Click to download a PDF of this report.

This report is published by the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. The Institute engages in innovative research and strategic narrative work that attempts to reframe the public discourse from a dominant narrative of control and fear towards one that recognizes the humanity of all people, cares for the earth, and celebrates our inherent interconnectedness.

The report was submitted on October 1, 2019 to the United Nations Human Rights Council in regards to the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the United States of America, 36th Session.

This publication is part of the Global Justice Program’s Human Rights Agenda report series. In this series, we collaborate with other human rights, civil rights, and civil society organizations under the umbrella of the US Human Rights Network (USHRN) to advance the utility of the rights-based framework as a meaningful organizing tool for impacted communities and social movements to articulate claims of social, cultural, and political rights, and belonging. Our reports are reviewed by the United Nations Human Rights Commission, and the Human Rights Council, and inform the UN’s recommendations to hold the US Government and legislative bodies accountable to their obligations as related to the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), the International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

I. SUMMARY:

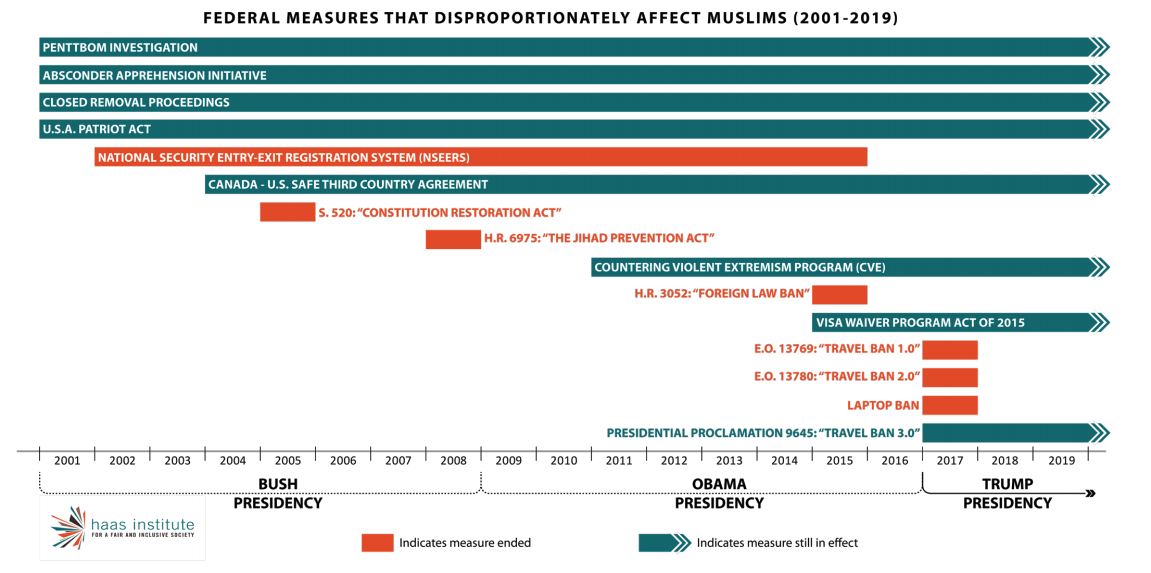

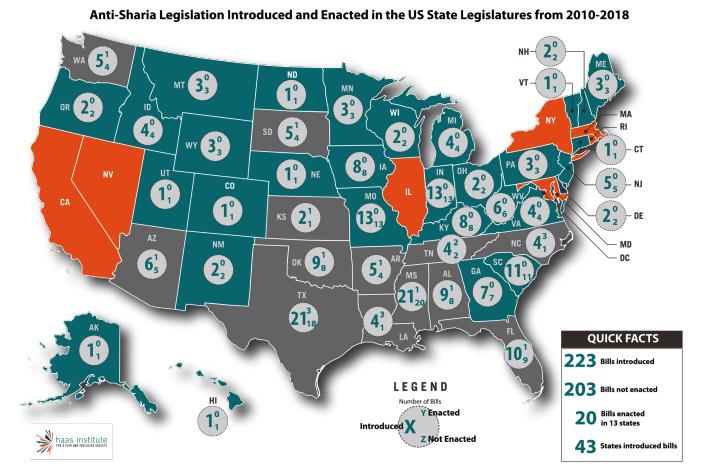

1. For nearly two decades, and spanning three presidencies, the US federal government and state governments have infringed on the freedoms of its citizens and lawful residents by systematically institutionalizing federal measures and state legislation that disproportionately discriminate against, and other Muslims. Since 2001, 15 federal measures* were implemented that target and discriminate against Muslim individuals and communities, the most recent of which is President Donald Trump’s Travel Ban. These measures subject Muslims to unwarranted surveillance, profiling, exclusion, and discrimination along the lines of race, ethnicity, national origin, and religion.Islamophobia is recognized as a form of xenophobia and discrimination based on religious and national origin that aims to single out, exploit, and exclude Muslims. This belief forms the basis of a distorted ideology that views Muslims and Islam as inferior to Judaism and Christianity, as well as a threat to “Western” civilization. Furthermore, since 2010, 223 anti-Sharia bills have been introduced in state legislatures across the US.“Islamophobia,” Othering & Belonging Institute, 2018, accessed Sept. 19, 2019. Among those introduced, 20 bills have been enacted into law in 13 states. These bills impose legal barriers that specifically seek to prevent Muslims from engaging fully and freely with their religion by preventing Islamic interpretations that guide ethical and moral life, as outlined in Sharia, from being considered in US state courts, and by infringing on the rights of Muslims to enter into contracts based on Sharia.Elsadig Elsheikh, Basima Sisemore, and Natalia Ramirez Lee, Legalizing Othering: The United States of Islamophobia (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2017).

2. These federal measures and state legislation are preventing the US from maintaining its obligations to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), as well as US ratified international treaties, notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

* Of the 15 federal measures, 7 are no longer in effect. For a comprehensive timeline of the measures and their status see the infographic “Federal Measures that Disproportionately Affect Muslims (2001 – 2019).”

3. Presidential Proclamation 9645, known as the Travel Ban or otherwise referred to by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and others as the Muslim Ban,“Coalition Letter Requesting Muslim Ban Hearings in 116th Congress,” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed Jan. 10, 2019. is the latest addition to the list of 15 federal measures which effectively enable discrimination against Muslims.Rhonda Itaoui and Basima Sisemore, “Trump’s travel ban is just one of many US policies that legalize discrimination against Muslims,” The Conversation, Jan. 29, 2018, accessed Jan. 5, 2019. The Travel Ban clearly demonstratesThe current version of the Travel Ban, which varies from the previous executive orders in regards to the list of banned countries and the immigrant and non-immigrant visa restrictions for those countries, indefinitely restricts travel to the United States for nationals of seven countries: Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. “Timeline of the Muslim Ban,” American Civil Liberties Union – Washington, accessed Jan. 7, 2019. the US government’s violation of its international human rights obligations, as the ban disproportionality discriminates against Muslims“U.S. Supreme Court Ruling On Muslim Ban 3.0 What You Need to Know,” Advancing Justice-Asian Law Caucus and CAIR California, June 26, 2018. on the basis of race, religion, and national origin.The Muslim Ban: Discriminatory Impacts and Lack of Accountability, Center for Constitutional Rights, Jan. 14, 2019.

4. The numerous iterations of the Travel Ban have made longstanding US immigration laws invalid by creating unwarranted chaos and obstacles for US citizens and lawful permanent residents (LPRs or Green Card holders) to reunite with family members.Window Dressing the Muslim Ban: Reports of Waivers and Mass Denials from Yemeni-American Families Stuck in Limbo (New Haven, CT: Center for Constitutional Rights and the Rule of Law Clinic at Yale Law School, 2018), 8, accessed Jan. 6, 2019. The Travel Ban restricts more than access and ability to travel, as it puts in jeopardy the rights and privileges afforded to US citizens and LPRs by indefinitely separating families, forcing family members to await reunification in conflict zones or other precarious situations where health, education, and economic stability are compromised.Ibid. Furthermore, the ban circumvents US immigration law, which forbids discriminatory practices, such as nationality-based discrimination, when considering the issuance of immigrant visas.Ibid.

5. Still, one of the most evident markers of increased Islamophobia is the rise of anti-Sharia legislation in US state legislatures, demonstrating that discriminatory, anti-Muslim sentiment and policy is not limited to the US federal government. Since 2010 there have been 223 anti-Sharia bills introduced in 43 state legislatures.The Othering & Belonging Institute updates the anti-Muslim legislation database in January of each year, and the data cited for this submission is reflective of data collected up until December 2018. Of the 223 bills introduced, 20 bills have been enacted into law. In addition to stoking an unwarranted fear of Islam and Muslims, the impacts of the anti-Sharia legislation strip Muslims of their legal rights afforded to them by the US Constitution’s First Amendment, as these laws prevent state court judges from considering Sharia and other foreign laws in their proceedings and rulings.Abed Awad, “The True Story of Sharia in American Courts,” The Nation, June 14, 2012, accessed Jan. 7, 2019 The anti-Sharia laws are not only intolerant of those who practice the Islamic faith, but harm all Americans who engage in family matters that involve foreign law, such as in cases of international marriages and adoptions. The unintended consequences of these laws also undermine the ability of courts to interpret laws and treaties regarding global business and international human rights.“Oppose – HB 419: The Anti-Sharia Law Bill,” The American Civil Liberties Union – Idaho, Jan. 31, 2018, accessed Jan. 10, 2019.

II. US NEGLIGENCE IN REGARDS TO ITS INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS:

6. The US government, by enacting and institutionalizing measures that disproportionality discriminate against Muslims, has undermined its own obligations under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, specifically Article 2 and Article 18. Additionally, anti-Muslim state legislation also undermine the civil and constitutional rights of Muslims in the United States and compromise the US government’s compliance with the ICERD, notably Article 2, ¶1(c), and Article 5 (d)(vii), as well as the ICCPR, particularly in regards to Articles: 2(1), 18(1), 23(1), 26, and 27.

7. While there are no recommendations from the 2015 Universal Periodic Review that directly address the Travel Ban or anti-Sharia legislation, this submission references selected recommendations as related to freedom of religion and freedom from discrimination, as these freedoms and rights are subverted by the US government’s implementation of preemptive national security and counterterrorism efforts, which continue to justify policies that violate the civil liberties and rights of its citizens and lawful residents who adhere to Islam. The recommendations from the 2015 Universal Periodic Review include:

a) 176.108 That a mechanism be established at the federal level to ensure comprehensive and coordinated compliance with international human rights instruments at the federal, local and state levels (Norway).UPR of United States of America (2nd Cycle – 22nd session), Thematic list of recommendations, 2015, 11.

US response: Supported a part of the recommendation relating to the coordination of international human rights instruments at the federal level, but did not support the ask to create a single mechanism that would apply to the state and local levels.Ibid.

b) 176.126 Abolish any discriminatory measures that target Muslims and Arabs at airports (Egypt).Ibid., 20.

US response: Supported a part of the recommendation to prohibit measures that discriminate against Muslims and Arabs at airports, and rejected the implication that measures were in place at US airports that target or discriminate against Muslims.Ibid.

c) 176.120 Strengthen the existing laws and legislation in order to combat different forms of discrimination, racism and hatred (Lebanon).Ibid., 21.

US response: Supported a part of the recommendation to combat discrimination, but did not support parts of the recommendation that the US believed would restrict constitutionally protected beliefs or expression.Ibid.

d) 176.132 Toughen its efforts to prevent religion and hate crimes as it is evident that the crimes are on the increase (Nigeria).Ibid., 23.

US response: Supported the recommendation to strengthen efforts to prevent and punish hate crimes motivated by religious hatred, but rejected assertion that hate crimes are on the rise in the US.Ibid.

e) 176.142 Address discrimination, racial profiling by the authorities, Islamophobia and religious intolerance by reviewing all laws and practices that violate the rights of minority groups, with a view to amending them (Malaysia).Ibid., 40

US response: Supported the recommendation to address discrimination and racial profiling by authorities, but did not support parts of the recommendation that the US believed would restrict constitutionally-protected beliefs or expression.Ibid.

f) 176.160 Take steps to eradicate discrimination and intolerance against any ethnic, racial or religious group and ensure equal opportunity for their economic, social and security rights (Turkey).Ibid., 63.

US response: Supported the recommendation.Ibid.

g) 176.131 Continue to take strong actions, including appropriate judicial measures, to counter all forms of discrimination and hate crimes, in particular those based on religion and ethnicity (Singapore).Ibid.

US response: Supported the recommendation.Ibid.

h) 176.149 Combat racial profiling and Islamophobia on a non-discriminatory basis applicable to all religious groups (Pakistan).Ibid.

US response: Supported the recommendation.Ibid.

8. Since 2015, the US government has not only failed to adequately address the above-mentioned recommendations, but has implemented federal measures as well as sanctioned state policies that directly institutionalize and foment Islamophobia and intolerance toward Muslims. As of 2017, three versions of the Travel Ban have been introduced, and on June 26, 2018, the US Supreme Court upheld Presidential Proclamation 9645—the third version of the ban—in a 5-4 ruling in the case Trump v. Hawaii. The Travel Ban has received widespread international criticism, including by a number of UN human rights experts.“US travel ban: ‘New policy breaches Washington’s human rights obligations’ – UN experts,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Feb. 1, 2017, accessed Jan. 10, 2019. In the most recent round of hearings, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the Supreme Court’s ruling on the ban, stating that “the Proclamation was motivated by hostility and animus toward the Muslim faith” and went on to highlight that the Travel ban “now masquerades behind a façade of national-security concerns.”Harold Hongju Koh, “Symposium: Trump v. Hawaii—Korematsu’s ghost and national-security masquerades,” Supreme Court of the United States Blog, June 28, 2018, accessed Jan. 7, 2019 In her sharp dissent,Catie Edmondson, “Sonia Sotomayor Delivers Sharp Dissent in Travel Ban Case,” The New York Times, June 26, 2018, accessed Jan. 7 2019. Justice Sotomayor drew parallels between the Trump v. Hawaii decision and the case of Korematsu v. United States, “Facts and Case Summary—Korematsu v U.S.,” United States Courts, accessed Jan. 7, 2019. the notorious ruling that upheld the forced internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.“The Muslim Bans,” Bridge: A Georgetown University Initiative, Sept. 9, 2019.

9. In a case which drew international criticism and attention to the nature and effects of the Travel Ban and the visa waiver process, the Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) filed a lawsuit in 2018 on behalf of Shaima Swileh, a Yemeni woman who sued the Trump administration to enter the US to be reunited with her husband and two-year-old son, Abdallah Hassan, who was receiving medical treatment in the country for a terminal genetic brain disorder. She was granted a visa following the emergency federal lawsuit and arrived to the US only days before her son’s death.“Yemeni mother wins visa fight to see dying son in US, lawyer says,” AlJazeera, Dec. 18, 2019, accessed April 26, 2019. Swileh’s lawsuit documented how the US government, via the US embassy in Cairo, ignored over 28 pleas and attempts for help regarding her request for a visa waiver.Ibid.

10. In April 2019, the UN Human Rights Committee, in their “List of issues prior to submission of the fifth periodic report of the United States of America,” specifically asks the United States government to address the ability of individuals to obtain visas under the Travel Ban, as well as to address the visa-waiver process, which has a rejection rate of 98 percent.“List of issues prior to submission of the fifth periodic report of the United States of America,” Human Rights Committee, April 2, 2019, accessed April 26, 2019. The Committee also requested that the US Government indicate how the Travel Ban is congruous with the nondiscrimination and non-refoulement stipulations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.Ibid.

11. Additionally, from 2015 to 2018, 78 anti-Sharia bills were introduced in state legislatures across the nation, and five of those bills were enacted into law. It has been evidenced that anti-Sharia legislation is doubly fueling Islamophobia and resulting in a negative impact on the US legal system, ultimately transforming the everyday decisions made in US courtrooms by the enactment of such laws.Abed Awad, “The True Story of Sharia in American Courts,” The Nation, June 14, 2012. In one example, just one month after the Kansas state legislature enacted the anti-Sharia bill, Senate Bill 79 in 2012, the law was used as the basis for state refusal to enforce the dowry of Elham Soleimani who would be owed $677,000 as specified in her Islamic marriage contract if she and her husband were to divorce.Faisal Kutty, “Creeping Sharia of Conspicuous Islamophobia?” Columbia Journal of International Affairs, Oct. 28, 2014. The court ruled not to enforce the Islamic contract, as it would have violated the law following the enactment of SB 79, which resulted in Soleimani losing her dowry.Ibid.

12. As noted in the Human Rights Committee’s Concluding Observations from 2014, the Committee observed that the federal government needs to “give greater effect to the Covenant at federal, state, and local levels, taking into account that the obligations under the Covenant are binding on the State party as a whole.”“Concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of the United States of America,” United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Human Rights Committee, Apr. 23, 2014.

III. RECOMMENDATIONS:

13. In order to uphold its constitutional and international commitments to safeguard human rights, the US government must extend and protect human rights of all persons within its jurisdiction, regardless of race, religion, or national origin. To achieve this, the US government must:

a) Protect the rights of Muslim individuals as enshrined in the US Constitution and rule of law, and consider Islamophobia as a form of religious discrimination and discrimination based on national origin.

b) Immediately rescind the Travel Ban, Presidential Proclamation 9645, as the federal measure discriminates on the basis of race, religion, and national origin, and separates families, as well as infringes on the human rights of individuals within and outside of US territory, disproportionately affecting Muslims and Muslim refugees.

c) Establish a visa waiver process for the Travel Ban that is compliant with the ICERD and US immigration law, which forbids discriminatory practices, as well as to reconsider cases that were denied the visa waiver and to expedite visas to qualifying families and individuals.

d) Prevent the enactment of discriminatory anti-Muslim policies by ensuring that the US Constitution, ICERD, and ICCPR are fully implemented at federal, state, and local levels.

e) Rescind anti-Sharia legislation that have been enacted into law and implement policies to prevent anti-Sharia legislation from being reintroduced and enacted as the laws are inherently discriminatory and xenophobic, and infringe on the constitutional rights of Muslims and nonMuslims within US territory, but disproportionately affecting Muslims.

f) Prevent the enactment of discriminatory anti-Muslim policies by establishing a single mechanism to coordinate compliance that would apply at state and local levels.

g) Pass in the US Senate, and sign into law, H.Res.183 of the 116th Congress, which condemns anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim discrimination, and bigotry against minority groups.