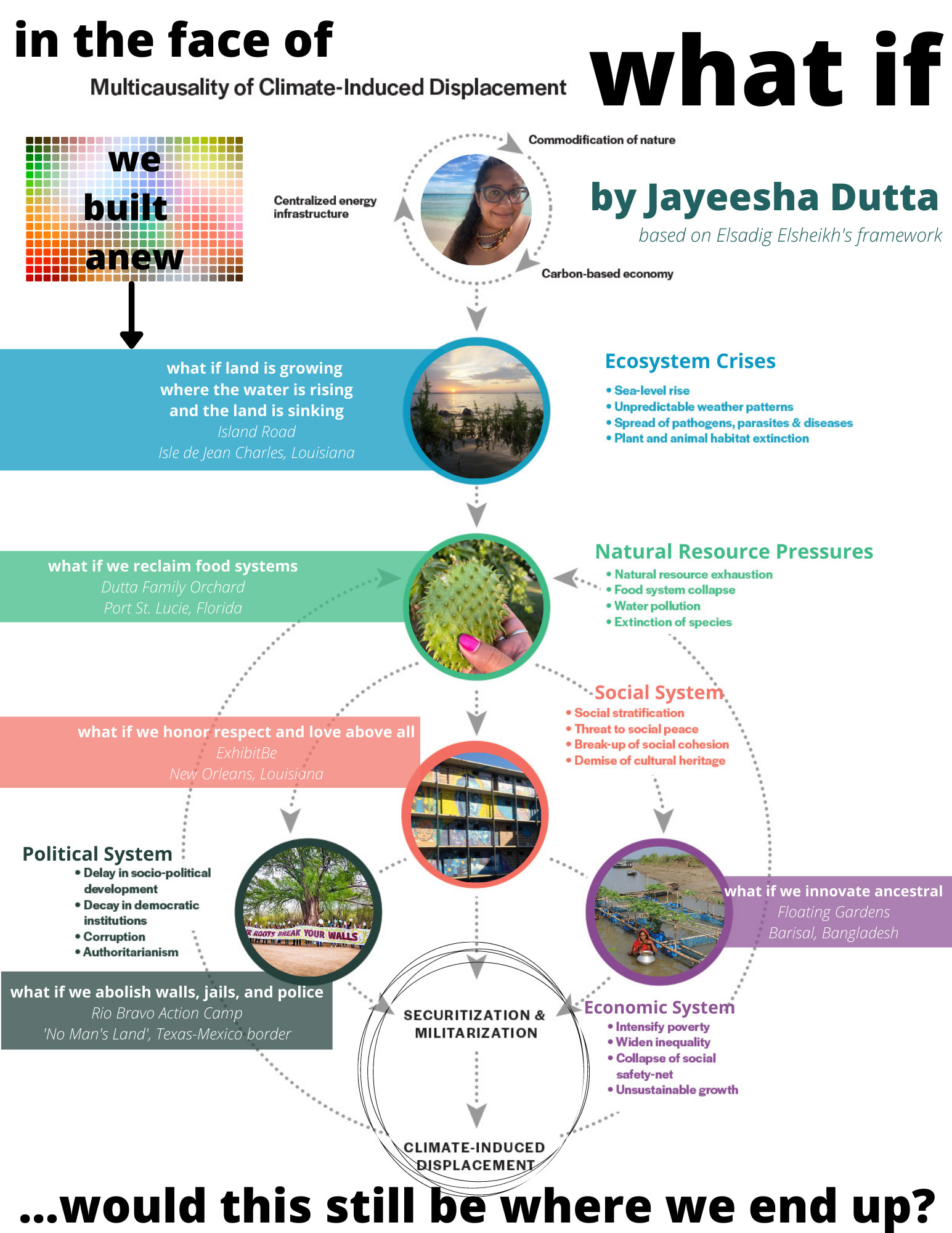

This is meant to pinpoint the way that climate plays a role - direct (forced) and indirect (induced) - in the increasing movement of people within and across national borders. For example, the Syrian political instability resulting in an atrocious civil war is now understood by many to have been in part induced by environmental injustices exacerbated by an extended drought. The diagram1 explores the ways in which the climate crisis generates displacement. You’ll notice in the diagram that the starting point (Climate Crisis) is surrounded by existing forces that lead to this crisis: the commodification of nature, a carbon-based economy and centralized energy infrastructure. (You can check out Jayeesha Dutta’s adaptation of this diagram, charting her personal and family story here).

Climate Displacement reminds us of the different spheres where language holds power and meaning. Climate-induced or Climate-forced Displacement captures the complexity of the issue, but loses punch. In our conversations we mostly used this term for shorthand while acknowledging that it captures a wide suite of drivers including long-term drought, overheating, new bugs/pests in farms, and coral death, as well as acute drivers like hurricanes or fires. But in other conversations around this issue where there wasn’t time to build shared understanding, Climate Displacement more frequently brought to mind the acute forms of displacement that have been making headlines - particularly storms and fires.

In his presentation to the Circle, Hamza Hamouchene acknowledged climate as a multiplier. But aside from a few direct and acute cases, Hamza was hesitant to claim the climate crisis as the actual cause of displacement in the North African context where he works. The phrase isn’t as resonant because people first identify economics (poverty) and political repression as reasons why they have migrated. Climate is intimately tied to these of course - the destruction of small scale farms and industry causing movement to cities with minimal economic opportunity, or the political power and repression required to protect mining interests of European companies. But the destruction of the environment which has precipitated the climate crisis has its roots in colonialism and capitalism. In this regard, calling it “climate-induced displacement” actually obscures the deeper root cause of extractive economics and the legacy of colonialism. He also cautioned that it potentially sets the stage for solutions rooted in “eco-facism” that address the climate crisis but not the vast power and economic inequalities that facilitate unmitigated extraction.

As our collective awareness of the disastrous impacts of the climate crisis grows, individuals, governments and companies are compelled to respond with sustainable, renewable and adaptive activities. Increasingly - and especially within the context of migration - many of these actions are formed through ‘eco-fascist’ frameworks that rely on various forms of othering such as nationalism. These efforts seek to put up border walls, blame pollution and climate change on other countries and people or hoard resources needed for sustainability and adaptation efforts. Thought distinct, at times, we connected this strategy to a different but related tactic; greenwashing. In this case, national or corporate actors use sustainable and “eco” efforts to “greenwash” other forms of repression, displacement or exploitation, making them appear more conscientious and progressive. These efforts frequently rely on the othering of people who bear the brunt of this impact - Palestinians whose lands are seized for nature preserves or low-wage Amazon workers who will soon stock an all-electric delivery fleet.

In his presentation to the Circle, Global Justice Program Director Elsadig Elsheikh raised the right to stay as a key element in addressing the climate crisis. For many of us versed in displacement work - from Palestine to the Bronx - the idea resonated immediately with movements for the Right of Return. The right to stay also raises important questions about othering and sacrifice zones. Who has already been deemed as having to go? Who is deemed still worthy of adaptation efforts to keep them in place? In 2009 at the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, a document was leaked showing that wealthier nations (European and North American) were on the verge of agreeing to a cap at 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. This target essentially acknowledges and accepts the devastation of many countries, especially those in Africa. After the text was leaked, African delegates filled the conference halls shouting, “We will not die quietly!” The Right to Stay raises questions that are essential to thinking through othering and belonging in the context of the climate crisis.

The impact of the climate crisis, who is and who will be forced to move are distributed unevenly across identity - particularly race, class, gender and age. Climate reparations address this inequity in an expansive way, pointing towards “a systemic approach to redistributing resources and changing policies and institutions that have perpetuated harm - rather than a discrete exchange of money or of apologies for past wrongdoings.” At the heart of this work, is the need to address climate displacement. As Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and Beba Cibrlic argue, this means shifting capacity and resources to support place-based mitigation and adaptation strategies (preventing migration) while simultaneously supporting just migration policy that can respond to the millions of people who are and will be displaced.

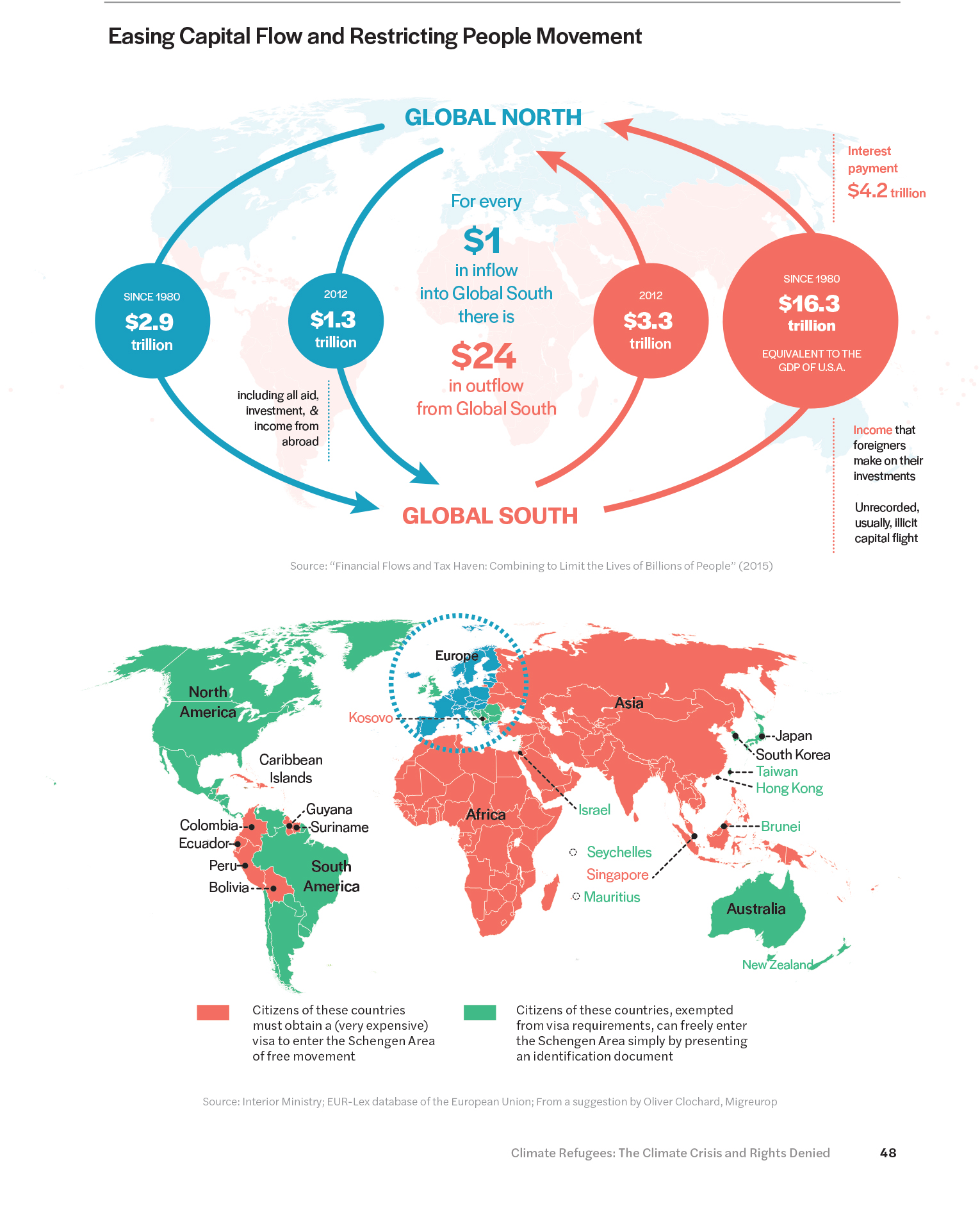

When we talk about the climate crisis, where do we begin the conversation? In the collection of short films Paradises of the Earth, members of the transnational solidarity brigade debate the terms colonialism and development. They point to the lasting impact of colonialism in North Africa and the way that European colonialists have made way for domestic elites who now use the language of development to advance similar agendas of resource extraction (minerals, labor, water, gas, etc). This is further emphasized in the diagram1 shared by Elsheikh Elsheikh, looking at global capital flows from the global south to the global north that continue today.

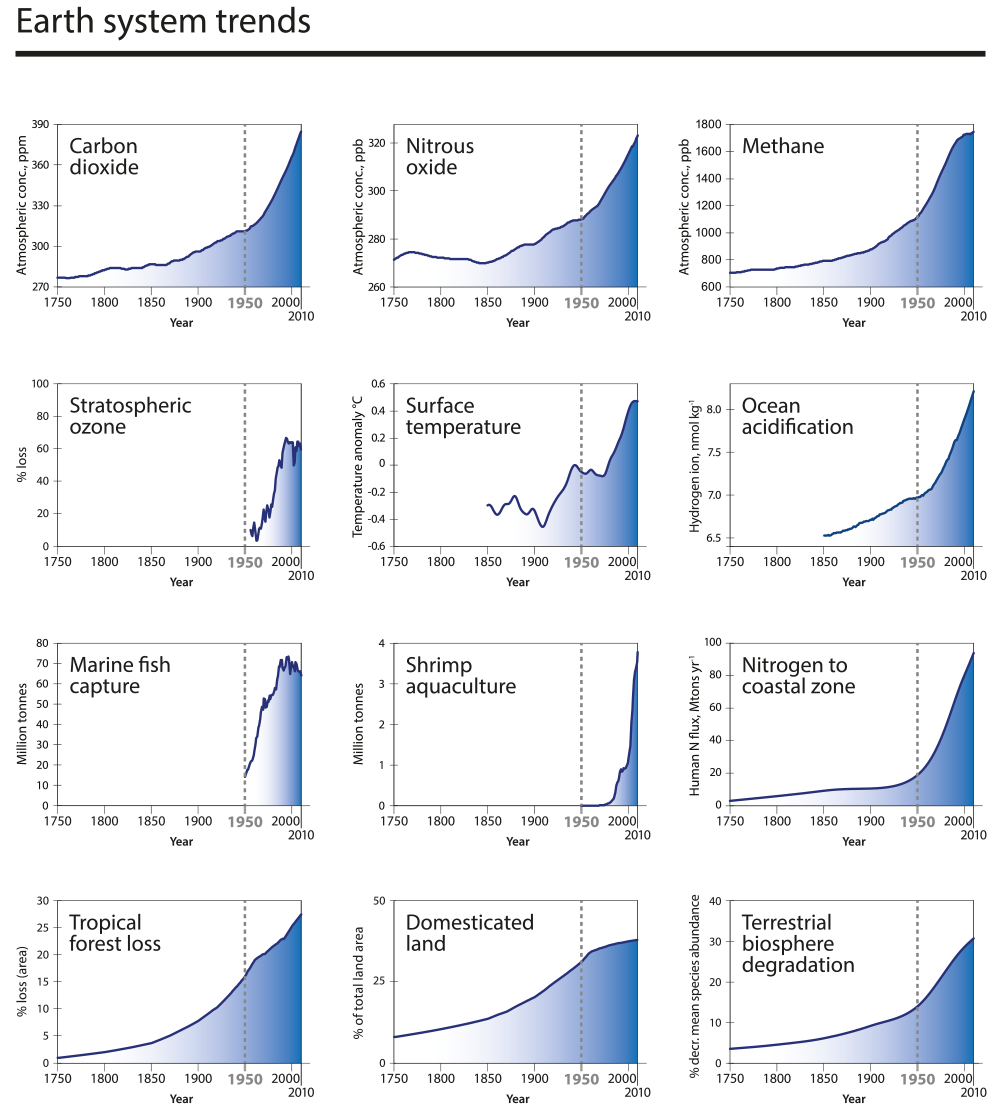

Elsheikh shared how the growth of a global economy post WWII is marked on nearly every earth system trend with a significant rise in the second half of the 20th century (See Diagram2). Using this timeframe as a starting point reflects the urgent acceleration of the climate crisis.

We used these terms generally and without hard boundaries. We framed the Global South as countries that haven’t been the ongoing beneficiaries of colonialism and empire. Those that have been the beneficiaries - such as the U.S., Canada, the UK, the EU countries, Russia, and Japan - were often referred to as the global north. But in both cases, the boundaries are porous and slippery. There are global norths in the global south - both within places and in class and identity divides. There is also an evolving shift in who is deploying capital and political power globally - particularly in the investment activities of China in parts of Africa and South America. These categories were primarily useful as a way to reflect dynamics of power within global economic and military systems, but they frequently lost their usefulness as we moved into deeper and more specific discussion.

Displacement raises the question of rootedness. Within the U.S. housing justice movement, displacement frequently refers to communities pushed out who have lived in a place for 30 to 50 years. There is a degree of rootedness that is a core part of the claim in fighting against this displacement. How does this timeline change within climate displacement? How does this change when we think about neighborhoods (displaced residents of Rockaway due to Hurricane Sandy) compared to when we think about countries (Tuvalu) or forests (the Amazon). How does this change when we also do the necessary work of thinking through forced displacement of Indigenous peoples? What about people and communities who retain a relationship to place that stretches as far as human history? How do we hold this complexity with Indigenous claims to land - not only because Indigenous place-based practices are often sustainable and validated through hundreds, if not thousands, of years of stewardship, but because it reflects a core element of decolonization? In our discussions, the reminder that all lands are Indigenous lands is an essential starting place for reconsidering how we might frame home.

1 - Hossein Ayazi and Elsadig Elsheikh, Climate Refugees: The Climate Crisis and Rights Denied, (Berkeley, CA:Othering & Belonging Institute,University of California Berkeley, December 2019), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/climaterefugees.

2 - Will Steffen, The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration (Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm Resilience Centre and the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, January 2015).