Alia Farid

Evan Bissell: Can you give us a bit of context on Chibayish. What is its history - long and short term? Who lives there? What are they facing today in terms of being pushed out? Why did you go there?

Alia Farid: There is a group of marshes in southern Iraq where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers meet. One of them is called Chibayish. It is where I was filming in November. When people think of the Arab world, they often think of a barren, lifeless place even though southern Iraq was once home to 32 million date palms and waterways around which the city of Basra was built. My grandmother on my father’s side is from Basra. My father grew up spending weekends there at a time when the border was not as rigid as it is today. After the 1990 Gulf War, moving across the border (a border that was created by colonial powers and that created tensions over resources) was no longer easy.

There are a few reasons why I’m interested in this region: it relates to my own family history; it is part of a group of works that I have been developing that probes the impact of extractive industries on the land and social fabric of southern Iraq and Kuwait; the destruction of the southern marshes of Iraq and the flattening of 22 of 32 million palm trees in Basra is an ecological crisis that is overlooked and has been eclipsed by 40 years of war (war that is the result of interest in the resources of this land, but that is depicted by western media as self inflicted).

Iraq: Dissident Areas From Iraq a Map Folio, CIA, 1992 (170K)

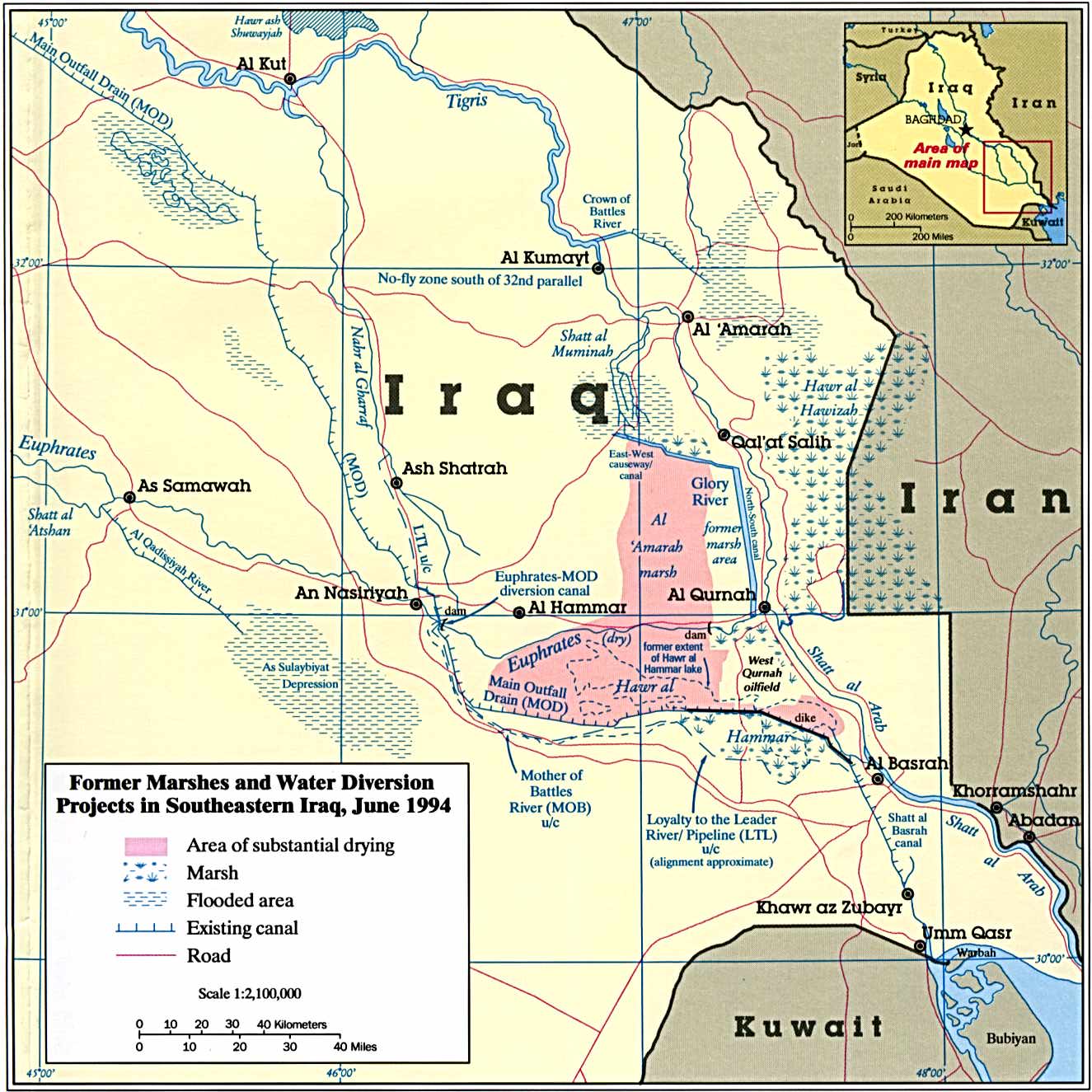

Iraq - Marshes - Former Marshes and Water Diversion Projects in Southeastern Iraq From The Destruction of Iraq's Southern Marshes, CIA Publication IA 94-10020, 1994 (243K)

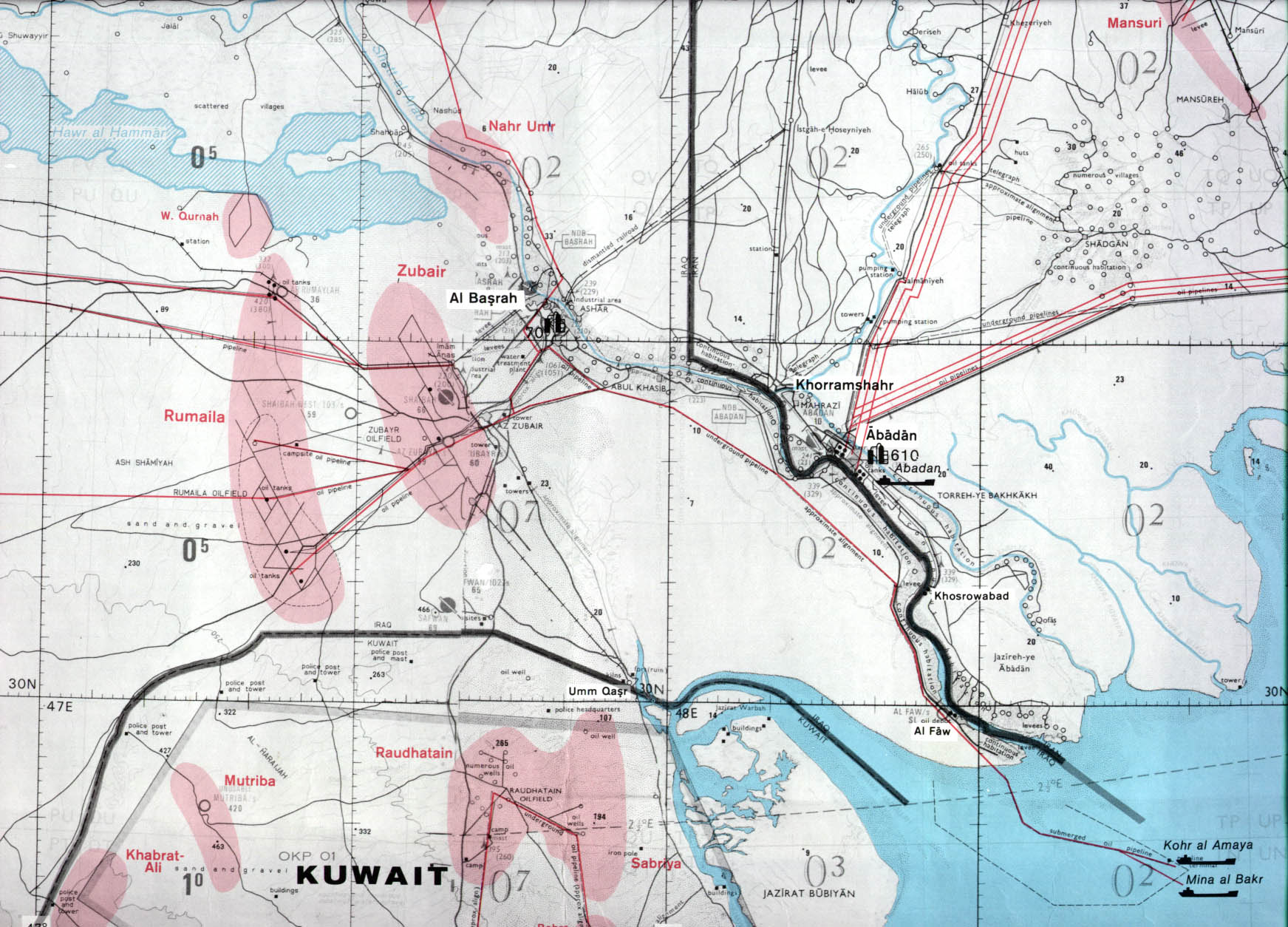

Al Basrah Region - Oil and Gas Fields original scale 1:670,000 From Iraq-Iran: Central and Southern Border Areas CIA 1980 (400K)

EB: Can you share reflections about the relationship between culture, place and interspecies/ecosystem relationships from your work in Chibayish? How has this changed in the face of climate catastrophe?

AF: While filming in the southern marshes of Iraq, I heard how the marsh residents call their buffalo back from the water. The marsh inhabitants live on islands made of compacted clay and reeds, and on these islands they build and live in reed houses. Attached to each of the houses is an area where their buffalo stay when they are not in the water. This was the first time I heard a buffalo call, which is a combination of Arabic, low, short guttural sounds, and song. And suddenly buffalos began to appear from every side, through the water. And they, the buffalo, respond as they make their way back. I was very moved by the calls, which I perceive as an interspecies language. The buffalos in the southern marshes do not wear harnesses, bells, ears tags, or any branding. They roam freely. And their relationship to the marsh residents is a reciprocal relationship whereby both buffalo and human understand that their livelihood depends on each other.

It is like Vandana Shiva writes, “When we live with deep recognition of interconnectedness, we nurture those relationships. Non-separation and interconnectedness is the nature of reality. What appears different is actually different expressions of an interconnected reality.”

EB: Interspecies communication, which you will focus on for the Catalyst project, could to some seem “bizarre” or even “exotic” or “esoteric”. On the surface, it also doesn’t seem to relate to climate displacement. In documenting this in Chibyish, what are you reflecting about its value in the world? How does this intersect with climate displacement? About the ability and importance of staying in place in the face of war, oil extraction and water struggles?

AF: When we think about drivers of displacement, we mostly think of the eviction and evacuation of people. The most common reasons for migrating are war, contamination, drought, and harvest failure. All of these things are interconnected and have an impact on *all* of the earth’s constituents. It was the 1980s Iraq-Iran war that led to the draining of the southern marshlands and the destruction of 22 million date palm trees in Basra. The draining of the marshes was the largest *engineered* crime against nature of the 20th century. Not only did it force many people out of the marshes, but also other marsh residents, which affected the area's biodiversity. Birds’ migratory routes changed and water buffalos were moved to arid land. Climate displacement affects all species, it affects our interrelatedness. The result is fragmentation, displacement and estrangement.

EB: What role do you play as an artist? Are you documenting this? Are you archiving it? Making a statement? Or something else?

AF: The role of my work is to offer another view, in this case, on the southern marshlands of Iraq. I have been speaking with the anthropologist Birdget Guarasci for nearly 2 years about this subject. She has been collecting data on the number of news stories that use "Eden" or "Sumeria" in their reporting about Iraq's marshes since 2001 and is looking at how major news outlets have reported the Iraqi marshes story in virtually the same way - as an untouched Eden. This effort to complicate the narrative and offer a different perspective on an area whose history and present has been oversimplified, is something I identify with but from an artist perspective.

Interested in learning more? This video has more from Alia on her work in southern Iraq and the region.