Lizania Cruz

Directly across from my grandparents backyard was a large smoke stack that spelled Boca Chica in all caps letters. Boca Chica is the town’s name and the name of the sugar mill founded in 1916 where my grandfather worked as the chief chemist for almost 45 years. Originally owned by the West Indies Sugar Corporation and bought by Rafael Leonidas Trujillo in 1957, it later became part of el Consejo Estatal de la Azúcar (CEA). During zafra, which started each year in the beginning of December and ended in June, black clouds of smoke were continuously expelled from the top of the smoke stack leaving a film of cachispa (soot) everywhere; from our skin to the furniture. It was impossible to keep surfaces clean. This landscape was the backdrop of most of my childhood memories. And la cachispa a texture that I assimilated as part of nature.

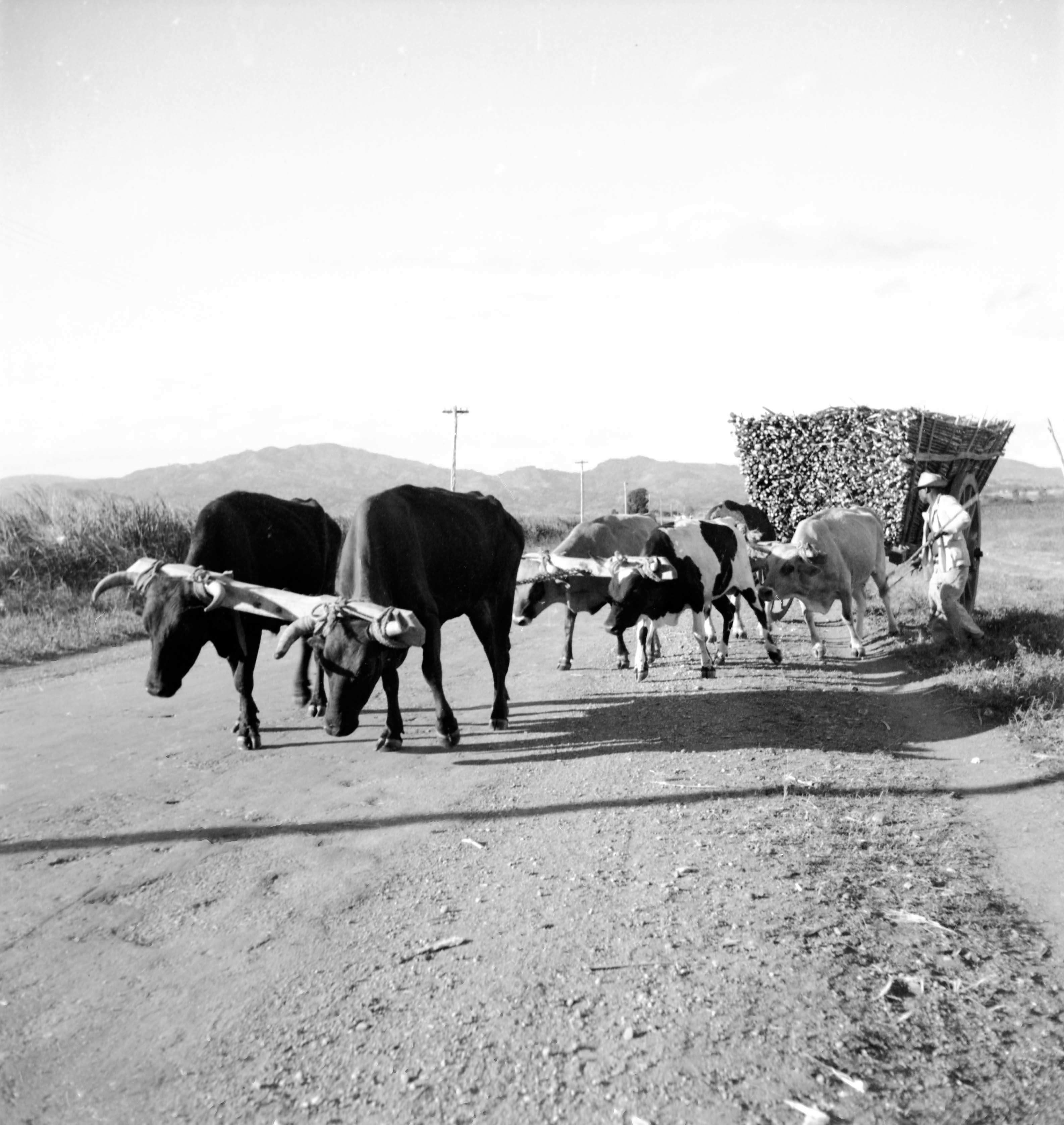

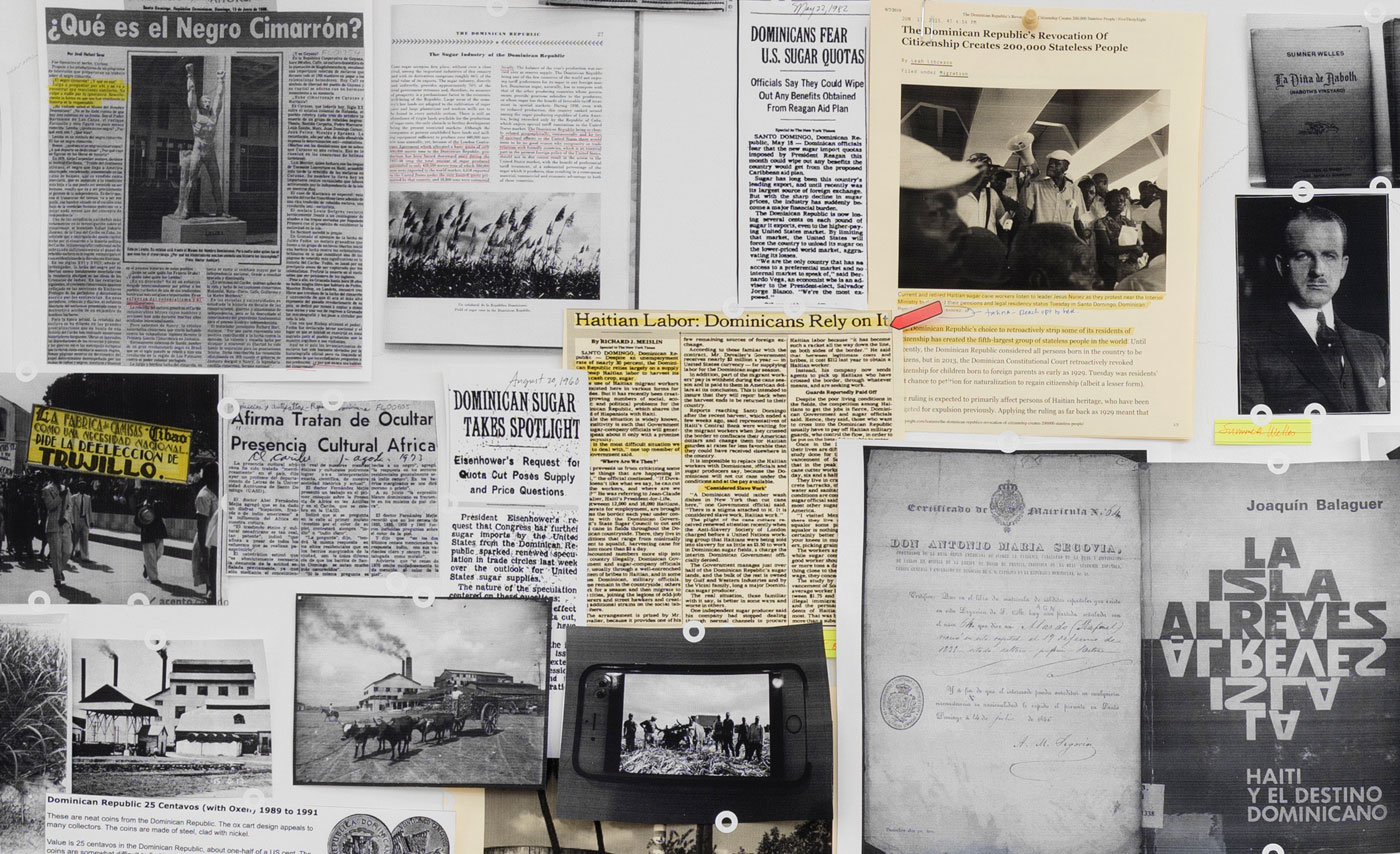

The history of sugar cane in the Dominican Republic is the history of colonization. Sugar cane was brought to the island on the second trip of Cristobal Colon from the Canary Islands and planted widely as a monoculture. Since then and during its modern reincarnation as the main export of the country in the 20th century, it has been linked to the economy of exploitation and migration movements. From the Africans whom were brought to the island as enslaved labor, to the cocolos from the Anglophone Caribbean islands who migrated to cut sugar cane, to the Haitian braceros and undocumented workers who sustain the industry since its hay days to today. The industry's main profit came from the exports of its production primarily to the United States.

Today the lasting effects of this colonial industry are visible in the daily human rights violations on its workers as well as in the change of the ecosystem in the island. The mills that are still in operation like Central Romana Corp., have been accused of human rights violations from poor workers' pay to clandestine evictions. As reported by the Washington Post on the Pandora Papers “Workers for Central Romana say they earn around $125 a month cutting sugar cane, well below the country’s average monthly salary of $777, according to the latest figures from the Central Bank of the Dominican Republic. Most are migrants from Haiti, and few have the rights of full citizenship.”

Depriving sugar cane cutters in the present day through low wages isn’t even enough. The Dominican government decided to reach into the past as well. In 2013 the state passed La Sentencia 168-13. A law that retroactively stripped Dominican nationality of an estimated 250,000 Dominicans of Haitian descent leaving them stateless. Most of the people affected by this law are the descendants of the workers who came to cut sugar cane for mills such as Central Romana and Boca Chica. Furthermore the plantation of sugar as a monoculture has had lasting effects on the land's biodiversity and its nutrients. This cycle causes pests and other harmful insects to propagate, often pushing farmers to use harmful chemicals for both the people and the land to control them. As an example, in 2017 the sugar mill owned by Grupo Vicini was accused of using pesticides such as glifosato killing crops and livestock of local farmers to protect their sugar plantations.

With this in mind, I've been reflecting on the plantationocene and its effects on racial constructs and the land today. The plantationocene has been described as the epoch that highlights the planetary effects of extractive practices, monoculture development, and exploitative labor drawing attention to the legacy of colonialism and its racial hierarchies. I’m reminded of Donna Haraway's words “The plantation disrupts the generation times of all the players. It radically simplifies the number of players and sets up situations for the vast proliferation of some and the removal of others.”

This is one of the reasons why sugar is the central motive in my work Investigation of the Dominican Racial Imaginary. This criminal investigation, which is a participatory and research based art project, looks at how the nation-state has repressed and erased the African heritage in the Dominican identity and how it continues to racialize some bodies for profit. In conjunction with this, I’ve been considering how the law also acts as a system that reinforces who belongs and who doesn’t, by labeling some people as “illegal” and denying refuge. If it is at all possible for it to serve as a tool for justice when we have seen it fail us for so many years. And as scholar Jacqueline Battalora states “white supremacy has been embedded in the United States of America since its funding as a matter of law”. So then, what strategies can we utilize to collectively gain power within this system?

The Dominican Republic remains one of the world’s top suppliers of sugar to the United States. Which begs us to look closer at the implications of the global north in the economy of extraction of the global south, its continued exploitation of labor through racialization, and the tax heavens that are created for the private companies that benefit from this exchange. To an extent allowing the capitalist system of exchange and exploitative labor to remain unchecked.

Today only the ruins of the smokestack of the Boca Chica mill stand. La cachispa is no longer in the air but its black toxic powdery texture can still be sensed in the environment and in the lungs of those of us who were close to this industry. Especially those who dedicated their lives as labor and are still waiting to receive their pensions. As I travel back to photograph what is left of the infrastructure I find myself wondering— what will justice look like for this community and the land that has been greatly altered to sustain it.