"We the News" Installation image, Lizania Cruz

How do our stories about climate displacement keep up with the rapid acceleration of the issue? We repeatedly confronted the way that existing popular narratives (particularly those that circulate in the Global North) rely on stereotypical understandings of refugees, a simplified understanding of the climate crisis, and both explicit and implicit nationalism. This section documents our acknowledgement that some of these myths and realities are dynamic and up for debate depending on one’s framework of analysis or the intended outcome of one’s work.

Most climate forced displacement is internal to national borders. Climate events are one of the major drivers of the 55 million people living as internally displaced people in 2020.

This depends on how you analyze climate displacement - induced, forced, a manifestation of colonialism? Does this only account for fires and hurricanes? Or, for example, does this “total number of displaced” also account for the disruption of ecosystems (ocean acidification, new pests, drought) that previously supported small-scale farming or provoked other forms of violence?

The question of what a border is also depends on where we place the lens of analysis. As Lizania Cruz reminded us, while the movement of people due to the climate crisis might not be a primarily cross-border event, transnational corporations and military forces (a major consumer of fossil fuels) are constantly engaged in cross-border activity. We are also experiencing major migrations across the “border” between the urban and the rural. When we mention cross-border, what types of activity are we tracking?

Climate change by itself is not what causes a permanent move in most cases but acts as a multiplier that makes life untenable for people with limited economic and political power. Climate change must be understood within the context of its interaction with political, socio-cultural, and economic systems and dynamics.

Direct displacement will continue to increase as acute crisis events increase. We have already seen this in the past decade due to the increasing frequency of major storms and fires.

Again, it depends on how wide one draws one’s field of analysis for the root drivers of displacement. What do we gain by naming climate change as the root cause? What do we gain by naming capitalism or colonialism or white supremacy and patriarchy as root causes? One idea is that in order to create alternative systems that work, we must know what elements of our current ones we must dismantle. In order to do that, we must understand how current systems have led to the crisis we call climate change.

What do we gain by naming climate change as the root cause? What do we gain by naming capitalism or colonialism or white supremacy and patriarchy as root causes?

While we don’t have conclusive surveys about whether people prefer to stay or move, we do have powerful poetry and examples of people organizing to stay, developing adaptation strategies and lobbying global actors who are responsible for displacement through the creation of sacrifice zones in multi-national climate agreements. Additionally, we know that many people move back to their homes after acute crises have resolved in order to rebuild and reroot. We continually returned to the discussion of the “Right to Stay” as an important organizing frame for addressing climate displacement - especially as people who live in or come from places acutely threatened by climate crisis - Puerto Rico, Kuwait, and the Gulf Coast among many others.

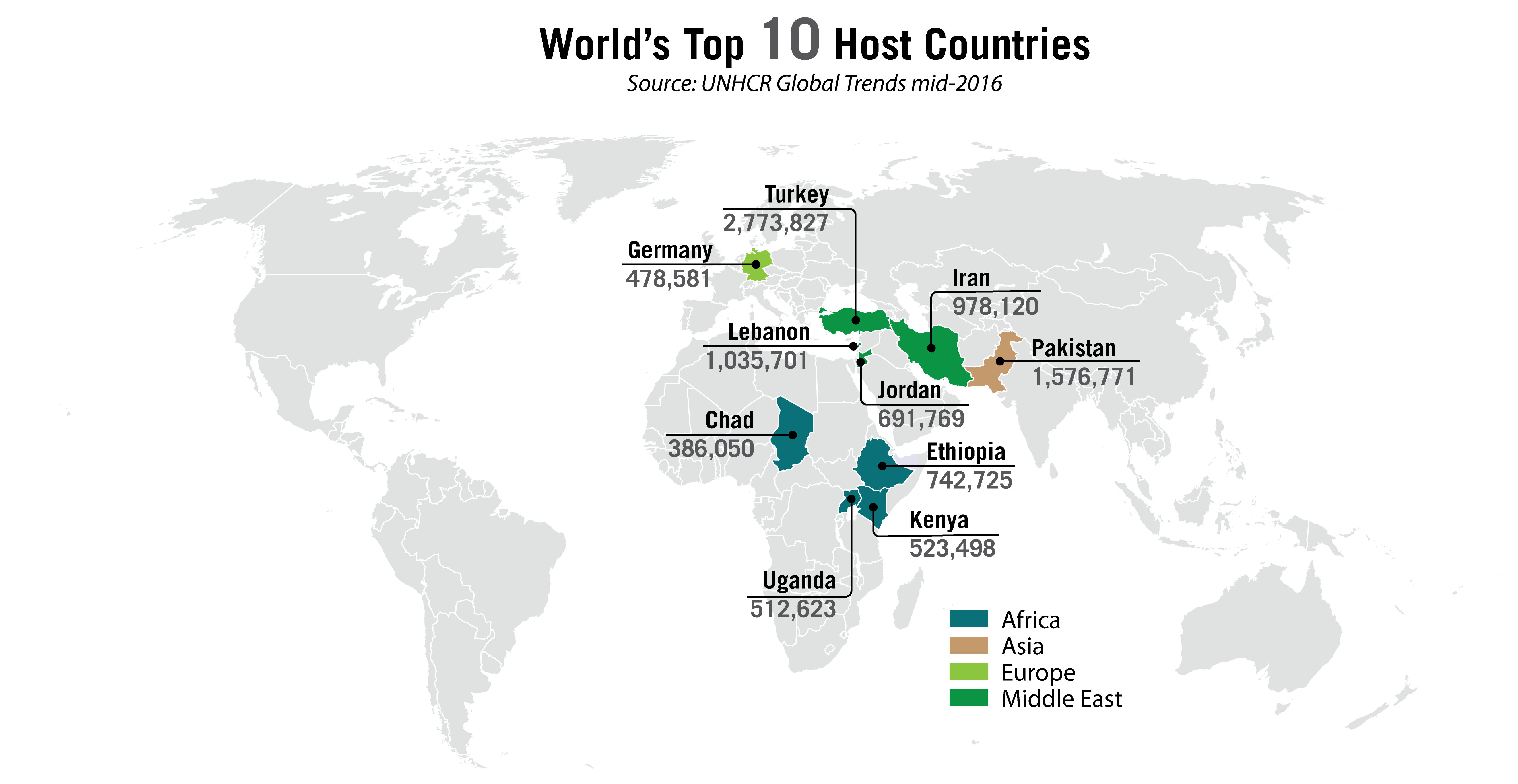

As noted before, most climate displacement happens internally within national borders. In addition, the countries hosting the most displaced people - both in total number of displaced and as a percentage of their domestic population - are overwhelmingly in the Global South (as shown by chart1 below). In part, this is due to the huge investment in border securitization in countries of the Global North and the multiple challenges of cross-border movement that make this type of migration possible. For example, the United States’ long standing collection of policies that fall under the umbrella of ‘prevention through deterrence’ increase the danger of migration by funneling people crossing the southern border through the deadly Sonoran desert.

Despite a general consistency in power relationships, historical colonialism between the global north and the global south has shifted towards a more complex global relationship based in international development (see the short docs we watched Paradises on Earth for a discussion on the language of colonialism and development). More countries and domestic elites are driving capitalist, carbon-based growth models of expansion that rely on rapid resource extraction and burning of fossil fuels. Some of these are home-grown, but many are driven by Global North investments in new markets and the expansion of political and military influence. Despite this shift, the US remains the largest historical contributor to global warming.

Governments - particularly the huge investment in and resource consumption of military and police forces - have contributed immensely to and underwritten the climate crisis. There has been much written about the relationship between governments, militaries, police forces and the expansion of corporate power under the framework of neoliberalism. In many ways, global securitization (the ability to use the threat of military response to quell rebellion, migration or community autonomy) is a precondition of climate chaos disparities, the creation of sacrifice zones and the extraction of resources. While the level of changes we need will require massive government action, we must also be able to hold the complexity of knowing that many of these same actors are responsible.

One of the questions that has been extremely generative for us is the question, “what metaphor do you use to understand where we are in relation to the climate crisis?” The responses reflect the incredibly different ways that people create a self-understanding of where we stand currently. Within our group the metaphor ranged from dying to a Phoenix, falling off a table after sliding along it to chronic illness, midwives birthing something new to the end of humans but a new phase for the planet. By using metaphor we are able to create a bit of distance from the idea of crisis or catastrophe and understand in more nuance what our underlying hope and vision is for the actions we take.

We have reached a point where climate change has saturated public conscience and a majority of US citizens acknowledge it. But we are still split on how we address climate change as shown by this study: Nearly two in three Republicans believe oil and gas companies are at least somewhat responsible for the climate crisis – but only 1 in 3 think the government should do more to make these companies accountable.

By using metaphor we are able to create a bit of distance from the idea of crisis or catastrophe and understand in more nuance what our underlying hope and vision is for the actions we take.

No single story is perfect, nor do all stories move across contexts perfectly. For example, an incredibly common request of artists and storytellers is to “humanize”. Reflecting on this request to “humanize” people prompted discussions on the limits of empathy as a viable and inclusive strategy that addresses structural change. Too often this narrative strategy finds manifestations in policy that hinge on bad/good criminals or the bad/good immigrants. This re-individualizes the issue of climate displacement. Other types of stories that emerged in our discussions include: survival stories that share knowledge and ways of relating that can guide us through climate displacement; uplifting stories that inspire through concrete examples; stories that name bad actors and inspire accountability; and science-fiction stories that allow us to “time-travel” to understand parallel struggles, strategies and radical futures. Rachel Falcone reminded us that this question on the type of story we must tell is not new, the dilemma of whether we focus on the problem, the solution or the struggle to get there pervades storytelling.

An incredibly common request of artists and storytellers is to “humanize”. Reflecting on this request to “humanize” people prompted discussions on the limits of empathy as a viable and inclusive strategy that addresses structural change. Too often this narrative strategy finds manifestations in policy that hinge on bad/good criminals or the bad/good immigrants.

Symbols, images and stories derive their meaning from context. They can be used, reused and remixed. For example, in 2005, the film NEM-NEE was screened for the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva as a way to visually emphasize the hardships of migrants living in Switzerland and advocate for expanded resources and rights. A few years later, the filmmaker learned of a video very similar to NEM-NEE that was being distributed by a “perception management campaign” throughout sub-Saharan Africa as a deterrent for potential migrants. One Swiss newspaper shared the video with the title, “This is how we scare Africans.” 2

Jayeesha Dutta further complicates this myth. Who is using story to ‘create better conditions’? Whose story is being used? And why? In addition to the context of imagery, there is the need for an analysis of questions of power and extraction in our storytelling efforts.

Can they? It seems that storytellers are constantly balancing the questions of scale, impact, practice and truth. As Issy Manley points out in this comic on stories and the climate crisis, the dominant Western story structure generally follows a linear format that ultimately finds resolution. Even the horror of war has been resolved many times in human history. While we may be facing a completely different moment with no exact precedent for resolution, there isn’t anything particularly novel about neverending crisis, as experienced by Indigenous, racialized and poor people. Puck Lo comments,

“It seems like the difference might be scale? Like, we have had Hiroshima, Bhopal, genocides and so much more... but has the entire planet ever experienced multiple crises simultaneously in ways that, while not equal, persist unabated? (Covid + climate change + global rise of fascism?)”

What we know is that confronting the climate crisis in any meaningful way requires urgent action on every front of life, at many scales and potentially in perpetuity. This means that our actions can’t be linear, rely on one protagonist or even project a resolution to the crisis. If stories shape our imaginations on how we respond to this crisis, how can our stories help us imagine new approaches through shifting the form of the story itself? In our circle we frequently discussed the limits of traditional narrative forms - instead looking to crowd-sourced storytelling, non-human “protagonists”, practice-based storytelling, or living documentary. This last term comes from Eli Jacobs-Fantauzzi to describe his filmmaking practice that is aware that it is changing and being changed by the people and the issue it is telling stories about.

There are many ways to define an “artist” and the “products” they make. For many in the group, this includes the relational, fleeting and knowledge-based elements generated through a complex process. As Jayeesha Dutta reminded us, artists are often the historians of the future, holding a vision that inspires in spite of despair, while also holding nuanced practice in building trust, community and relationships through the process, creation and expression of art itself. Puck Lo reminded us that artist disciplines (and what we see as artistic outcomes) are frequently defined by the market, prompting us to think outside of conventional understandings of artists and instead more expansively about what role artists might hold. One thing that resonated with many of us is that art is often the by-product of the processes, relationships and collaborations that we engage in. Therefore it is not just what we make, but the methods, skills and experiences of artists that will be crucially important to addressing multi-sector approaches to climate displacement.

One thing that resonated with many of us is that art is often the by-product of the processes, relationships and collaborations that we engage in. Therefore it is not just what we make, but the methods, skills and experiences of artists that will be crucially important to addressing multi-sector approaches to climate displacement.

In reflecting on apocalypse thinking, Puck Lo raised the limitations of stories that rely on a heroic main character who will revert us back to a right or pure way of things. This type of thinking pervades popular narratives around addressing issues at the scale of climate change. One thing we agreed on in the Circle is that neither artists, politicians nor billionaires can address the climate crisis alone. Artists offer unique skills, methods and products that can greatly aid our collective ability to respond to climate displacement. But it will need to be a collective response. Artists can play an important role, but in order to protect this role, we must also protect their ability to explore, play, experiment, witness, note and dream.

1 - Hossein Ayazi and Elsadig Elsheikh,Climate Refugees: The Climate Crisisand Rights Denied, (Berkeley, CA:Othering & Belonging Institute,University of California Berkeley,December 2019), belonging.berkeley.edu/climaterefugees.

2 - Thomas Keenan, Aspirational and Operational Maps of Migration, in When Home Won't Let you Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art (Boston, MA: The Institute of Contemporary Art in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, January 2020)